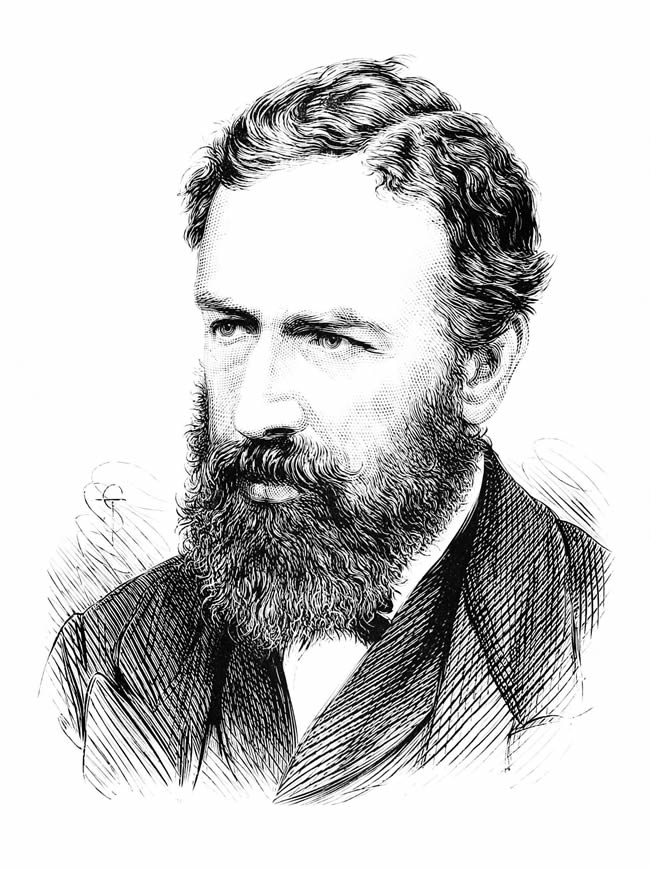

Energy efficiency sounds simple, but it’s rather difficult to measure. Sure when you purchase a shiny, new more energy efficient washing machine compared with your previous model you’re making a personal dent in energy consumption. But, what if in aggregate overall consumption increases because more people want that energy efficient model? In a nutshell, that’s Jevons Paradox, named after a 19th-century British economist, William Jevons. He observed that while the steam engine consumed energy more efficiently from coal, it also stimulated so much economic growth that coal consumption actually increased. Thus, Jevons argued that improvements in fuel efficiency tend to increase, rather than decrease, fuel use.

Energy efficiency sounds simple, but it’s rather difficult to measure. Sure when you purchase a shiny, new more energy efficient washing machine compared with your previous model you’re making a personal dent in energy consumption. But, what if in aggregate overall consumption increases because more people want that energy efficient model? In a nutshell, that’s Jevons Paradox, named after a 19th-century British economist, William Jevons. He observed that while the steam engine consumed energy more efficiently from coal, it also stimulated so much economic growth that coal consumption actually increased. Thus, Jevons argued that improvements in fuel efficiency tend to increase, rather than decrease, fuel use.

John Tierney over at the New York Times brings Jevons into the 21st century and discovers that the issues remain the same.

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

For the sake of a cleaner planet, should Americans wear dirtier clothes?

This is not a simple question, but then, nothing about dirty laundry is simple anymore. We’ve come far since the carefree days of 1996, when Consumer Reports tested some midpriced top-loaders and reported that “any washing machine will get clothes clean.”

In this year’s report, no top-loading machine got top marks for cleaning. The best performers were front-loaders costing on average more than $1,000. Even after adjusting for inflation, that’s still $350 more than the top-loaders of 1996.

What happened to yesterday’s top-loaders? To comply with federal energy-efficiency requirements, manufacturers made changes like reducing the quantity of hot water. The result was a bunch of what Consumer Reports called “washday wash-outs,” which left some clothes “nearly as stained after washing as they were when we put them in.”

Now, you might think that dirtier clothes are a small price to pay to save the planet. Energy-efficiency standards have been embraced by politicians of both parties as one of the easiest ways to combat global warming. Making appliances, cars, buildings and factories more efficient is called the “low-hanging fruit” of strategies to cut greenhouse emissions.

But a growing number of economists say that the environmental benefits of energy efficiency have been oversold. Paradoxically, there could even be more emissions as a result of some improvements in energy efficiency, these economists say.

The problem is known as the energy rebound effect. While there’s no doubt that fuel-efficient cars burn less gasoline per mile, the lower cost at the pump tends to encourage extra driving. There’s also an indirect rebound effect as drivers use the money they save on gasoline to buy other things that produce greenhouse emissions, like new electronic gadgets or vacation trips on fuel-burning planes.

[div class=attrib]Read more here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Wikipedia, Popular Science Monthly / Creative Commons.[end-div]