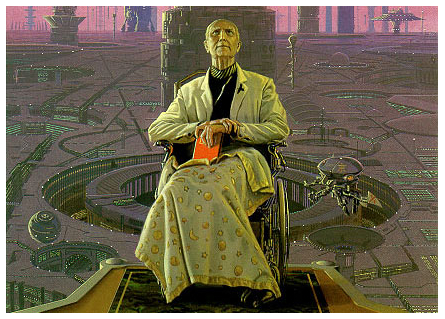

Fans of Isaac Asimov’s groundbreaking Foundation novels will know Hari Seldon as the founder of “psychohistory”. Entirely fictional, psychohistory is a statistical science that makes possible predictions of future behavior of large groups of people, and is based on a mathematical analysis of history and sociology.

Fans of Isaac Asimov’s groundbreaking Foundation novels will know Hari Seldon as the founder of “psychohistory”. Entirely fictional, psychohistory is a statistical science that makes possible predictions of future behavior of large groups of people, and is based on a mathematical analysis of history and sociology.

Now, 11,000 years or so back into our present reality comes the burgeoning field of “neuroeconomics”. As Slate reports, Seldon’s “psychohistory” may not be as far-fetched or as far away as we think.

[div class=attrib]From Slate:[end-div]

Neuroscience—the science of how the brain, that physical organ inside one’s head, really works—is beginning to change the way we think about how people make decisions. These findings will inevitably change the way we think about how economies function. In short, we are at the dawn of “neuroeconomics.”

Efforts to link neuroscience and economics have occurred mostly in just the last few years, and the growth of neuroeconomics is still in its early stages. But its nascence follows a pattern: Revolutions in science tend to come from completely unexpected places. A field of science can turn barren if no fundamentally new approaches to research are on the horizon. Scholars can become so trapped in their methods—in the language and assumptions of the accepted approach to their discipline—that their research becomes repetitive or trivial.

Then something exciting comes along from someone who was never involved with these methods—some new idea that attracts young scholars and a few iconoclastic old scholars, who are willing to learn a different science and its research methods. At some moment in this process, a scientific revolution is born.

The neuroeconomic revolution has passed some key milestones quite recently, notably the publication last year of neuroscientist Paul Glimcher’s book Foundations of Neuroeconomic Analysis—a pointed variation on the title of Paul Samuelson’s 1947 classic work, Foundations of Economic Analysis, which helped to launch an earlier revolution in economic theory.

…

Much of modern economic and financial theory is based on the assumption that people are rational, and thus that they systematically maximize their own happiness, or as economists call it, their “utility.” When Samuelson took on the subject in his 1947 book, he did not look into the brain, but relied instead on “revealed preference.” People’s objectives are revealed only by observing their economic activities. Under Samuelson’s guidance, generations of economists have based their research not on any physical structure underlying thought and behavior, but on the assumption of rationality.

…

While Glimcher and his colleagues have uncovered tantalizing evidence, they have yet to find most of the fundamental brain structures. Maybe that is because such structures simply do not exist, and the whole utility-maximization theory is wrong, or at least in need of fundamental revision. If so, that finding alone would shake economics to its foundations.

Another direction that excites neuroscientists is how the brain deals with ambiguous situations, when probabilities are not known or other highly relevant information is not available. It has already been discovered that the brain regions used to deal with problems when probabilities are clear are different from those used when probabilities are unknown. This research might help us to understand how people handle uncertainty and risk in, say, financial markets at a time of crisis.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Hari Seldon, Foundation by Isaac Asimov.[end-div]