Gary Gutting, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us that work is punishment for Adam’s sin, according to the Book of Genesis. No doubt, many who hold other faiths, as well as those who don’t, may tend to agree with this basic notion.

Gary Gutting, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us that work is punishment for Adam’s sin, according to the Book of Genesis. No doubt, many who hold other faiths, as well as those who don’t, may tend to agree with this basic notion.

So, what on earth is work for?

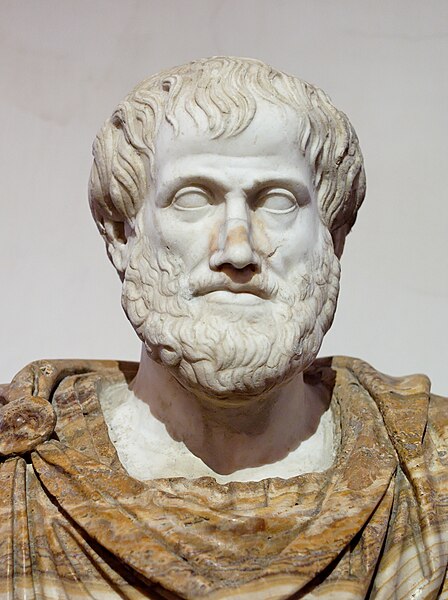

Gutting goes on to remind us that Aristotle and Bertrand Russell had it right: that work is for the sake of leisure.

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

Is work good or bad? A fatuous question, it may seem, with unemployment such a pressing national concern. (Apart from the names of the two candidates, “jobs” was the politically relevant word most used by speakers at the Republican and Democratic conventions.) Even apart from current worries, the goodness of work is deep in our culture. We applaud people for their work ethic, judge our economy by its productivity and even honor work with a national holiday.

But there’s an underlying ambivalence: we celebrate Labor Day by not working, the Book of Genesis says work is punishment for Adam’s sin, and many of us count the days to the next vacation and see a contented retirement as the only reason for working.

We’re ambivalent about work because in our capitalist system it means work-for-pay (wage-labor), not for its own sake. It is what philosophers call an instrumental good, something valuable not in itself but for what we can use it to achieve. For most of us, a paying job is still utterly essential — as masses of unemployed people know all too well. But in our economic system, most of us inevitably see our work as a means to something else: it makes a living, but it doesn’t make a life.

What, then, is work for? Aristotle has a striking answer: “we work to have leisure, on which happiness depends.” This may at first seem absurd. How can we be happy just doing nothing, however sweetly (dolce far niente)? Doesn’t idleness lead to boredom, the life-destroying ennui portrayed in so many novels, at least since “Madame Bovary”?

Everything depends on how we understand leisure. Is it mere idleness, simply doing nothing? Then a life of leisure is at best boring (a lesson of Voltaire’s “Candide”), and at worst terrifying (leaving us, as Pascal says, with nothing to distract from the thought of death). No, the leisure Aristotle has in mind is productive activity enjoyed for its own sake, while work is done for something else.

We can pass by for now the question of just what activities are truly enjoyable for their own sake — perhaps eating and drinking, sports, love, adventure, art, contemplation? The point is that engaging in such activities — and sharing them with others — is what makes a good life. Leisure, not work, should be our primary goal.

Bertrand Russell, in his classic essay “In Praise of Idleness,” agrees. ”A great deal of harm,” he says, “is being done in the modern world by belief in the virtuousness of work.” Instead, “the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.” Before the technological breakthroughs of the last two centuries, leisure could be only “the prerogative of small privileged classes,” supported by slave labor or a near equivalent. But this is no longer necessary: “The morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Bust of Aristotle. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Lysippos from 330 BC; the alabaster mantle is a modern addition. Courtesy of Wikipedia.[end-div]