Read the following article once and you could be forgiven for assuming that it’s a fictional screenplay for Hollywood’s next R-rated Halloween flick or perhaps the depraved tale of an associate of Nazi SS officer and physician Josef Mengele.

Read the following article twice and you’ll see that the story of neurologist Dr. Walter Freeman is true: the victims — patients — were military veterans numbering in the thousands, and it took place in the United States following WWII.

This awful story is all the more incomprehensible by virtue of the cadre of assistants, surgeons, psychiatrists, do-gooders and government bureaucrats who actively aided Freeman or did nothing to stop his foolish, amateurish experiments. Unbelievable!

From WSJ:

As World War II raged, two Veterans Administration doctors reported witnessing something extraordinary: An eminent neurologist, Walter J. Freeman, and his partner treating a mentally ill patient by cutting open the skull and slicing through neural fibers in the brain.

It was an operation Dr. Freeman called a lobotomy.

Their report landed on the desk of VA chief Frank Hines on July 26, 1943, in the form of a memo recommending lobotomies for veterans with intractable mental illnesses. The operation “may be done, in suitable cases, under local anesthesia,” the memo said. It “does not demand a high degree of surgical skill.”

The next day Mr. Hines stamped the memo in purple ink: APPROVED.

Over the next dozen or so years, the U.S. government would lobotomize roughly 2,000 American veterans, according to a cache of forgotten VA documents unearthed by The Wall Street Journal, including the memo approved by Mr. Hines. It was a decision made “in accord with our desire to keep abreast of all advances in treatment,” the memo said.

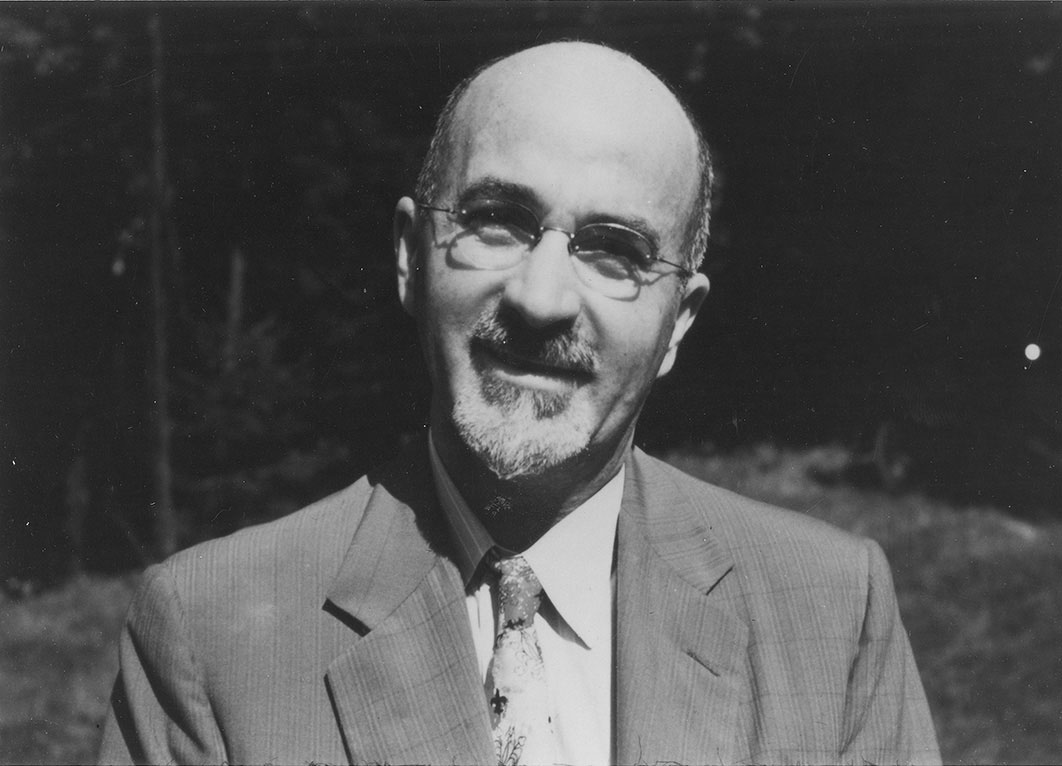

The 1943 decision gave birth to an alliance between the VA and lobotomy’s most dogged salesman, Dr. Freeman, a man famous in his day and notorious in retrospect. His prolific—some critics say reckless—use of brain surgery to treat mental illness places him today among the most controversial figures in American medical history.

