[div class=attrib]By Robert Pinsky for Slate:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]By Robert Pinsky for Slate:[end-div]

Poetry can resemble incantation, but sometimes it also resembles conversation. Certain poems combine the two—the cadences of speech intertwined with the forms of song in a varying way that heightens the feeling. As in a screenplay or in fiction, the things that people in a poem say can seem natural, even spontaneous, yet also work to propel the emotional action along its arc.

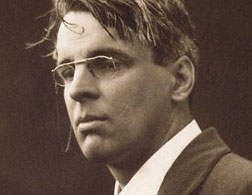

The casual surface of speech and the inward energy of art have a clear relation in “Adam’s Curse” by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939). A couple and their friend are together at the end of a summer day. In the poem, two of them speak, first about poetry and then about love. All of the poem’s distinct narrative parts—the setting, the dialogue, the stunning and unspoken conclusion—are conveyed in the strict form of rhymed couplets throughout. I have read the poem many times, for many years, and every time, something in me is hypnotized by the dance of sentence and rhyme. Always, in a certain way, the conclusion startles me. How can the familiar be somehow surprising? It seems to be a principle of art; and in this case, the masterful, unshowy rhyming seems to be a part of it. The couplet rhyme profoundly drives and tempers the gradually gathering emotional force of the poem in ways beyond analysis.

Yeats’ dialogue creates many nuances of tone. It is even a little funny at times: The poet’s self-conscious self-pity about how hard he works (he does most of the talking) is exaggerated with a smile, and his categories for the nonpoet or nonmartyr “world” have a similar, mildly absurd sweeping quality: bankers, schoolmasters, clergymen … This is not wit, exactly, but the slightly comical tone friends might use sitting together on a summer evening. I hear the same lightness of touch when the woman says, “Although they do not talk of it at school.” The smile comes closest to laughter when the poet in effect mocks himself gently, speaking of those lovers who “sigh and quote with learned looks/ Precedents out of beautiful old books.” The plain monosyllables of “old books” are droll in the context of these lovers. (Yeats may feel that he has been such a lover in his day.)

The plainest, most straightforward language in the poem, in some ways, comes at the very end—final words, not uttered in the conversation, are more private and more urgent than what has come before. After the almost florid, almost conventionally poetic description of the sunset, the courtly hint of a love triangle falls away. The descriptive language of the summer twilight falls away. The dialogue itself falls away—all yielding to the idea that this concluding thought is “only for your ears.” That closing passage of interior thoughts, what in fiction might be called “omniscient narration,” makes the poem feel, to me, as though not simply heard but overheard.

“Adam’s Curse”

We sat together at one summer’s end,

That beautiful mild woman, your close friend,

And you and I, and talked of poetry.

I said, “A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

Better go down upon your marrow-bones

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones

Like an old pauper, in all kinds of weather;

For to articulate sweet sounds together

Is to work harder than all these, and yet

Be thought an idler by the noisy set

Of bankers, schoolmasters, and clergymen

The martyrs call the world.”And thereupon

That beautiful mild woman for whose sake

There’s many a one shall find out all heartache

On finding that her voice is sweet and low

Replied, “To be born woman is to know—

Although they do not talk of it at school—

That we must labour to be beautiful.”

I said, “It’s certain there is no fine thing

Since Adam’s fall but needs much labouring.

There have been lovers who thought love should be

So much compounded of high courtesy

That they would sigh and quote with learned looks

Precedents out of beautiful old books;

Yet now it seems an idle trade enough.”We sat grown quiet at the name of love;

We saw the last embers of daylight die,

And in the trembling blue-green of the sky

A moon, worn as if it had been a shell

Washed by time’s waters as they rose and fell

About the stars and broke in days and years.I had a thought for no one’s but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove

To love you in the old high way of love;

That it had all seemed happy, and yet we’d grown

As weary-hearted as that hollow moon.

[div class=atrrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]