I thought it rather appropriate to revisit Burning Man one day after Guy Fawkes Day in the UK. I must say that Burning Man has grown into more of a corporate event compared with the cheesy pyrotechnic festivities in Britain on the 5th of November. So, even though Burners have a bigger, bolder, brasher event please remember-remember, we Brits had the original burning man — by 380 years.

The once-counter-cultural phenomenon known as Burning Man seems to be maturing into an executive-level tech-fest. Let’s face it, if I can read about the festival in the mainstream media it can’t be as revolutionary as it once set out to be. Though, the founders‘ desire to keep the festival radically inclusive means that organizers can’t turn away those who may end up razing Burning Man to the ground due to corporate excess. VCs and the tech elite from Silicon Valley now descend in their hoards, having firmly placed Burning Man on their app-party circuit. Until recently, Burners mingled relatively freely throughout the week-long temporary metropolis in the Nevada desert; now, the nouveau riche arrive on private jets and “camp” in exclusive wagon-circles of luxury RVs catered to by corporate chefs and personal costume designers. It certainly seems like some of Larry Harvey’s 10 Principles delineating Burning Man’s cultural ethos are on shaky ground. Oh well, capitalism ruins another great idea! But, go once before you die.

From NYT:

There are two disciplines in which Silicon Valley entrepreneurs excel above almost everyone else. The first is making exorbitant amounts of money. The second is pretending they don’t care about that money.

To understand this, let’s enter into evidence Exhibit A: the annual Burning Man festival in Black Rock City, Nev.

If you have never been to Burning Man, your perception is likely this: a white-hot desert filled with 50,000 stoned, half-naked hippies doing sun salutations while techno music thumps through the air.

A few years ago, this assumption would have been mostly correct. But now things are a little different. Over the last two years, Burning Man, which this year runs from Aug. 25 to Sept. 1, has been the annual getaway for a new crop of millionaire and billionaire technology moguls, many of whom are one-upping one another in a secret game of I-can-spend-more-money-than-you-can and, some say, ruining it for everyone else.

Some of the biggest names in technology have been making the pilgrimage to the desert for years, happily blending in unnoticed. These include Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the Google founders, and Jeff Bezos, chief executive of Amazon. But now a new set of younger rich techies are heading east, including Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, employees from Twitter, Zynga and Uber, and a slew of khaki-wearing venture capitalists.

Before I explain just how ridiculous the spending habits of these baby billionaires have become, let’s go over the rules of Burning Man: You bring your own place to sleep (often a tent), food to eat (often ramen noodles) and the strangest clothing possible for the week (often not much). There is no Internet or cell reception. While drugs are technically illegal, they are easier to find than candy on Halloween. And as for money, with the exception of coffee and ice, you cannot buy anything at the festival. Selling things to people is also a strict no-no. Instead, Burners (as they are called) simply give things away. What’s yours is mine. And that often means everything from a meal to saliva.

In recent years, the competition for who in the tech world could outdo who evolved from a need for more luxurious sleeping quarters. People went from spending the night in tents, to renting R.V.s, to building actual structures.

“We used to have R.V.s and precooked meals,” said a man who attends Burning Man with a group of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. (He asked not to be named so as not to jeopardize those relationships.) “Now, we have the craziest chefs in the world and people who build yurts for us that have beds and air-conditioning.” He added with a sense of amazement, “Yes, air-conditioning in the middle of the desert!”

His camp includes about 100 people from the Valley and Hollywood start-ups, as well as several venture capital firms. And while dues for most non-tech camps run about $300 a person, he said his camp’s fees this year were $25,000 a person. A few people, mostly female models flown in from New York, get to go free, but when all is told, the weekend accommodations will collectively cost the partygoers over $2 million.

This is drastically different from the way most people experience the event. When I attended Burning Man a few years ago, we slept in tents and a U-Haul moving van. We lived on cereal and beef jerky for a week. And while Burning Man was one of the best experiences of my life, using the public Porta-Potty toilets was certainly one of the most revolting experiences thus far. But that’s what makes Burning Man so great: at least you’re all experiencing those gross toilets together.

That is, until recently. Now the rich are spending thousands of dollars to get their own luxury restroom trailers, just like those used on movie sets.

