Sixty-six years ago on July 16, 1945 the world witnessed the first atomic bomb test. The bomb lit up the sky and scorched the earth at the White Sands Proving Ground over the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico. The test of the implosion-design plutonium device was codenamed Trinity, part of the Manhattan Project.

Sixty-six years ago on July 16, 1945 the world witnessed the first atomic bomb test. The bomb lit up the sky and scorched the earth at the White Sands Proving Ground over the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico. The test of the implosion-design plutonium device was codenamed Trinity, part of the Manhattan Project.

The lead physicist was J. Robert Oppenheimer. He named the atomic test “Trinity” in a conflicted homage to John Donne’s poem, “Holy Sonnet XIV: Batter My Heart, Three-Personed God”:

[div class=attrib]By John Donne:[end-div]

Batter my heart, three-personed God; for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurped town, to another due,

Labor to admit you, but O, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

but is captived, and proves weak or untrue.

yet dearly I love you, and would be loved fain,

But am betrothed unto your enemy.

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again;

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor even chaste, except you ravish me.

Thirty-three years after the Trinity test on July 16, 1978, poet Allen Ginsberg published his nuclear protest poem “Plutonian Ode”, excerpted here:

. . .

Radioactive Nemesis were you there at the beginning

black dumb tongueless unsmelling blast of Disil-

lusion?

I manifest your Baptismal Word after four billion years

I guess your birthday in Earthling Night, I salute your

dreadful presence last majestic as the Gods,

Sabaot, Jehova, Astapheus, Adonaeus, Elohim, Iao,

Ialdabaoth, Aeon from Aeon born ignorant in an

Abyss of Light,

Sophia's reflections glittering thoughtful galaxies, whirl-

pools of starspume silver-thin as hairs of Einstein!

Father Whitman I celebrate a matter that renders Self

oblivion!

Grand Subject that annihilates inky hands & pages'

prayers, old orators' inspired Immortalities,

I begin your chant, openmouthed exhaling into spacious

sky over silent mills at Hanford, Savannah River,

Rocky Flats, Pantex, Burlington, Albuquerque

I yell thru Washington, South Carolina, Colorado,

Texas, Iowa, New Mexico,

Where nuclear reactors creat a new Thing under the

Sun, where Rockwell war-plants fabricate this death

stuff trigger in nitrogen baths,

Hanger-Silas Mason assembles the terrified weapon

secret by ten thousands, & where Manzano Moun-

tain boasts to store

its dreadful decay through two hundred forty millenia

while our Galaxy spirals around its nebulous core.

I enter your secret places with my mind, I speak with

your presence, I roar your Lion Roar with mortal

mouth.

One microgram inspired to one lung, ten pounds of

heavy metal dust adrift slow motion over grey

Alps

the breadth of the planet, how long before your radiance

speeds blight and death to sentient beings?

Enter my body or not I carol my spirit inside you,

Unnaproachable Weight,

O heavy heavy Element awakened I vocalize your con-

sciousness to six worlds

I chant your absolute Vanity. Yeah monster of Anger

birthed in fear O most

Ignorant matter ever created unnatural to Earth! Delusion

of metal empires!

Destroyer of lying Scientists! Devourer of covetous

Generals, Incinerator of Armies & Melter of Wars!

Judgement of judgements, Divine Wind over vengeful

nations, Molester of Presidents, Death-Scandal of

Capital politics! Ah civilizations stupidly indus-

trious!

Canker-Hex on multitudes learned or illiterate! Manu-

factured Spectre of human reason! O solidified

imago of practicioner in Black Arts

I dare your reality, I challenge your very being! I

publish your cause and effect!

I turn the wheel of Mind on your three hundred tons!

Your name enters mankind's ear! I embody your

ultimate powers!

My oratory advances on your vaunted Mystery! This

breath dispels your braggart fears! I sing your

form at last

behind your concrete & iron walls inside your fortress

of rubber & translucent silicon shields in filtered

cabinets and baths of lathe oil,

My voice resounds through robot glove boxes & ignot

cans and echoes in electric vaults inert of atmo-

sphere,

I enter with spirit out loud into your fuel rod drums

underground on soundless thrones and beds of

lead

O density! This weightless anthem trumpets transcendent

through hidden chambers and breaks through

iron doors into the Infernal Room!

