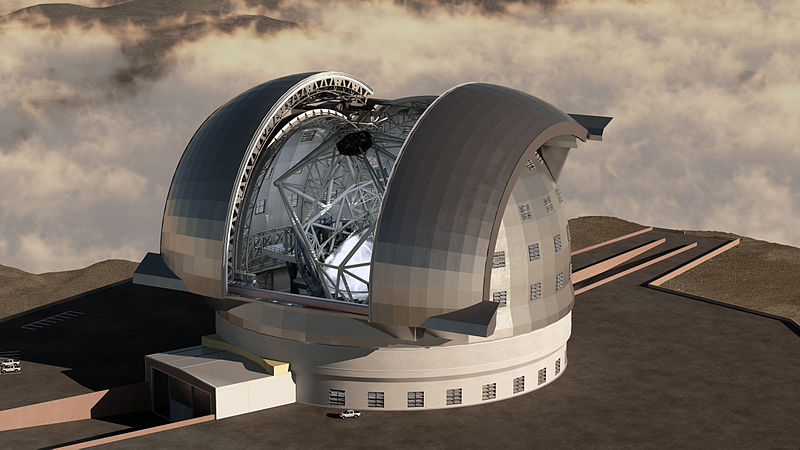

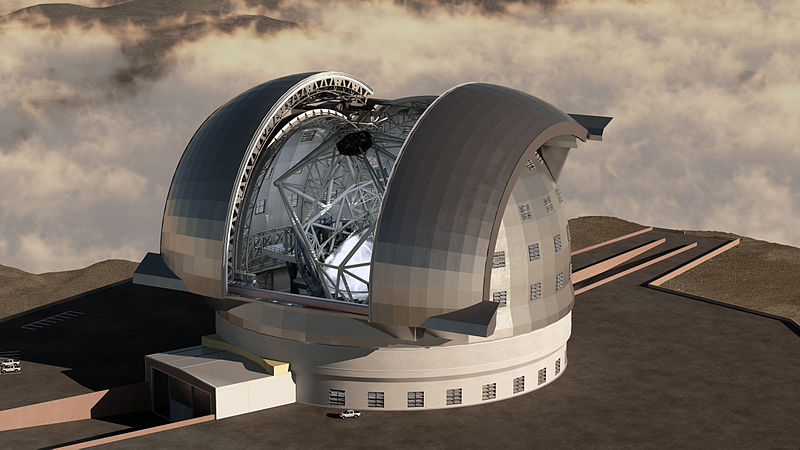

When it is cited in the high mountains in the Chilean coastal desert the European Extremely Large Telescope (or E-ELT) will be the biggest and the baddest telescope to date. With a mirror having a diameter of around 125 feet, the E-ELT will give observers unprecedented access to the vast panoramas of the cosmos. Astronomers are even confident that when it is fully operational, in about 2030, the telescope will be able to observe exo-planets directly, for the first time.

From the Observer:

Cerro Armazones is a crumbling dome of rock that dominates the parched peaks of the Chilean Coast Range north of Santiago. A couple of old concrete platforms and some rusty pipes, parts of the mountain’s old weather station, are the only hints that humans have ever taken an interest in this forbidding, arid place. Even the views look alien, with the surrounding boulder-strewn desert bearing a remarkable resemblance to the landscape of Mars.

Dramatic change is coming to Cerro Armazones, however – for in a few weeks, the 10,000ft mountain is going to have its top knocked off. “We are going to blast it with dynamite and then carry off the rubble,” says engineer Gird Hudepohl. “We will take about 80ft off the top of the mountain to create a plateau – and when we have done that, we will build the world’s biggest telescope there.”

Given the peak’s remote, inhospitable location that might sound an improbable claim – except for the fact that Hudepohl has done this sort of thing before. He is one of the European Southern Observatory’s most experienced engineers and was involved in the decapitation of another nearby mountain, Cerro Paranal, on which his team then erected one of the planet’s most sophisticated observatories.

The Paranal complex has been in operation for more than a decade and includes four giant instruments with eight-metre-wide mirrors – known as the Very Large Telescopes or VLTs – as well as control rooms and a labyrinth of underground tunnels linking its instruments. More than 100 astronomers, engineers and support staff work and live there. A few dozen metres below the telescopes, they have a sports complex with a squash court, an indoor football pitch, and a luxurious 110-room residence that has a central swimming pool and a restaurant serving meals and drinks around the clock. Built overlooking one of the world’s driest deserts, the place is an amazing oasis. (See box.)

Now the European Southern Observatory, of which Britain is a key member state, wants Hudepohl and his team to repeat this remarkable trick and take the top off Cerro Armazones, which is 20km distant. Though this time they will construct an instrument so huge it will dwarf all the telescopes on Paranal put together, and any other telescope on the planet. When completed, the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) and its 39-metre mirror will allow astronomers to peer further into space and look further back into the history of the universe than any other astronomical device in existence. Its construction will push telescope-making to its limit, however. Its primary mirror will be made of almost 800 segments – each 1.4 metres in diameter but only a few centimetres thick – which will have to be aligned with microscopic precision.

It is a remarkable juxtaposition: in the midst of utter desolation, scientists have built giant machines engineered to operate with smooth perfection and are now planning to top this achievement by building an even more vast device. The question is: for what purpose? Why go to a remote wilderness in northern Chile and chop down peaks to make homes for some of the planet’s most complex scientific hardware?

The answer is straightforward, says Cambridge University astronomer Professor Gerry Gilmore. It is all about water. “The atmosphere here is as dry as you can get and that is critically important. Water molecules obscure the view from telescopes on the ground. It is like trying to peer through mist – for mist is essentially a suspension of water molecules in the air, after all, and they obscure your vision. For a telescope based at sea level that is a major drawback.

“However, if you build your telescope where the atmosphere above you is completely dry, you will get the best possible views of the stars – and there is nowhere on Earth that has air drier than this place. For good measure, the high-altitude winds blow in a smooth, laminar manner above Paranal – like slabs of glass – so images of stars remain remarkably steady as well.”

The view of the heavens here is close to perfect, in other words – as an evening stroll around the viewing platform on Paranal demonstrates vividly. During my visit, the Milky Way hung over the observatory like a single white sheet. I could see the four main stars of the Southern Cross; Alpha Centauri, whose unseen companion Proxima Centauri is the closest star to our solar system; the two Magellanic Clouds, satellite galaxies of our own Milky Way; and the Coalsack, an interstellar dust cloud that forms a striking silhouette against the starry Milky Way. None are visible in northern skies and none appear with such brilliance anywhere else on the planet.

Hence the decision to build this extraordinary complex of VLTs. At sunset, each one’s housing is opened and the four great telescopes are brought slowly into operation. Each machine is made to rotate and swivel, like football players stretching muscles before a match. Each housing is the size of a block of flats. Yet they move in complete silence, so precise is their engineering.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Architectural rendering of ESO’s planned European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) shows the telescope at work, with its dome open and its record-setting 42-metre primary mirror pointed to the sky. Courtesy of the European Southern Observatory (ESO) / Wikipedia.