At the VA, Dr. Freeman pushed the frontiers of ethically acceptable medicine. He said VA psychiatrists, untrained in surgery, should be allowed to perform lobotomies by hammering ice-pick-like tools through patients’ eye sockets. And he argued that, while their patients’ skulls were open anyway, VA surgeons should be permitted to remove samples of living brain for research purposes.

The agency’s use of lobotomy tailed off when the first major antipsychotic drug, Thorazine, came on the market in the mid-1950s, and public opinion of Dr. Freeman and his signature surgery pivoted from admiration to horror.

During and immediately after World War II, lobotomies weren’t greeted with the dismay they prompt today. Still, Dr. Freeman’s views sparked a heated debate inside the agency about the wisdom and ethics of an operation Dr. Freeman himself described as “a surgically induced childhood.”

In 1948, one senior VA psychiatrist wrote a memo mocking Dr. Freeman for using lobotomies to treat “practically everything from delinquency to a pain in the neck.” Other doctors urged more research before forging ahead with such a dramatic medical intervention. A number objected in particular to the Freeman ice-pick technique.

Yet Dr. Freeman’s influence proved decisive. The agency brought Dr. Freeman and his junior partner, neurosurgeon James Watts, aboard as consultants, speakers and inspirations, and its doctors performed lobotomies on veterans at some 50 hospitals from Massachusetts to Oregon.

Born in 1895 to a family of Philadelphia doctors, Yale-educated Dr. Freeman was drawn to psychosurgery by his work in the wards of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, where Washington’s mentally ill, including World War I veterans, were housed but rarely cured. The treatments of the day—psychotherapy, electroshock, high-pressure water sprays and insulin injections to induce temporary comas—wouldn’t successfully cure serious mental illnesses that resulted from physical defects in the brain, Dr. Freeman believed. His suggestion was to sever faulty neural pathways between the prefrontal area and the rest of the brain, channels believed by lobotomy practitioners to promote excessive emotions.

It was an approach pioneered by Egas Moniz, a Portuguese physician who in 1935 performed the first lobotomy (then called a leucotomy). Fourteen years later, he was rewarded with the Nobel Prize in medicine.

In 1936, Drs. Freeman and Watts performed their first lobotomy, on a 63-year-old woman suffering from depression, anxiety and insomnia. “I knew as soon as I operated on a mental patient and cut into a physically normal brain, I’d be considered radical by some people,” Dr. Watts said in a 1979 interview transcribed in the George Washington University archives.

By his own count, Dr. Freeman would eventually participate in 3,500 lobotomies, some, according to records in the university archives, on children as young as four years old.

“In my father’s hands, the operation worked,” says his son, Walter Freeman III, a retired professor of neurobiology. “This was an explanation for his zeal.”

Drs. Freeman and Watts considered about one-third of their operations successes in which the patient was able to lead a “productive life,” Dr. Freeman’s son says. Another third were able to return home but not support themselves. The final third were “failures,” according to Dr. Watts.

Later in life, Dr. Watts, who died in 1994, offered a blunt assessment of lobotomy’s heyday. “It’s a brain-damaging operation. It changes the personality,” he said in the 1979 interview. “We could predict relief, and we could fairly accurately predict relief of certain symptoms like suicidal ideas, attempts to kill oneself. We could predict there would be relief of anxiety and emotional tension. But we could not nearly as accurately predict what kind of person this was going to be.”

Other possible side-effects included seizures, incontinence, emotional outbursts and, on occasion, death.

Read the entire article here.