We know that social media helps us stay superficially connected to others. We also know many of the drawbacks — an over-inflated and skewed sense of self; poor understanding and reduced thoughtfulness; neurotic fear of missing out (FOMO); public shaming, online bullying and trolling.

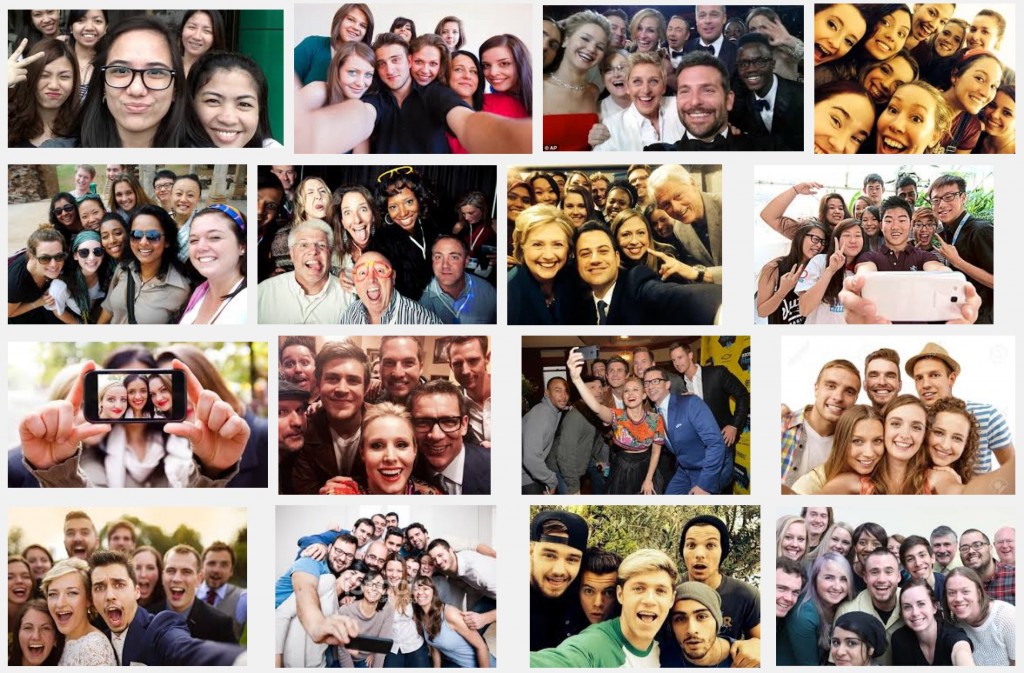

But, now we hear that one of the key foundations of social media — the taking and sharing of selfies — has more serious consequences. Social media has caused an explosion in head lice, especially in teenagers, particularly girls. Call it: social media head lice syndrome. While this may cause you to scratch your head in disbelief, or for psychosomatic reasons, the outbreak of lice is rather obvious. It goes like this: a group of teens needs a quick selfie fix; teens crowd around the smartphone and pose; teens lean in, heads together; head lice jump from one scalp to the next.

From the Independent:

Selfies have sparked an explosion in the number of head lice cases among teenagers a group of US paediatricians has warned.

The group said there is a growing trend of “social media lice” where lice spread![]() when teenagers cram their heads together to take a selfie.

when teenagers cram their heads together to take a selfie.

Lice cannot jump so they are less common in older children who do not tend to swap hats or headgear.

A Wisconsin paediatrician, Dr Sharon Rink, told local news channel WBAY2 she has seen a surge of teenagers coming to see her for treatment, something which was unheard of five years ago.

Dr Rink said: “People are doing selfies like every day, as opposed to going to photo booths years and years ago.

“So you’re probably having much more contact with other people’s heads.

“If you have an extremely itchy scalp and you’re a teenager, you might want to get checked out for lice instead of chalking it up to dandruff.”

In its official online guide to preventing the spread of head lice, the Center for Disease Control recommends avoiding head-to-head contact where possible and suggests girls are more likely to get the parasite than boys because they tend to have “more frequent head-to-head contact”.

Read (and scratch) more here.

Image courtesy of Google Search.

Research shows how children as young as four years empathize with some but not others. It’s all about the group: which peer group you belong to versus the rest. Thus, the uphill struggle to instill tolerance in the next generation needs to begin very early in life.

Research shows how children as young as four years empathize with some but not others. It’s all about the group: which peer group you belong to versus the rest. Thus, the uphill struggle to instill tolerance in the next generation needs to begin very early in life.