Secular ideologues in the West believe they are on the moral high-ground. The separation of church (and mosque or synagogue) from state is, they believe, the path to a more just, equal and less-violent culture. They will cite example after example in contemporary and recent culture of terrible violence in the name of religious extremism and fundamentalism.

And, yet, step back for a minute from the horrendous stories and images of atrocities wrought by religious fanatics in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Think of the recent histories of fledgling nations in Africa; the ethnic cleansings across much of Central and Eastern Europe — several times over; the egomaniacal tribal terrorists of Central Asia, the brutality of neo-fascists and their socialist bedfellows in Latin America. Delve deeper into these tragic histories — some still unfolding before our very eyes — and you will see a much more complex view of humanity. Our tribal rivalries know no bounds and our violence towards others is certainly not limited only to the catalyst of religion. Yes, we fight for our religion, but we also fight for territory, politics, resources, nationalism, revenge, poverty, ego. Soon the coming fights will be about water and food — these will make our wars over belief systems seem rather petty.

Scholar and author Karen Armstrong explores the complexities of religious and secular violence in the broader context of human struggle in her new book, Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence.

From the Guardian:

As we watch the fighters of the Islamic State (Isis) rampaging through the Middle East, tearing apart the modern nation-states of Syria and Iraq created by departing European colonialists, it may be difficult to believe we are living in the 21st century. The sight of throngs of terrified refugees and the savage and indiscriminate violence is all too reminiscent of barbarian tribes sweeping away the Roman empire, or the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan cutting a swath through China, Anatolia, Russia and eastern Europe, devastating entire cities and massacring their inhabitants. Only the wearily familiar pictures of bombs falling yet again on Middle Eastern cities and towns – this time dropped by the United States and a few Arab allies – and the gloomy predictions that this may become another Vietnam, remind us that this is indeed a very modern war.

The ferocious cruelty of these jihadist fighters, quoting the Qur’an as they behead their hapless victims, raises another distinctly modern concern: the connection between religion and violence. The atrocities of Isis would seem to prove that Sam Harris, one of the loudest voices of the “New Atheism”, was right to claim that “most Muslims are utterly deranged by their religious faith”, and to conclude that “religion itself produces a perverse solidarity that we must find some way to undercut”. Many will agree with Richard Dawkins, who wrote in The God Delusion that “only religious faith is a strong enough force to motivate such utter madness in otherwise sane and decent people”. Even those who find these statements too extreme may still believe, instinctively, that there is a violent essence inherent in religion, which inevitably radicalises any conflict – because once combatants are convinced that God is on their side, compromise becomes impossible and cruelty knows no bounds.

Despite the valiant attempts by Barack Obama and David Cameron to insist that the lawless violence of Isis has nothing to do with Islam, many will disagree. They may also feel exasperated. In the west, we learned from bitter experience that the fanatical bigotry which religion seems always to unleash can only be contained by the creation of a liberal state that separates politics and religion. Never again, we believed, would these intolerant passions be allowed to intrude on political life. But why, oh why, have Muslims found it impossible to arrive at this logicalsolution to their current problems? Why do they cling with perverse obstinacy to the obviously bad idea of theocracy? Why, in short, have they been unable to enter the modern world? The answer must surely lie in their primitive and atavistic religion.

But perhaps we should ask, instead, how it came about that we in the west developed our view of religion as a purely private pursuit, essentially separate from all other human activities, and especially distinct from politics. After all, warfare and violence have always been a feature of political life, and yet we alone drew the conclusion that separating the church from the state was a prerequisite for peace. Secularism has become so natural to us that we assume it emerged organically, as a necessary condition of any society’s progress into modernity. Yet it was in fact a distinct creation, which arose as a result of a peculiar concatenation of historical circumstances; we may be mistaken to assume that it would evolve in the same fashion in every culture in every part of the world.

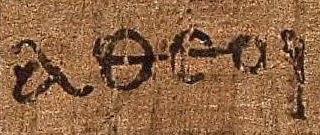

We now take the secular state so much for granted that it is hard for us to appreciate its novelty, since before the modern period, there were no “secular” institutions and no “secular” states in our sense of the word. Their creation required the development of an entirely different understanding of religion, one that was unique to the modern west. No other culture has had anything remotely like it, and before the 18th century, it would have been incomprehensible even to European Catholics. The words in other languages that we translate as “religion” invariably refer to something vaguer, larger and more inclusive. The Arabic word dinsignifies an entire way of life, and the Sanskrit dharma covers law, politics, and social institutions as well as piety. The Hebrew Bible has no abstract concept of “religion”; and the Talmudic rabbis would have found it impossible to define faith in a single word or formula, because the Talmud was expressly designed to bring the whole of human life into the ambit of the sacred. The Oxford Classical Dictionary firmly states: “No word in either Greek or Latin corresponds to the English ‘religion’ or ‘religious’.” In fact, the only tradition that satisfies the modern western criterion of religion as a purely private pursuit is Protestant Christianity, which, like our western view of “religion”, was also a creation of the early modern period.

Traditional spirituality did not urge people to retreat from political activity. The prophets of Israel had harsh words for those who assiduously observed the temple rituals but neglected the plight of the poor and oppressed. Jesus’s famous maxim to “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” was not a plea for the separation of religion and politics. Nearly all the uprisings against Rome in first-century Palestine were inspired by the conviction that the Land of Israel and its produce belonged to God, so that there was, therefore, precious little to “give back” to Caesar. When Jesus overturned the money-changers’ tables in the temple, he was not demanding a more spiritualised religion. For 500 years, the temple had been an instrument of imperial control and the tribute for Rome was stored there. Hence for Jesus it was a “den of thieves”. The bedrock message of the Qur’an is that it is wrong to build a private fortune but good to share your wealth in order to create a just, egalitarian and decent society. Gandhi would have agreed that these were matters of sacred import: “Those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means.”

The myth of religious violence

Before the modern period, religion was not a separate activity, hermetically sealed off from all others; rather, it permeated all human undertakings, including economics, state-building, politics and warfare. Before 1700, it would have been impossible for people to say where, for example, “politics” ended and “religion” began. The Crusades were certainly inspired by religious passion but they were also deeply political: Pope Urban II let the knights of Christendom loose on the Muslim world to extend the power of the church eastwards and create a papal monarchy that would control Christian Europe. The Spanish inquisition was a deeply flawed attempt to secure the internal order of Spain after a divisive civil war, at a time when the nation feared an imminent attack by the Ottoman empire. Similarly, the European wars of religion and the thirty years war were certainly exacerbated by the sectarian quarrels of Protestants and Catholics, but their violence reflected the birth pangs of the modern nation-state.

Read the entire article here.

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,

Alain de Botton is a writer of book-length essays on love, travel, architecture and literature. In his latest book,  [div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The Stone forum, New York Times:[end-div]