From the Public Domain Review comes a fascinating tale of hydraulic automata, mechanical monkeys, automatic organs and a host of other beautiful robotic inventions predating our current technological revolution by hundreds of years. These wonderful contraptions span the siphonic inventions of 1st-century-AD engineer Hero of Alexandria to the speaking machines and the chess playing mechanical Turk of Hungarian engineer Wolfgang von Kempelen from the late-1700s.

My favorite is the infamous “Defecating Duck”. Designed in the mid-18th century by Frenchman Jacques Vaucanson, the duck was one of the first simulative automata. The mechanical duck flapped its wings and moved much like its real world cousin, but its claim to fame was its ability to peck and swallow bits of food and excrete “droppings”.

More from Public Domain Review:

How old are the fields of robotics and artificial intelligence? Many might trace their origins to the mid-twentieth century, and the work of people such as Alan Turing, who wrote about the possibility of machine intelligence in the ‘40s and ‘50s, or the MIT engineer Norbert Wiener, a founder of cybernetics. But these fields have prehistories — traditions of machines that imitate living and intelligent processes — stretching back centuries and, depending how you count, even millennia.

The word “robot” made its first appearance in a 1920 play by the Czech writer Karel ?apek entitled R.U.R., for Rossum’s Universal Robots. Deriving his neologism from the Czech word “robota,” meaning “drudgery” or “servitude,” ?apek used “robot” to refer to a race of artificial humans who replace human workers in a futurist dystopia. (In fact, the artificial humans in the play are more like clones than what we would consider robots, grown in vats rather than built from parts.)

There was, however, an earlier word for artificial humans and animals, “automaton”, stemming from Greek roots meaning “self-moving”. This etymology was in keeping with Aristotle’s definition of living beings as those things that could move themselves at will. Self-moving machines were inanimate objects that seemed to borrow the defining feature of living creatures: self-motion. The first-century-AD engineer Hero of Alexandria described lots of automata. Many involved elaborate networks of siphons that activated various actions as the water passed through them, especially figures of birds drinking, fluttering, and chirping.

Read the entire article here.

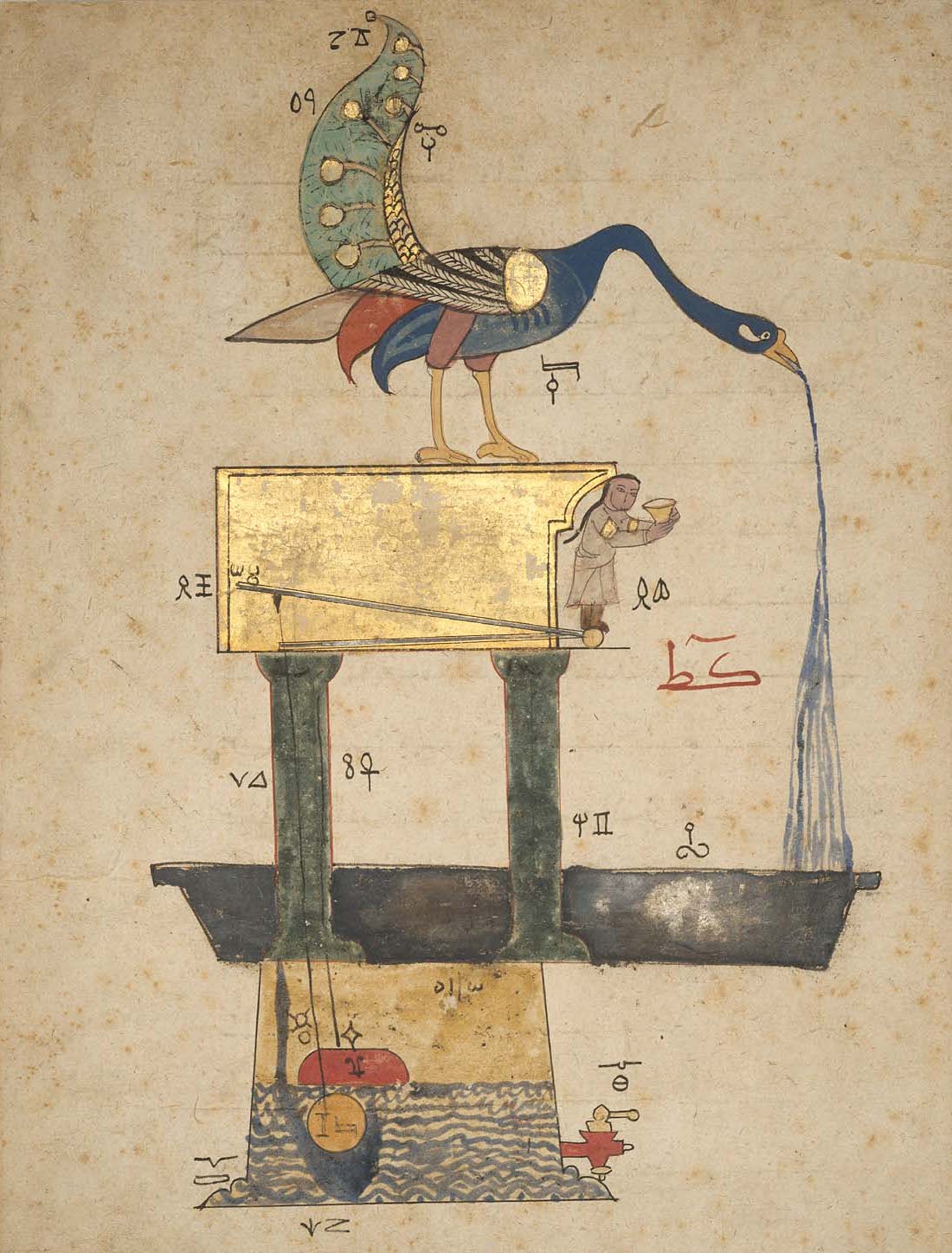

Image: Illustration of the peacock fountain, from a 14th-century edition of Al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Courtesy: Public Domain Review.