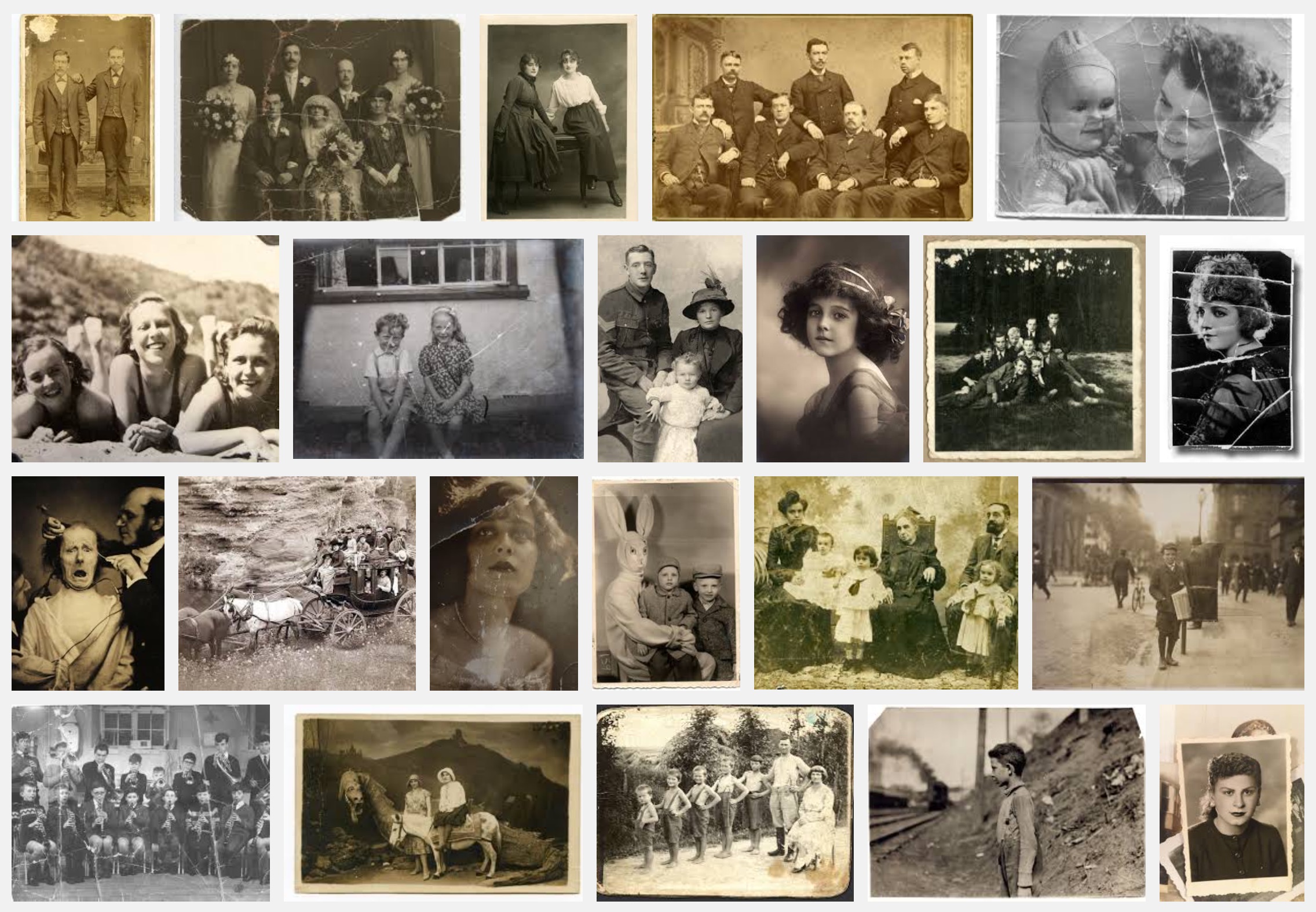

Chances are that when you are feeling sentimental or nostalgic you’ll head straight for the old photographs. If you’ve had the misfortune of being swept up in a natural or accidental disaster — fire, flood, hurricane — it’s likely that the objects you seek out first or miss the most while be your photographs. Those of us over the age of 35 may still have physical albums or piles of ancient images stored in shoeboxes or biscuit tins. And, like younger generations, we’ll also have countless pictures stored on our smartphones or computers or a third party internet service like Instagram or Pinterest — organized or not. We hold on to our physical and digital images because they carry meaning and store our connections. A timely article from Wired’s editor reminds us to keep even the bad ones.

From Wired:

The past 12 months sucked. Over that span I lost my grandmother, a childhood friend, and a colleague. Grief is a weak spring; if there’s not enough time between blows, you don’t bounce back. You just keep getting pushed down. Soon even a minor bummer could conjure deep sadness. I took comfort in photos: some dug out of boxes but most unearthed online.

One particularly low evening, I sat on the couch reading my departed friend’s blog. I’d read it before—beginning to end, a river that spanned years and documented her battle with illness. This time I just scanned for images. I sat there frozen. My wet face locked into the glow-cone of my laptop, captivated by an unexpected solace: candid photos.

The posed pictures didn’t do it for me; they felt like someone else, effigies at best. But in the side shots and reflections, the thumbnail in a screencapped FaceTime chat, I felt like I was really seeing her. It was as if those frames contained a forever-spark of her life.

“A posed image can never be the same as when someone’s guard is down.” So said Costa Sakellariou, a photography professor at Binghamton University whose course I took the summer of my second junior year. I enrolled in it to make up credits that I was too busy getting wasted to accrue during the regular academic year (helluva student, this guy), but the experience ended up being really important to me.

Costa would have us use manual film cameras for street photography. We’d set our aperture to a daylight-friendly f/16, prefocus at 3 feet, then go downtown to ambush pedestrians. “A candid photograph captures the intersections of life,” he’d say. Well, he said something like that back then, but he said exactly that when I called him to talk for the first time in 15 years.

He’s still at Binghamton, his students still shoot film (mostly), and he’s not super-sanguine about the direction photography is taking. It’s too controlled, too curated, too conceptual. “People have chosen to abandon the random elements,” he says. If you look at your Instagram feed, you’ll see he’s right. Though photos on ephemeral platforms like Snapchat are less carefully constructed, the Internet’s permanent record is full of poses and setups.

This got me thinking about my photographic legacy. I post about a half-dozen pics a week—mostly on Instagram, mostly staged. When I’m gone, my survivors will only know the artful shots of motorcycles, fourth-take selfies with my wife, scenic vistas, and the #dogsofwired.

Read the entire story here.

Image courtesy of Google Search.