Over your dreadful vibration this measured harmony

floats audible, these jubilant tones are honey and

milk and wine-sweet water

Poured on the stone black floor, these syllables are

barley groats I scatter on the Reactor's core,

I call your name with hollow vowels, I psalm your Fate

close by, my breath near deathless ever at your

side

to Spell your destiny, I set this verse prophetic on your

mausoleum walls to seal you up Eternally with

Diamond Truth! O doomed Plutonium.

. . .

As noted in the Barnes and Noble Review:

Biographies of Oppenheimer portray him as a complex, contradicted man, and something of a poet himself. His love of poetry became well known when, in a 1965 interview, he famously claimed that his first reaction to the bomb test was a recollection of a line from the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Linkin Park’s 2010 concept album entitled “A Thousand Suns” captures Oppenheimer himself reciting these lines from Bhagavad-Gita scripture on recollecting Trinity atomic bomb test. He speaks on track 2, “Radiance”.

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Wikipedia / Creative Commons.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]By Massimo Pigliucci at Rationally Speaking:[end-div]

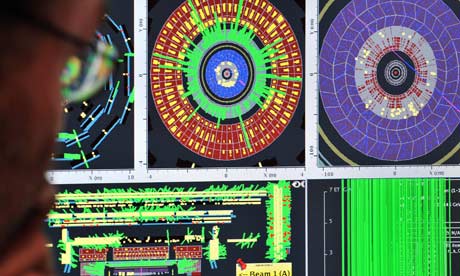

[div class=attrib]By Massimo Pigliucci at Rationally Speaking:[end-div] Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox.

Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox. [div class=attrib]From Ars Technica:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Ars Technica:[end-div] Remember the lowly tourist postcard? Undoubtedly, you will have sent one or two “Wish you where here!” missives to your parents or work colleagues while vacationing in the Caribbean or hiking in Austria. Or, you may still have some in a desk drawer. Remember, those that you never mailed because you had neither time or local currency to purchase a stamp. If not, someone in your extended family surely has a collection of old postcards with strangely saturated and slightly off-kilter colors, chronicling family travels to interesting and not-so-interesting places.

Remember the lowly tourist postcard? Undoubtedly, you will have sent one or two “Wish you where here!” missives to your parents or work colleagues while vacationing in the Caribbean or hiking in Austria. Or, you may still have some in a desk drawer. Remember, those that you never mailed because you had neither time or local currency to purchase a stamp. If not, someone in your extended family surely has a collection of old postcards with strangely saturated and slightly off-kilter colors, chronicling family travels to interesting and not-so-interesting places. [div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

Two exciting races tracked through Grenoble, France this passed week. First, the Tour de France held one of the definitive stages of the 2011 race in Grenoble, the individual time trial. Second, Grenoble hosted the