“Anyone who has been going to Burning Man for the last five years is now seeing things on a level of expense or flash that didn’t exist before,” said Brian Doherty, author of the book “This Is Burning Man.” “It does have this feeling that, ‘Oh, look, the rich people have moved into my neighborhood.’ It’s gentrifying.”

For those with even more money to squander, there are camps that come with “Sherpas,” who are essentially paid help.

Tyler Hanson, who started going to Burning Man in 1995, decided a couple of years ago to try working as a paid Sherpa at one of these luxury camps. He described the experience this way: Lavish R.V.s are driven in and connected together to create a private forted area, ensuring that no outsiders can get in. The rich are flown in on private planes, then picked up at the Burning Man airport, driven to their camp and served like kings and queens for a week. (Their meals are prepared by teams of chefs, which can include sushi, lobster boils and steak tartare — yes, in the middle of 110-degree heat.)

“Your food, your drugs, your costumes are all handled for you, so all you have to do is show up,” Mr. Hanson said. “In the camp where I was working, there were about 30 Sherpas for 12 attendees.”

Mr. Hanson said he won’t be going back to Burning Man anytime soon. The Sherpas, the money, the blockaded camps and the tech elite were too much for him. “The tech start-ups now go to Burning Man and eat drugs in search of the next greatest app,” he said. “Burning Man is no longer a counterculture revolution. It’s now become a mirror of society.”

Strangely, the tech elite won’t disagree with Mr. Hanson about it being a reflection of society. This year at the premiere of the HBO show “Silicon Valley,” Elon Musk, an entrepreneur who was a founder of PayPal, complained that Mike Judge, the show’s creator, didn’t get the tech world because — wait for it — he had not attended the annual party in the desert.

“I really feel like Mike Judge has never been to Burning Man, which is Silicon Valley,” Mr. Musk said to a Re/Code reporter, while using a number of expletives to describe the festival. “If you haven’t been, you just don’t get it.”

Read the entire story here.

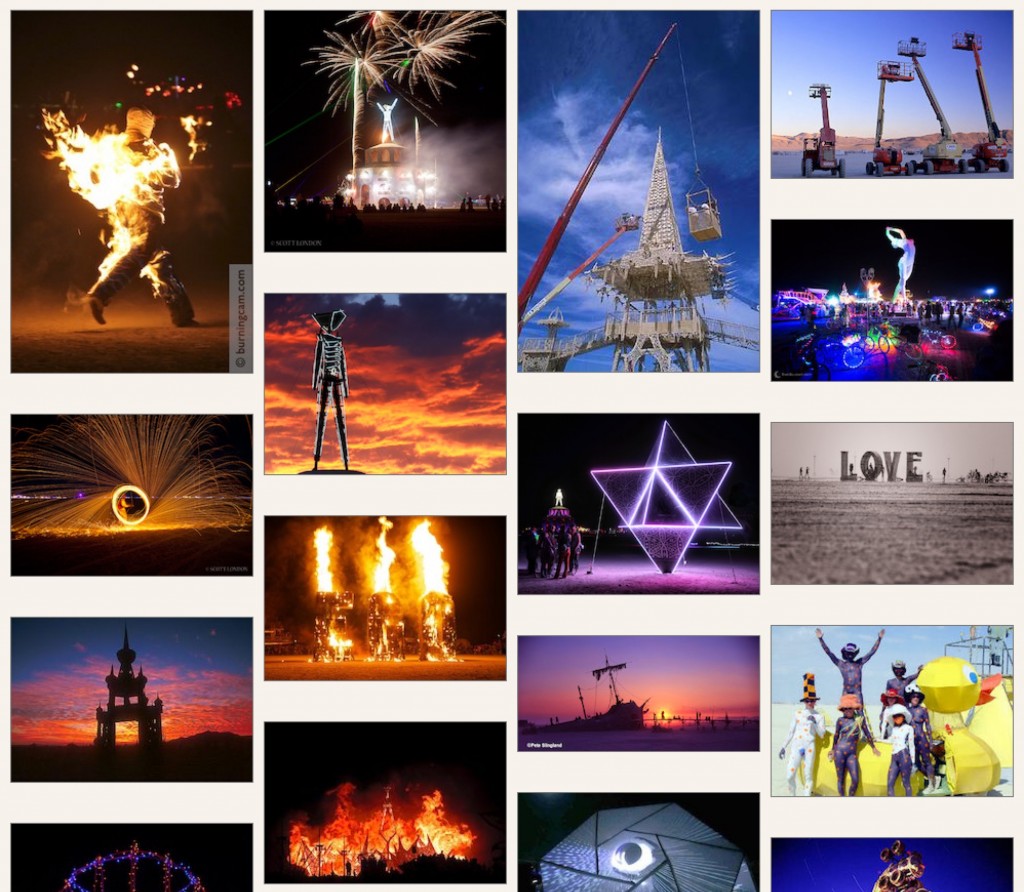

Image: Burning Man gallery. Courtesy of Burners.

