What audacity! A ten year journey, covering 4 billion miles.

On November 12, 2014 at 16:03 UTC, the Rosetta spacecraft delivered the Philae probe to land on a comet; a comet the size of New York’s Manhattan Island, speeding through our solar system at 34,000 miles per hour. What utter audacity!

The team of scientists, engineers, and theoreticians at the European Space Agency (ESA), and its partners, pulled off an awe-inspiring, remarkable and historic feat; a feat that ranks with the other pinnacles of human endeavor and exploration. It shows what our fledgling species can truly achieve.

Sadly, our species is flawed, capable of such terrible atrocities to ourselves and to our planet. And yet, triumphant stories like this one — the search for fundamental understanding through science — must give us all some continued hope.

Exploration. Inspiration. Daring. Risk. Execution. Discovery. Audacity!

From the Guardian:

These could be the dying hours of Philae, the device the size of a washing machine which travelled 4bn miles to hitch a ride on a comet. Philae is the “lander” which on Wednesday sprung from the craft that had carried it into deep, dark space, bounced a couple of times on the comet’s surface, and eventually found itself lodged in the shadows, starved of the sunlight its solar batteries needed to live. Yesterday, the scientists who had been planning this voyage for the past quarter-century sat and waited for word from their little explorer, hoping against hope that it still had enough energy to reveal its discoveries.

If Philae expires on the hard, rocky surface of Comet 67P the sadness will be felt far beyond mission control in Darmstadt, Germany. Indeed, it may be felt there least of all: those who have dedicated their working lives to this project pronounced it a success, regardless of a landing that didn’t quite go to plan (Philae’s anchor harpoons didn’t fire, so with gravity feeble there was nothing to keep the machine anchored to the original, optimal landing site). They were delighted to have got there at all and thrilled at Philae’s early work. Up to 90% of the science they planned to carry out has been done. As one scientist put it, “We’ve already got fantastic data.”

Those who lacked their expertise couldn’t help feel a pang all the same. The human instinct to anthropomorphise does not confine itself to cute animals, as anyone who has seen the film Wall-E can testify. If Pixar could make us well up for a waste-disposing robot, it’s little wonder the European Space Agency has had us empathising with a lander ejected from its “mothership”, identifiable only by its “spindly leg”. In those nervous hours, many will have been rooting for Philae, imagining it on that cold, hard surface yearning for sunlight, its beeps of data slowly petering out as its strength faded.

But that barely accounts for the fascination this adventure has stirred. Part of it is simple, a break from the torments down here on earth. You don’t have to go as far as Christopher Nolan film Interstellar, which fantasises about leaving our broken, ravaged planet and starting somewhere else – to enjoy a rare respite from our earthly woes. For a few merciful days, the news has featured a story remote from the bloodshed of Islamic State and Ukraine, from the pain of child abuse and poverty. Even those who don’t dream of escaping this planet can relish the escapism.

But the comet landing has provided more than a diversion: it’s been an antidote too. For this has been a story of human cooperation in a world of conflict. The narrow version of this point focuses on this as a European success story. When our daily news sees “Europe” only as the source of unwanted migrants or maddening regulation, Philae has offered an alternative vision; that Germany, Italy, France, Britain and others can achieve far more together than they could ever dream of alone. The geopolitical experts so often speak of the global pivot to Asia, the rise of the Bric nations and the like – but this extraordinary voyage has proved that Europe is not dead yet.

Even that, as I say, is to view it too narrowly. The US, through Nasa, is involved as well. And note the language attached to the hardware: the Rosetta satellite, the Ptolemy measuring instrument, the Osiris on-board camera, Philea itself – all imagery drawn from ancient Egypt. The spacecraft was named after the Rosetta stone, the discovery that unlocked hieroglyphics, as if to suggest a similar, if not greater, ambition: to decode the secrets of the universe. By evoking humankind’s ancient past, this is presented as a mission of the entire human race. There will be no flag planting on Comet 67P. As the Open University’s Jessica Hughes puts it, Philea, Rosetta and the rest “have become distant representatives of our shared, earthly heritage”.

That fits because this is how we experience such a moment: as a human triumph. When we marvel at the numbers – a probe has travelled for 10 years, crossed those 4bn miles, landed on a comet speeding at 34,000mph and done so within two minutes of its planned arrival – we marvel at what our species is capable of. I can barely get past the communication: that Darmstadt is able to contact an object 300 million miles away, sending instructions, receiving pictures. I can’t get phone reception in my kitchen, yet the ESA can be in touch with a robot that lies far beyond Mars. Like watching Usain Bolt run or hearing Maria Callas sing, we find joy and exhilaration in the outer limits of human excellence.

And of course we feel awe. What Interstellar prompts us to feel artificially – making us gasp at the confected scale and digitally assisted magnitude – Philae gives us for real. It is the stretch of time and place, glimpsing somewhere so far away it is as out of reach as ancient Egypt.

All that is before you reckon with the voyage’s scholarly purpose. “We are on the cutting edge of science,” they say, and of course they are. They are probing the deepest mysteries, including the riddle of how life began. (One theory suggests a comet brought water to a previously arid Earth.) What the authors of the Book of Genesis understood is that this question of origins is intimately bound up with the question of purpose. From the dawn of human time, to ask “How did we get here?” has been to ask “Why are we here?”

It’s why contemplation of the cosmic so soon reverts to the spiritual. Interstellar, like 2001: A Space Odyssey before it, is no different. It’s why one of the most powerful moments of Ronald Reagan’s presidency came when he paid tribute to the astronauts killed in the Challenger disaster. They had, he said, “slipped the surly bonds of Earth to touch the face of God”.

Not that you have to believe in such things to share the romance. Secularists, especially on the left, used to have a faith of their own. They believed that humanity was proceeding along an inexorable path of progress, that the world was getting better and better with each generation. The slaughter of the past century robbed them – us – of that once-certain conviction. Yet every now and again comes an unambiguous advance, what one ESA scientist called “A big step for human civilisation”. Even if we never hear from Philae again, we can delight in that.

Read the entire article here.

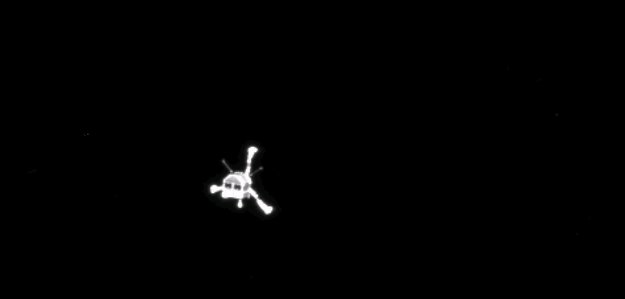

Image: Philae lander, detached from the Rosetta spacecraft, on its solitary journey towards the surface of comet P67. Courtesy of ESA.