“Death Cafe” sounds like the name of a group of alternative musicians from Denmark. But it’s not. Its rather more literal definition is a coffee shop where customers go to talk about death over a cup of earl grey tea or double shot espresso. And, while it’s not displacing Starbucks (yet), death cafes are a growing trend in Europe, first inspired by the pop-up Cafe Mortels of Switzerland.

“Death Cafe” sounds like the name of a group of alternative musicians from Denmark. But it’s not. Its rather more literal definition is a coffee shop where customers go to talk about death over a cup of earl grey tea or double shot espresso. And, while it’s not displacing Starbucks (yet), death cafes are a growing trend in Europe, first inspired by the pop-up Cafe Mortels of Switzerland.

[div class=attrib]From the Independent:[end-div]

Do you have a death wish?” is not a question normally bandied about in seriousness. But have you ever actually asked whether a parent, partner or friend has a wish, or wishes, concerning their death? Burial or cremation? Where would they like to die? It’s not easy to do.

Stiff-upper-lipped Brits have a particular problem talking about death. Anyone who tries invariably gets shouted down with “Don’t talk like that!” or “If you say it, you’ll make it happen.” A survey by the charity Dying Matters reveals that more than 70 per cent of us are uncomfortable talking about death and that less than a third of us have spoken to family members about end-of-life wishes.

But despite this ingrained reluctance there are signs of burgeoning interest in exploring death. I attended my first death cafe recently and was surprised to discover that the gathering of goths, emos and the terminally ill that I’d imagined, turned out to be a collection of fascinating, normal individuals united by a wish to discuss mortality.

At a trendy coffee shop called Cakey Muto in Hackney, east London, taking tea (and scones!) with death turned out to be rather a lot of fun. What is believed to be the first official British death cafe took place in September last year, organised by former council worker Jon Underwood. Since then, around 150 people have attended death cafes in London and the one I visited was the 17th such happening.

“We don’t want to shove death down people’s throats,” Underwood says. “We just want to create an environment where talking about death is natural and comfortable.” He got the idea from the Swiss model (cafe mortel) invented by sociologist Bernard Crettaz, the popularity of which gained momentum in the Noughties and has since spread to France.

Underwood is keen to start a death cafe movement in English-speaking countries and his website (deathcafe.com) includes instructions for setting up your own. He has already inspired the first death cafe in America and groups have sprung up in Northern England too. Last month, he arranged the first death cafe targeting issues around dying for a specific group, the LGBT community, which he says was extremely positive and had 22 attendees.

Back in Cakey Muto, 10 fellow attendees and I eye each other nervously as the cafe door is locked and we seat ourselves in a makeshift circle. Conversation is kicked off by our facilitator, grief specialist Kristie West, who sets some ground rules. “This is a place for people to talk about death,” she says. “I want to make it clear that it is not about grief, even though I’m a grief specialist. It’s also not a debate platform. We don’t want you to air all your views and pick each other apart.”

A number of our party are directly involved in the “death industry”: a humanist-funeral celebrant, an undertaker and a lady who works in a funeral home. Going around the circle explaining our decision to come to a death cafe, what came across from this trio, none of whom knew each other, was their satisfaction in their work.

“I feel more alive than ever since working in a funeral home,” one of the women remarked. “It has helped me recognise that it isn’t a circle between life and death, it is more like a cosmic soup. The dead and the living are sort of floating about together.”

Others in the group include a documentary maker, a young woman whose mother died 18 months ago, a lady who doesn’t say much but was persuaded by her neighbour to come, and a woman who has attended three previous death cafes but still hasn’t managed to admit this new interest to her family or get them to talk about death.

The funeral celebrant tells the circle she’s been thinking a lot about what makes a good or bad death. She describes “the roaring corrosiveness of stepping into a household” where a “bad death” has taken place and the group meditates on what a bad death entails: suddenness, suffering and a difficult relationship between the deceased and bereaved?

“I have seen people have funerals which I don’t think they would have wanted,” says the undertaker, who has 17 years of experience. “It is possible to provide funerals more cheaply, more sensitively and with greater respect for the dead.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

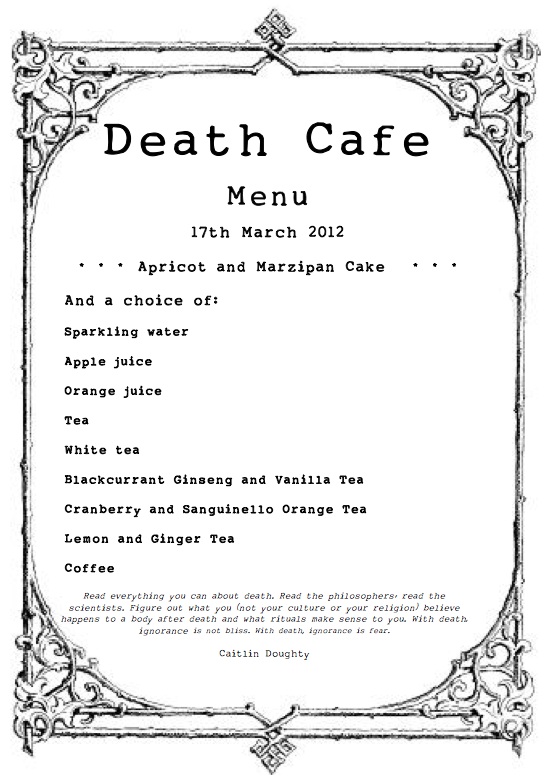

[div class=attrib]Death cafe menu courtesy of Death Cafe.[end-div]