Artist Ai Weiwei has suffered at the hands of the Chinese authorities much more so than Andy Warhol’s brushes with surveillance from the FBI. Yet the two are remarkably similar: brash and polarizing views, distinctive art and creative processes, masterful self-promotion, savvy media manipulation and global ubiquity. This is all the more astounding given Ai Weiwei’s arrest, detentions and prohibition on travel outside of Beijing. He’s even made it to the Venice Biennale this year — only his art of course.

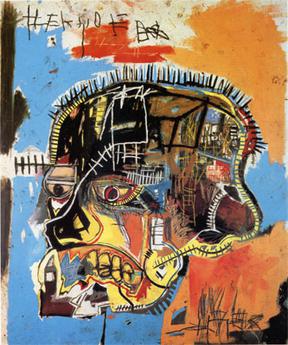

Artist Ai Weiwei has suffered at the hands of the Chinese authorities much more so than Andy Warhol’s brushes with surveillance from the FBI. Yet the two are remarkably similar: brash and polarizing views, distinctive art and creative processes, masterful self-promotion, savvy media manipulation and global ubiquity. This is all the more astounding given Ai Weiwei’s arrest, detentions and prohibition on travel outside of Beijing. He’s even made it to the Venice Biennale this year — only his art of course. That a small group of Young British Artists (YBA) made an impact on the art scene in the UK and across the globe over the last 25 years is without question. Though, whether the public at large will, 10, 25 or 50 years from now (and beyond), recognize a Damien Hirst spin painting or Tracy Emin’s “My Bed” or a Sarah Lucas self-portrait — “The Artist Eating a Banana” springs to mind — remains an open question.

That a small group of Young British Artists (YBA) made an impact on the art scene in the UK and across the globe over the last 25 years is without question. Though, whether the public at large will, 10, 25 or 50 years from now (and beyond), recognize a Damien Hirst spin painting or Tracy Emin’s “My Bed” or a Sarah Lucas self-portrait — “The Artist Eating a Banana” springs to mind — remains an open question.

Only yesterday we

Only yesterday we

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question:

Simon Coonan over a Slate posits a simple question: Accessorize

Accessorize

Slip

Slip

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

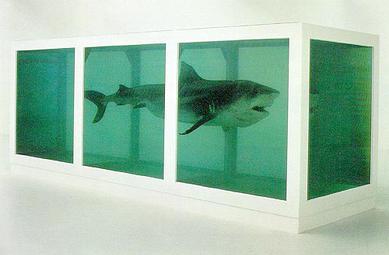

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div] Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years.

