The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN made headlines in 2012 with the announcement of a probable discovery of the Higgs Boson. Scientists are collecting and analyzing more data before they declare an outright discovery in 2013. In the meantime, they plan to use the giant machine to examine even more interesting science — at very small and very large scales — in the new year.

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

When it comes to shutting down the most powerful atom smasher ever built, it’s not simply a question of pressing the off switch.

In the French-Swiss countryside on the far side of Geneva, staff at the Cern particle physics laboratory are taking steps to wind down the Large Hadron Collider. After the latest run of experiments ends next month, the huge superconducting magnets that line the LHC’s 27km-long tunnel must be warmed up, slowly and gently, from -271 Celsius to room temperature. Only then can engineers descend into the tunnel to begin their work.

The machine that last year helped scientists snare the elusive Higgs boson – or a convincing subatomic impostor – faces a two-year shutdown while engineers perform repairs that are needed for the collider to ramp up to its maximum energy in 2015 and beyond. The work will beef up electrical connections in the machine that were identified as weak spots after an incident four years ago that knocked the collider out for more than a year.

The accident happened days after the LHC was first switched on in September 2008, when a short circuit blew a hole in the machine and sprayed six tonnes of helium into the tunnel that houses the collider. Soot was scattered over 700 metres. Since then, the machine has been forced to run at near half its design energy to avoid another disaster.

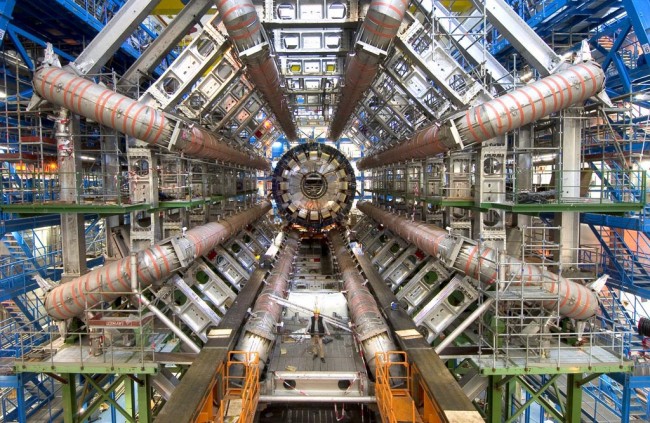

The particle accelerator, which reveals new physics at work by crashing together the innards of atoms at close to the speed of light, fills a circular, subterranean tunnel a staggering eight kilometres in diameter. Physicists will not sit around idle while the collider is down. There is far more to know about the new Higgs-like particle, and clues to its identity are probably hidden in the piles of raw data the scientists have already gathered, but have had too little time to analyse.

But the LHC was always more than a Higgs hunting machine. There are other mysteries of the universe that it may shed light on. What is the dark matter that clumps invisibly around galaxies? Why are we made of matter, and not antimatter? And why is gravity such a weak force in nature? “We’re only a tiny way into the LHC programme,” says Pippa Wells, a physicist who works on the LHC’s 7,000-tonne Atlas detector. “There’s a long way to go yet.”

The hunt for the Higgs boson, which helps explain the masses of other particles, dominated the publicity around the LHC for the simple reason that it was almost certainly there to be found. The lab fast-tracked the search for the particle, but cannot say for sure whether it has found it, or some more exotic entity.

“The headline discovery was just the start,” says Wells. “We need to make more precise measurements, to refine the particle’s mass and understand better how it is produced, and the ways it decays into other particles.” Scientists at Cern expect to have a more complete identikit of the new particle by March, when repair work on the LHC begins in earnest.

By its very nature, dark matter will be tough to find, even when the LHC switches back on at higher energy. The label “dark” refers to the fact that the substance neither emits nor reflects light. The only way dark matter has revealed itself so far is through the pull it exerts on galaxies.

Studies of spinning galaxies show they rotate with such speed that they would tear themselves apart were there not some invisible form of matter holding them together through gravity. There is so much dark matter, it outweighs by five times the normal matter in the observable universe.

The search for dark matter on Earth has failed to reveal what it is made of, but the LHC may be able to make the substance. If the particles that constitute it are light enough, they could be thrown out from the collisions inside the LHC. While they would zip through the collider’s detectors unseen, they would carry energy and momentum with them. Scientists could then infer their creation by totting up the energy and momentum of all the particles produced in a collision, and looking for signs of the missing energy and momentum.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article following the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: The eight torodial magnets can be seen on the huge ATLAS detector with the calorimeter before it is moved into the middle of the detector. This calorimeter will measure the energies of particles produced when protons collide in the centre of the detector. ATLAS will work along side the CMS experiment to search for new physics at the 14 TeV level. Courtesy of CERN.[end-div]