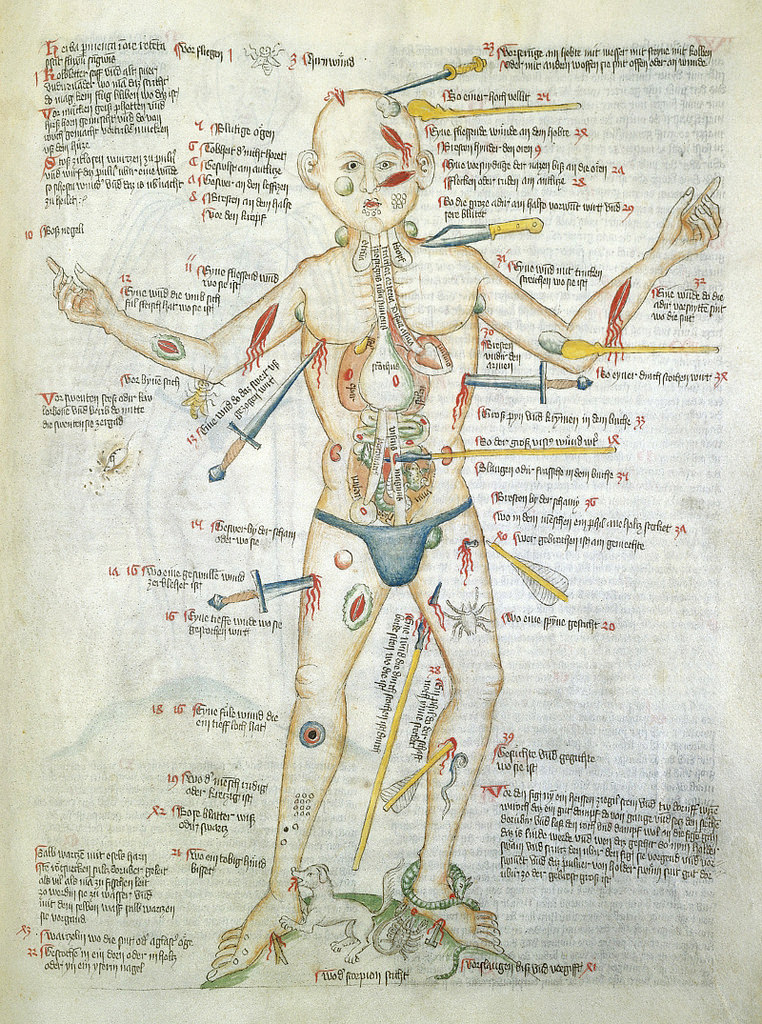

No, the image is not a still from a forthcoming episode of Law & Order or Criminal Minds. Nor is it a nightmarish Hieronymus Bosch artwork.

Rather, “Wound Man”, as he was known, is a visual table of contents to a medieval manuscript of medical cures, treatments and surgeries. Wound Man first appeared in German surgical texts in the early 15th century. Arranged around each of his various wounds and ailments are references to further details on appropriate treatments. For instance, reference number 38 alongside an arrow penetrating Wound Man’s thigh, “An arrow whose shaft is still in place”, leads to details on how to address the wound — presumably a relatively common occurrence in the Middle Ages.

From Public Domain Review:

Staring impassively out of the page, he bears a multitude of graphic wounds. His skin is covered in bleeding cuts and lesions, stabbed and sliced by knives, spears and swords of varying sizes, many of which remain in the skin, protruding porcupine-like from his body. Another dagger pierces his side, and through his strangely transparent chest we see its tip puncture his heart. His thighs are pierced with arrows, some intact, some snapped down to just their heads or shafts. A club slams into his shoulder, another into the side of his face.

His neck, armpits and groin sport rounded blue buboes, swollen glands suggesting that the figure has contracted plague. His shins and feet are pockmarked with clustered lacerations and thorn scratches, and he is beset by rabid animals. A dog, snake and scorpion bite at his ankles, a bee stings his elbow, and even inside the cavity of his stomach a toad aggravates his innards.

Despite this horrendous cumulative barrage of injuries, however, the Wound Man is very much alive. For the purpose of this image was not to threaten or inspire fear, but to herald potential cures for all of the depicted maladies. He contrarily represented something altogether more hopeful than his battered body: an arresting reminder of the powerful knowledge that could be channelled and dispensed in the practice of late medieval medicine.

The earliest known versions of the Wound Man appeared at the turn of the fifteenth century in books on the surgical craft, particularly works from southern Germany associated with the renowned Würzburg surgeon Ortolf von Baierland (died before 1339). Accompanying a text known as the “Wundarznei” (The Surgery), these first Wound Men effectively functioned as a human table of contents for the cures contained within the relevant treatise. Look closely at the remarkable Wound Man shown above from the Wellcome Library’s MS. 49 – a miscellany including medical material produced in Germany in about 1420 – and you see that the figure is penetrated not only by weapons but also by text.

Read the entire article here.

Image: The Wound Man. Courtesy: Wellcome Library’s MS. 49 — Source (CC BY 4.0). Public Domain Review.