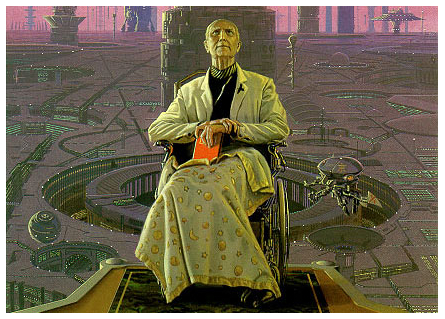

A previously unpublished essay by Isaac Asimov on the creative process shows us his well reasoned thinking on the subject. While he believed that deriving new ideas could be done productively in a group, he seemed to gravitate more towards the notion of the lone creative genius. Both, however, require the innovator(s) to cross-connect thoughts, often from disparate sources.

From Technology Review:

How do people get new ideas?

Presumably, the process of creativity, whatever it is, is essentially the same in all its branches and varieties, so that the evolution of a new art form, a new gadget, a new scientific principle, all involve common factors. We are most interested in the “creation” of a new scientific principle or a new application of an old one, but we can be general here.

One way of investigating the problem is to consider the great ideas of the past and see just how they were generated. Unfortunately, the method of generation is never clear even to the “generators” themselves.

But what if the same earth-shaking idea occurred to two men, simultaneously and independently? Perhaps, the common factors involved would be illuminating. Consider the theory of evolution by natural selection, independently created by Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace.

There is a great deal in common there. Both traveled to far places, observing strange species of plants and animals and the manner in which they varied from place to place. Both were keenly interested in finding an explanation for this, and both failed until each happened to read Malthus’s “Essay on Population.”

Both then saw how the notion of overpopulation and weeding out (which Malthus had applied to human beings) would fit into the doctrine of evolution by natural selection (if applied to species generally).

Obviously, then, what is needed is not only people with a good background in a particular field, but also people capable of making a connection between item 1 and item 2 which might not ordinarily seem connected.

Undoubtedly in the first half of the 19th century, a great many naturalists had studied the manner in which species were differentiated among themselves. A great many people had read Malthus. Perhaps some both studied species and read Malthus. But what you needed was someone who studied species, read Malthus, and had the ability to make a cross-connection.

That is the crucial point that is the rare characteristic that must be found. Once the cross-connection is made, it becomes obvious. Thomas H. Huxley is supposed to have exclaimed after reading On the Origin of Species, “How stupid of me not to have thought of this.”

But why didn’t he think of it? The history of human thought would make it seem that there is difficulty in thinking of an idea even when all the facts are on the table. Making the cross-connection requires a certain daring. It must, for any cross-connection that does not require daring is performed at once by many and develops not as a “new idea,” but as a mere “corollary of an old idea.”

It is only afterward that a new idea seems reasonable. To begin with, it usually seems unreasonable. It seems the height of unreason to suppose the earth was round instead of flat, or that it moved instead of the sun, or that objects required a force to stop them when in motion, instead of a force to keep them moving, and so on.

A person willing to fly in the face of reason, authority, and common sense must be a person of considerable self-assurance. Since he occurs only rarely, he must seem eccentric (in at least that respect) to the rest of us. A person eccentric in one respect is often eccentric in others.

Consequently, the person who is most likely to get new ideas is a person of good background in the field of interest and one who is unconventional in his habits. (To be a crackpot is not, however, enough in itself.)

Once you have the people you want, the next question is: Do you want to bring them together so that they may discuss the problem mutually, or should you inform each of the problem and allow them to work in isolation?

My feeling is that as far as creativity is concerned, isolation is required. The creative person is, in any case, continually working at it. His mind is shuffling his information at all times, even when he is not conscious of it. (The famous example of Kekule working out the structure of benzene in his sleep is well-known.)

The presence of others can only inhibit this process, since creation is embarrassing. For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display.

Nevertheless, a meeting of such people may be desirable for reasons other than the act of creation itself.

Read the entire article here.