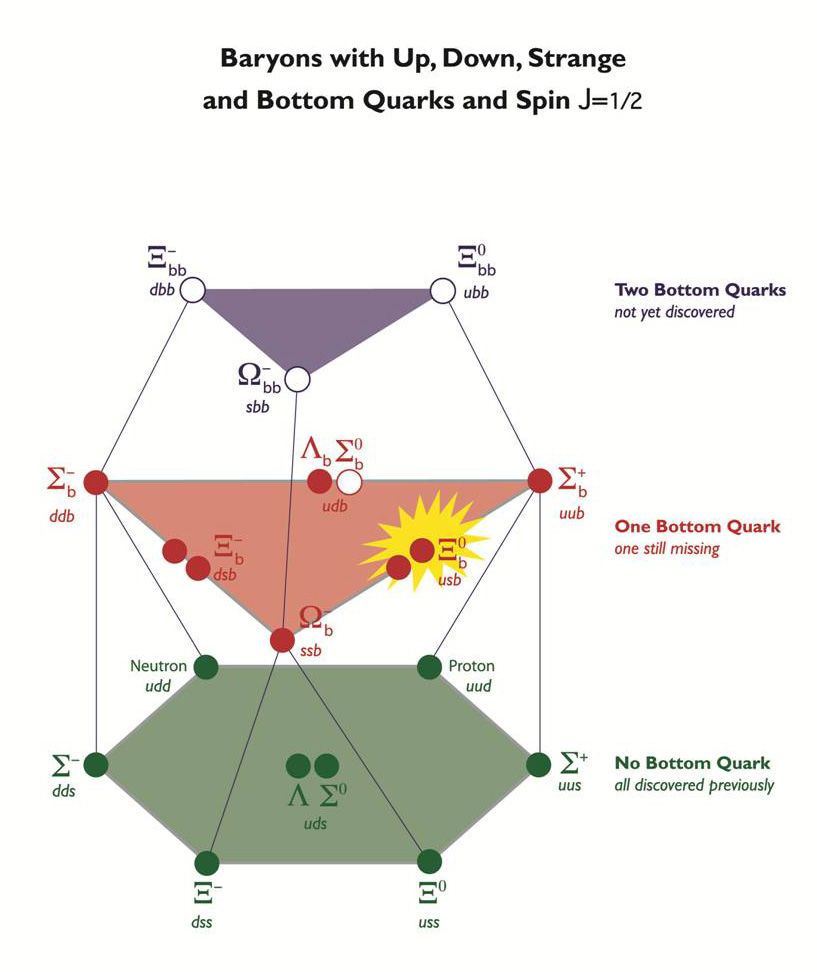

Two exciting races tracked through Grenoble, France this passed week. First, the Tour de France held one of the definitive stages of the 2011 race in Grenoble, the individual time trial. Second, Grenoble hosted the  Both colliders have been smashing particles together in their ongoing quest to refine our understanding of the building blocks of matter, and to determine the existence of the Higgs particle. The Higgs is believed to convey mass to other particles, and remains one of the remaining undiscovered components of the Standard Model of physics.

Both colliders have been smashing particles together in their ongoing quest to refine our understanding of the building blocks of matter, and to determine the existence of the Higgs particle. The Higgs is believed to convey mass to other particles, and remains one of the remaining undiscovered components of the Standard Model of physics. [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div] The lives of 2 technological marvels came to a close this week. First, NASA officially concluded the space shuttle program with the

The lives of 2 technological marvels came to a close this week. First, NASA officially concluded the space shuttle program with the  [div class=attrib]From the Physics arXiv for Technology Review:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Physics arXiv for Technology Review:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div] Phew! Another heartfelt call to action from business blogger Seth Godin to become indispensable.

Phew! Another heartfelt call to action from business blogger Seth Godin to become indispensable. [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div] If you’ve traveled or lived in the UK then you may well have been filmed and recorded by one of Britain’s 4.2 million security cameras (and that’s the count as of 2009). That’s one per every 14 people.

If you’ve traveled or lived in the UK then you may well have been filmed and recorded by one of Britain’s 4.2 million security cameras (and that’s the count as of 2009). That’s one per every 14 people.

Classic dystopian novels from the likes of

Classic dystopian novels from the likes of  [div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Wired:[end-div] The infamous Dead Parrot Sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus continues to resonate several generations removed from its creators. One of the most treasured exchanges, between a shady pet shop owner and prospective customer included two immortal comedic words, “Beautiful plumage”, followed by the equally impressive retort, “The plumage don’t enter into it. It’s stone dead.”

The infamous Dead Parrot Sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus continues to resonate several generations removed from its creators. One of the most treasured exchanges, between a shady pet shop owner and prospective customer included two immortal comedic words, “Beautiful plumage”, followed by the equally impressive retort, “The plumage don’t enter into it. It’s stone dead.”

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq.

A new book by James Morton examines the life and times of cross-dressing burglar, prison-escapee and snitch turned super-detective Eugène-François Vidocq. [div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the New Scientist:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From Institute of Physics:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Institute of Physics:[end-div] [div class=attrib]Bjørn Lomborg for Project Syndicate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Bjørn Lomborg for Project Syndicate:[end-div]