Time seems to unfold over different — lengthier — scales in the desert southwest of the United States. Perhaps it’s the vastness of the eerie landscape that puts fleeting human moments into the context of deep geologic time. Or, perhaps it’s our monumental human structures that aim to encode our present for the distant future. Structures like the Hoover Dam, which regulates the mighty Colorado River, and the ill-fated Yucca Mountain project, once designed to store the nation’s nuclear waste, were conceived to last many centuries.

Time seems to unfold over different — lengthier — scales in the desert southwest of the United States. Perhaps it’s the vastness of the eerie landscape that puts fleeting human moments into the context of deep geologic time. Or, perhaps it’s our monumental human structures that aim to encode our present for the distant future. Structures like the Hoover Dam, which regulates the mighty Colorado River, and the ill-fated Yucca Mountain project, once designed to store the nation’s nuclear waste, were conceived to last many centuries.

Yet these monuments to our impermanence raise a important issue beyond their construction — how are we to communicate their intent to humans living in a distant future, humans who will no longer be using any of our existing languages? Directions and warnings in English or contextual signs and images will not suffice. Consider Yucca Mountain. Now shuttered, Yucca Mountain was designed to be a repository for nuclear byproducts and waste from military and civilian programs. Keep in mind that some products of nuclear reactors, such as various isotopes of uranium, plutonium, technetium and neptunium, remain highly radioactive for tens of thousands to millions of years. So, how would we post warnings at Yucca Mountain about the entombed dangers to generations living 10,000 years and more from now? Those behind the Yucca Mountain project considered a number of fantastic (in its original sense) programs to carry dire warnings into the distant future including hostile architecture, radioactive cats and a pseudo-religious order. This was the work of the Human Interference Task Force.

From Motherboard:

Building the Hoover Dam rerouted the most powerful river in North America. It claimed the lives of 96 workers, and the beloved site dog, Little Niggy, who is entombed by the walkway in the shade of the canyon wall. Diverting the Colorado destroyed the ecology of the region, threatening fragile native plant life and driving several species of fish nearly to extinction. The dam brought water to 8 million people and created more than 5000 jobs. It required 6.6 million metric tons of concrete, all made from the desert; enough, famously, to pave a two lane road coast to coast across the US. Inside the dam’s walls that concrete is still curing, and will be for another 60 years.

Erik, photojournalist, and I have come here to try and get the measure of this place. Nevada is the uncanny locus of disparate monuments all concerned with charting deep time, leaving messages for future generations of human beings to puzzle over the meaning of: a star map, a nuclear waste repository and a clock able to keep time for 10,000 years—all of them within a few hours drive of Las Vegas through the harsh desert.

Hoover Dam is theorized in some structural stress projections to stand for tens of thousands of years from now, and what could be its eventual undoing is mussels. The mollusks which grow in the dam’s grates will no longer be scraped away, and will multiply eventually to such density that the built up stress of the river will burst the dam’s wall. That is if the Colorado continues to flow. Otherwise erosion will take much longer to claim the structure, and possibly Oskar J.W. Hansen’s vision will be realized: future humans will find the dam 14,000 years from now, at the end of the current Platonic Year.

A Platonic Year lasts for roughly 26,000 years. It’s also known as the precession of the equinoxes, first written into the historical record in the second century BC by the Greek mathematician, Hipparchus, though there is evidence that earlier people also solved this complex equation. Earth rotates in three ways: 365 days around the sun, on its 24 hours axis and on its precessional axis. The duration of the last is the Platonic Year, where Earth is incrementally turning on a tilt pointing to its true north as the Sun’s gravity pulls on us, leaving our planet spinning like a very slow top along its orbit around the sun.

Now Earth’s true-north pole star is Polaris, in Ursa Minor, as it was at the completion of Hoover Dam. At the end of the current Platonic Year it will be Vega, in the constellation Lyra. Hansen included this information in an amazingly accurate astronomical clock, or celestial map, embedded in the terrazzo floor of the dam’s dedication monument. Hansen wanted any future humans who came across the dam to be able to know exactly when it was built.