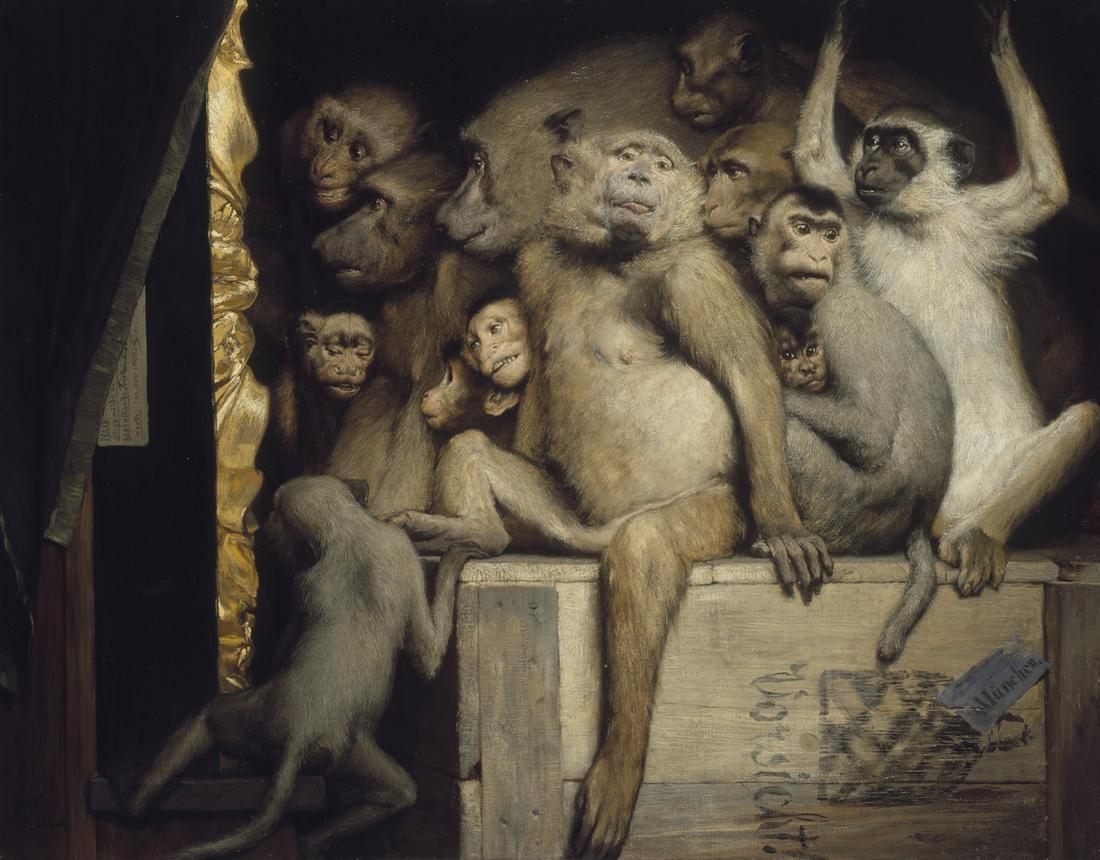

Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years. Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox.

Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox. [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

Artist

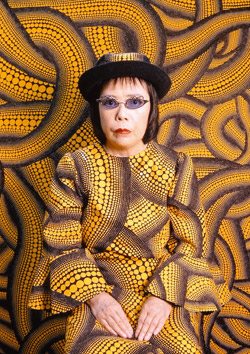

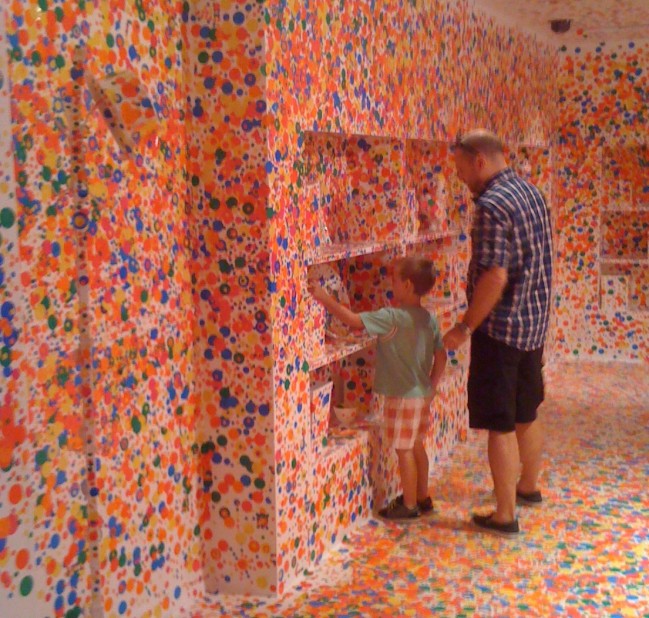

Artist  The guests were chic, the bordeaux was sipped with elegant restraint and the hostess was suitably glamorous in a canary yellow cocktail dress. To an outside observer who made it past the soirée privée sign on the door of the Anne de Villepoix gallery on Thursday night, it would have seemed the quintessential Parisian art viewing.

The guests were chic, the bordeaux was sipped with elegant restraint and the hostess was suitably glamorous in a canary yellow cocktail dress. To an outside observer who made it past the soirée privée sign on the door of the Anne de Villepoix gallery on Thursday night, it would have seemed the quintessential Parisian art viewing. [div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div]