The average Facebook user is said to have 142 “friends”, and many active members have over 500. This certainly seems to be a textbook case of quantity over quality in the increasingly competitive status wars and popularity stakes of online neo- or pseudo-celebrity. That said, and regardless of your relationship with online social media, the one good to come from the likes — a small pun intended — of Facebook is that social scientists can now dissect and analyze your online behaviors and relationships as never before.

So, while Facebook, and its peers, may not represent a qualitative leap in human relationships the data and experiences that come from it may help future generations figure out what is truly important.

From the Wall Street Journal:

Facebook has made an indelible mark on my generation’s concept of friendship. The average Facebook user has 142 friends (many people I know have upward of 500). Without Facebook many of us “Millennials” wouldn’t know what our friends are up to or what their babies or boyfriends look like. We wouldn’t even remember their birthdays. Is this progress?

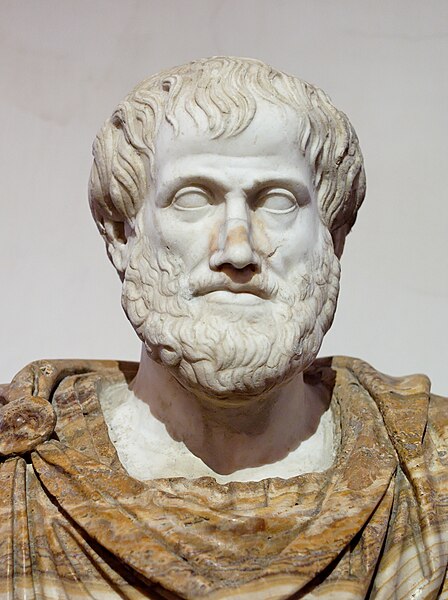

Aristotle wrote that friendship involves a degree of love. If we were to ask ourselves whether all of our Facebook friends were those we loved, we’d certainly answer that they’re not. These days, we devote equal if not more time to tracking the people we have had very limited human interaction with than to those whom we truly love. Aristotle would call the former “friendships of utility,” which, he wrote, are “for the commercially minded.”

I’d venture to guess that at least 90% of Facebook friendships are those of utility. Knowing this instinctively, we increasingly use Facebook as a vehicle for self-promotion rather than as a means to stay connected to those whom we love. Instead of sharing our lives, we compare and contrast them, based on carefully calculated posts, always striving to put our best face forward.

Friendship also, as Aristotle described it, can be based on pleasure. All of the comments, well-wishes and “likes” we can get from our numerous Facebook friends may give us pleasure. But something feels false about this. Aristotle wrote: “Those who love for the sake of pleasure do so for the sake of what is pleasant to themselves, and not insofar as the other is the person loved.” Few of us expect the dozens of Facebook friends who wish us a happy birthday ever to share a birthday celebration with us, let alone care for us when we’re sick or in need.

One thing’s for sure, my generation’s friendships are less personal than my parents’ or grandparents’ generation. Since we can rely on Facebook to manage our friendships, it’s easy to neglect more human forms of communication. Why visit a person, write a letter, deliver a card, or even pick up the phone when we can simply click a “like” button?

The ultimate form of friendship is described by Aristotle as “virtuous”—meaning the kind that involves a concern for our friend’s sake and not for our own. “Perfect friendship is the friendship of men who are good, and alike in virtue . . . . But it is natural that such friendships should be infrequent; for such men are rare.”

Those who came before the Millennial generation still say as much. My father and grandfather always told me that the number of such “true” friends can be counted on one hand over the course of a lifetime. Has Facebook increased our capacity for true friendship? I suspect Aristotle would say no.

Ms. Kelly joined Facebook in 2004 and quit in 2013.

Read the entire article here.

Gary Gutting, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us that work is punishment for Adam’s sin, according to the Book of Genesis. No doubt, many who hold other faiths, as well as those who don’t, may tend to agree with this basic notion.

Gary Gutting, professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us that work is punishment for Adam’s sin, according to the Book of Genesis. No doubt, many who hold other faiths, as well as those who don’t, may tend to agree with this basic notion.