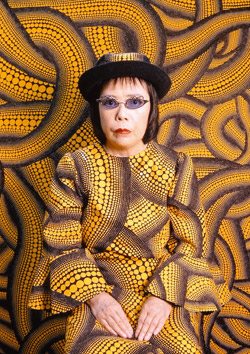

Yayoi Kusama, c1939 Yayoi Kusama, 2000

The art establishment has Yayoi Kusama in its sights, again. Over the last 60 years Kusama has created and evolved a style that is all her own, best seen rather than discussed.

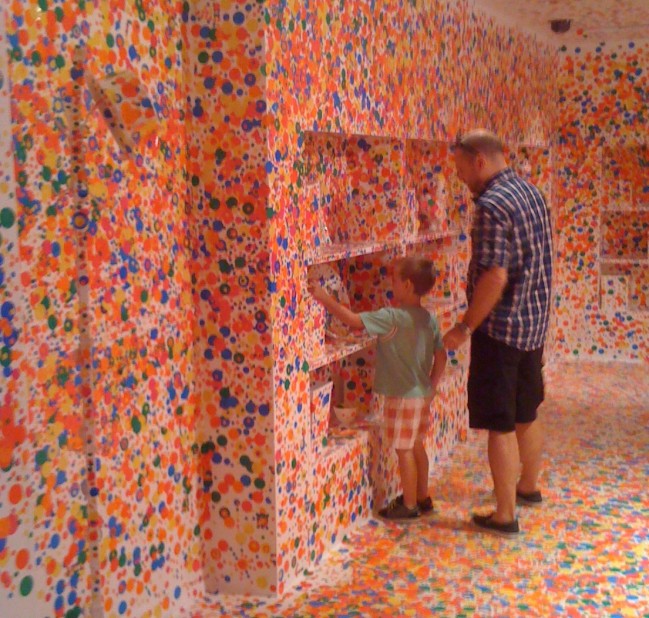

A recent exhibit of Kusama’s work in Brisbane featured “The obliteration room”. This wonderful, interactive exhibit was commissioned specifically for kids aged 1-101 years. The exhibit features a whitewashed room with simple furniture, fixtures and objects all in white. The interactive — and fun — part features sheets of bright and colorful sticky dots given to each visitor. Armed with these dots visitors are encouraged to place them anywhere and everywhere. Results below (including a few, select dots courtesy of theDiagonal’s editor).

For an interesting timeline of her work, courtesy of the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, Australia follow this jump.

[div class=attrib]From the Telegraph:[end-div]

There are spots before my eyes. I am at the National Museum of Art in Osaka, Japan, where crowds are flocking to a big exhibition of Yayoi Kusama’s work. Dots are a recurring theme in her art, a visual representation of the hallucinations and anxiety attacks she has suffered from since childhood, so the show is dominated by giant red polka-dotted spheres, and a disorienting room in which huge white fibreglass tulips are covered in red dots – as are the white walls, ceiling and floor.

There’s one of her unsettling infinity mirror rooms, illuminated by seemingly endless floating dots of light, and a giant pumpkin crawling with a distinctive pattern of dots she calls Nerves. But unlike her retrospective at Tate Modern in London, which ran from February to June this year, the emphasis here is on her recent paintings: one long gallery is filled with monochrome works, another with paintings so bright they hurt the eyes. The same primitive, repetitive motifs occur in all of them: dots, eyes, faces, zigzag patterns, amoebic blobs and snakelike forms bristling with cilia.

The sheer number is overwhelming, dizzying. When she was based in New York, her phallus sculptures and naked hippie ‘happenings’ were seen as scandalous and shameful by many in her home country, but the scale of this show is an indication of her standing in Japan, where she is fast becoming a national treasure.

The next day, I am invited to Kusama’s studio in a backstreet of the Shinjuku area of Tokyo, a short walk away from her private room in Siewa Hospital, a psychiatric unit where she has been a voluntary in-patient since 1977 and which she rarely leaves, except to work. Her studio is a cramped concrete and glass building, with cardboard boxes of supplies stacked up to the ceiling, the walls covered in racks of finished paintings, works in progress and blank canvases, a grey paint-spattered industrial carpet and a scruffy old office chair at the table where Kusama works under a glaring neon strip light.

She usually paints in comfortable pyjamas, one of her assistants tells me, her grey hair pulled up into a bun, but today she is upstairs having her hair and make-up done, ready to greet her guests.

When she finally comes down in the lift, a frail but colourful 83-year-old resplendent in a red wig and polka-dot ensemble, pushed in a polka-dotted wheelchair, she asks an assistant to show us some press cuttings of the Tate show, especially one from a paper from Matsumoto City, where she grew up. There’s something touching about this need to prove herself, but it’s also confusing – akin to J K Rowling showing off a review in The Gloucestershire Echo to verify that she is a published author.

Talking to Kusama can be a surreal experience. She is easily distracted, and although she lived in America for 20 years, she now speaks no English. She is surrounded by a team of assistants who translate for her, addressing her with respect as ‘sensei’ (‘master’ or ‘teacher’), and with whom she often seems to have long discussions before answering even the blandest questions. It’s hard to know what is being lost in translation, and what is down to the vagaries of age and health. But occasionally a question will engage her, and you’ll get a brief but fierce flash of the intelligence and focus she has so clearly poured into her work over the years.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Images: Yayoi Kusama, 1939 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc; Kusama, 2000 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc; theDiagonal / Queensland Art Gallery.[end-div]