Now that almost two weeks have gone by since Christmas it’s time to reflect on it’s (historical) meaning beyond the shopping discounts, santa hats and incessant cheesy music.

We know that Christmas falls on two different dates depending on whether you follow the Gregorian or Julian (orthodox) calendars.

We know that many Christmas traditions were poached and re-purposed from rituals and traditions that predate the birth of Jesus, regardless of which calendar you adhere to: the 12-days of Christmas (christmastide) originated from the ancient Germanic mid-winter, more recently Norse, festival of Yule; the tradition of gift giving and partying came from the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia; the Western Christian church settled on December 25 based on the ancient Roman date of the winter solstice; holiday lights came from the ancient pagans who lit bonfires and candles on the winter solstice to celebrate the return of the light.

And, let’s not forget the now ubiquitous westernized Santa Claus. We know that Santa has evolved over the centuries from a melting pot of European traditions including those surrounding Saint Nicolas, who was born to a Greek family in Asia Minor (Greek Anatolia in present-day Turkey), and the white-bearded Norse god, Odin.

So, what of Jesus? We know that the gospels describing him are contradictory, written by different, anonymous and usually biased authors, and at different times, often decades after the reported fact. We have no eye-witness accounts. We lack a complete record — there is no account for Jesus’ years 12-30. Indeed, religion aside, many scholars, now question the historic existence of Jesus, the man.

From Big Think:

Today, several books approach the subject, including Zealot by Reza Aslan, Nailed: Ten Christian Myths That Show Jesus Never Existed at All by David Fitzgerald, and How Jesus Became God by Bart Ehrman. Historian Richard Carrier in his 600 page monograph: On the Historicity of Jesus, writes that the story may have derived from earlier semi-divine beings from Near East myth, who were murdered by demons in the celestial realm. This would develop over time into the gospels, he said. Another theory is that Jesus was a historical figure who become mythicized later on.

Carrier believes the pieces added to the work of Josephus were done by Christian scribes. In one particular passage, Carrier says that the execution by Pilate of Jesus was obviously lifted from the Gospel of Luke. Similar problems such as miscopying and misrepresentations are found throughout Tacitus. So where do all the stories in the New Testament derive? According to Carrier, Jesus may be as much a mythical figure as Hercules or Oedipus.

Ehrman focuses on the lack of witnesses. “What sorts of things do pagan authors from the time of Jesus have to say about him? Nothing. As odd as it may seem, there is no mention of Jesus at all by any of his pagan contemporaries. There are no birth records, no trial transcripts, no death certificates; there are no expressions of interest, no heated slanders, no passing references – nothing.”

…

One biblical scholar holds an even more radical idea, that Jesus story was an early form of psychological warfare to help quell a violent insurgency. The Great Revolt against Rome occurred in 66 BCE. Fierce Jewish warriors known as the Zealots won two decisive victories early on. But Rome returned with 60,000 heavily armed troops. What resulted was a bloody war of attrition that raged for three decades.

Atwill contends that the Zealots were awaiting the arrival of a warrior messiah to throw off the interlopers. Knowing this, the Roman court under Titus Flavius decided to create their own, competing messiah who promoted pacifism among the populous. According to Atwill, the story of Jesus was taken from many sources, including the campaigns of a previous Caesar.

Of course, there may very well have been a Rabbi Yeshua ben Yosef (as would have been Jesus’s real name) who gathered a flock around his teachings in the first century. Most antiquarians believe a real man existed and became mythicized. But the historical record itself is thin.

Read the entire article here.

Image: “Merry Old Santa Claus”, by Thomas Nast, January 1, 1881 edition of Harper’s Weekly. Public Domain.

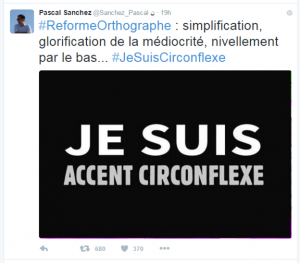

The French have a formal language police.

The French have a formal language police.