Forget wearable electronics, like Google Glass. That’s so, well, 2012. Welcome to the new world of epidermal electronics — electronic tattoos that contain circuits and sensors printed directly on to the body.

Forget wearable electronics, like Google Glass. That’s so, well, 2012. Welcome to the new world of epidermal electronics — electronic tattoos that contain circuits and sensors printed directly on to the body.

From MIT Technology Review:

Taking advantage of recent advances in flexible electronics, researchers have devised a way to “print” devices directly onto the skin so people can wear them for an extended period while performing normal daily activities. Such systems could be used to track health and monitor healing near the skin’s surface, as in the case of surgical wounds.

So-called “epidermal electronics” were demonstrated previously in research from the lab of John Rogers, a materials scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; the devices consist of ultrathin electrodes, electronics, sensors, and wireless power and communication systems. In theory, they could attach to the skin and record and transmit electrophysiological measurements for medical purposes. These early versions of the technology, which were designed to be applied to a thin, soft elastomer backing, were “fine for an office environment,” says Rogers, “but if you wanted to go swimming or take a shower they weren’t able to hold up.” Now, Rogers and his coworkers have figured out how to print the electronics right on the skin, making the device more durable and rugged.

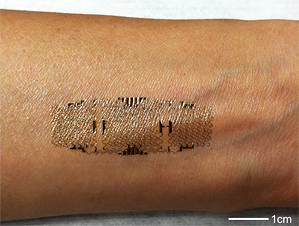

“What we’ve found is that you don’t even need the elastomer backing,” Rogers says. “You can use a rubber stamp to just deliver the ultrathin mesh electronics directly to the surface of the skin.” The researchers also found that they could use commercially available “spray-on bandage” products to add a thin protective layer and bond the system to the skin in a “very robust way,” he says.

Eliminating the elastomer backing makes the device one-thirtieth as thick, and thus “more conformal to the kind of roughness that’s present naturally on the surface of the skin,” says Rogers. It can be worn for up to two weeks before the skin’s natural exfoliation process causes it to flake off.

During the two weeks that it’s attached, the device can measure things like temperature, strain, and the hydration state of the skin, all of which are useful in tracking general health and wellness. One specific application could be to monitor wound healing: if a doctor or nurse attached the system near a surgical wound before the patient left the hospital, it could take measurements and transmit the information wirelessly to the health-care providers.

Read the entire article after the jump.

Image: Epidermal electronic snesor printed on the skin. Courtesy of MIT.

[div class=attrib]From Anthropology in Practice:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Anthropology in Practice:[end-div]