He used the clock to mark major historical events of the last several thousand years including the birth of Christ and the building of the pyramids, events which he thought were equal to the engineering feat of men bringing water to a desert in the 1930s. He reasoned that though current languages could be dead in this future, any people who had survived that long would have advanced astronomy, math and physics in their arsenal of survival tactics. Despite this, the monument is written entirely in English, which is for the benefit of current visitors, not our descendents of millennia from now.

The Hoover Dam is staggering. It is frankly impossible, even standing right on top of it, squinting in the blinding sunlight down its vertiginous drop, to imagine how it was ever built by human beings; even as I watch old documentary footage on my laptop back in the hotel at night on Fremont Street, showing me that exact thing, I don’t believe it. I cannot square it in my mind. I cannot conceive of nearly dying every day laboring in the brutally dry 100 degree heat, in a time before air-conditioning, in a time before being able to ever get even the slightest relief from the elements.

Hansen was more than aware of our propensity to build great monuments to ourselves and felt the weight of history as he submitted his bid for the job to design the dedication monument, writing, “Mankind itself is the subject of the sculptures at Hoover Dam.” Joan Didion described it as the most existentially terrifying place in America: “Since the afternoon in 1967 when I first saw Hoover Dam, its image has never been entirely absent from my inner eye.” Thirty-two people have chosen the dam as their place of suicide. It has no fences.

The reservoir is now the lowest it has ever been and California is living through the worst drought in 1200 years. You can swim in Lake Mead, so we did, sort of. It did provide some cool respite for a moment from the unrelenting heat of the desert. We waded around only up to our ankles because it smelled pretty terrible, the shoreline dirty with garbage.

…

Radioactive waste from spent nuclear fuel has a shelf life of hundreds of thousands of years. Maybe even more than a million, it’s not possible to precisely predict. Nuclear power plants around the US have produced 150 million metric tons of highly active nuclear waste that sits at dozens of sites around the country, awaiting a place to where it can all be carted and buried thousands of feet underground to be quarantined for the rest of time. For now a lot of it sits not far from major cities.

Yucca Mountain, 120 miles from Hoover Dam, is not that place. The site is one of the most intensely geologically surveyed and politically controversial pieces of land on Earth. Since 1987 it has been, at the cost of billions of dollars, the highly contested resting place for the majority of America’s high-risk nuclear waste. Those plans were officially shuttered in 2012, after states sued each other, states sued the federal Government, the Government sued contractors, and the people living near Yucca Mountain didn’t want, it turned out, for thousands of tons of nuclear waste to be carted through their counties and sacred lands via rail. President Obama cancelled its funding and officially ended the project.

It was said that there was a fault line running directly under the mountain; that the salt rock was not as absorbent as it was initially thought to be and that it posed the threat of leaking radiation into the water table; that more recently the possibility of fracking in the area would beget an ecological disaster. That a 10,000 year storage solution was nowhere near long enough to inculcate the Earth from the true shelf-life of the waste, which is realistically thought to be dangerous for many times that length of time. The site is now permanently closed, visible only from a distance through a cacophony of government warning signs blockading a security checkpoint.

We ask around the community of Amargosa Valley about the mountain. Sitting on 95 it’s the closest place to the site and consists only of a gas station, which trades in a huge amount of Area 51 themed merchandise, a boldly advertised sex shop, an alien motel and a firework store where you can let off rockets in the car park. Across the road is the vacant lot of what was once an RV park, with a couple of badly busted up vehicles looted beyond recognition and a small aquamarine boat lying on its side in the dirt.

At the gas station register a woman explains that no one really liked the idea of having waste so close to their homes (she repeats the story of the fault line), but they did like the idea of jobs, hundreds of which disappeared along with the project, leaving the surrounding areas, mainly long-tapped out mining communities, even more severely depressed.

We ask what would happen if we tried to actually get to the mountain itself, on government land.

“Plenty of people do try,” she says. “They’re trying to get to Area 51. They have sensors though, they’ll come get you real quick in their truck.”

Would we get shot?

“Shot? No. But they would throw you on the ground, break all your cameras and interrogate you for a long time.”

We decide just to take the road that used to go to the mountain as far as we can to the checkpoint, where in the distance beyond the electric fences at the other end of a stretch of desert land we see buildings and cars parked and most definitely some G-men who would see us before we even had the chance to try and sneak anywhere.

Before it was shut for good, Yucca Mountain had kilometers of tunnels bored into it and dozens of experiments undertaken within it, all of it now sealed behind an enormous vault door. It was also the focus of a branch of linguistics established specifically to warn future humans of the dangers of radioactive waste: nuclear semiotics. The Human Interference Task Force—a consortium of archeologists, architects, linguists, philosophers, engineers, designers—faced the opposite problem to Oskar Hansen at Hoover Dam; the Yucca Mountain repository was not hoping to attract the attentions of future humans to tell them of the glory of their forebears; it was to tell them that this place would kill them if they trod too near.

To create a universally readable warning system for humans living thirty generations from now, the signs will have to be instantly recognizable as expressing an immediate and lethal danger, as well as a deep sense of shunning: these were impulses that came up against each other; how to adequately express that the place was deadly while not at the same time enticing people to explore it, thinking it must contain something of great value if so much trouble had been gone to in order to keep people away? How to express this when all known written languages could very easily be dead? Signs as we know them now would almost certainly be completely unintelligible free of their social contexts which give them current meaning; a nuclear waste sign is just a dot with three rounded triangles sticking out of it to anyone not taught over a lifetime to know its warning.

Read the entire story here.

Image: United Nations radioactive symbol, 2007.

What do you get when you set AI (artificial intelligence) the task of reading through 30,000 Danish folk and fairy tales? Well, you get a host of fascinating, newly discovered insights into Scandinavian witches and trolls.

What do you get when you set AI (artificial intelligence) the task of reading through 30,000 Danish folk and fairy tales? Well, you get a host of fascinating, newly discovered insights into Scandinavian witches and trolls.

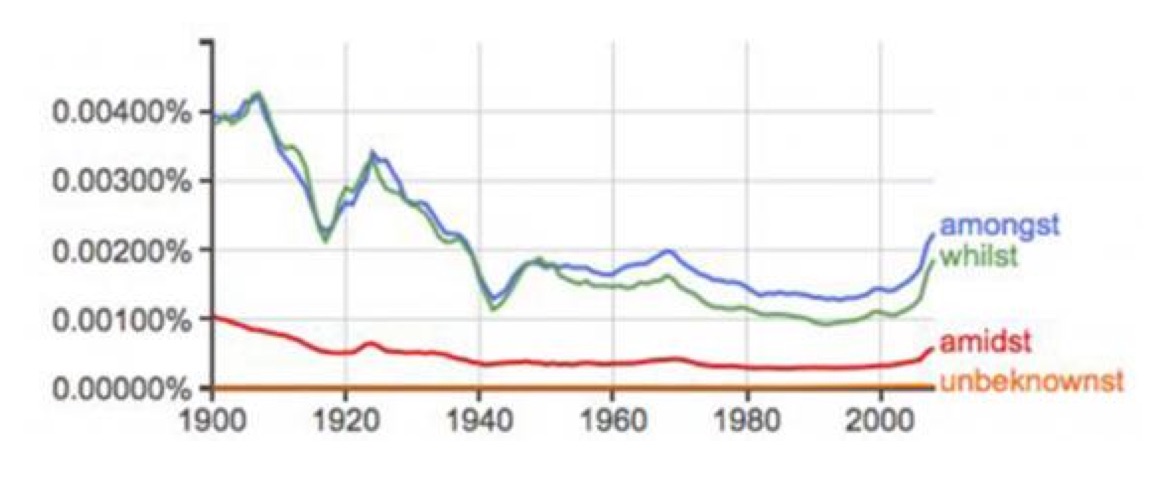

Some words give us the creeps, they raise the hair on back of our heads, they make us squirm and give us an internal shudder. “Moist” is such as word.

Some words give us the creeps, they raise the hair on back of our heads, they make us squirm and give us an internal shudder. “Moist” is such as word. Peter Ludlow, professor of philosophy at Northwestern University, has authored a number of fascinating articles on the philosophy of language and linguistics. Here he discusses his view of language as a dynamic, living organism. Literalists take note.

Peter Ludlow, professor of philosophy at Northwestern University, has authored a number of fascinating articles on the philosophy of language and linguistics. Here he discusses his view of language as a dynamic, living organism. Literalists take note.

[div class=attrib]From Eurozine:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Eurozine:[end-div]