[tube]ZlfIVEy_YOA[/tube]

Gravity, the movie, made some “waves” at the recent Academy Awards ceremony in Hollywood. But the real star in this case, is the real gravity that seems to hold all macroscopic things in the cosmos together. And the waves in the this case are real gravitational waves. A long-running experiment based at the South Pole has discerned a signal from the Cosmic Microwave Background that points to the existence of gravitational waves. This is a discovery of great significance, if upheld, and confirms the Inflationary Theory of our universe’s exponential expansion just after the Big Bang. Theorists who first proposed this remarkable hypothesis — Alan Guth (1979) and Andrei Linde (1981) — are probably popping some champagne right now.

From the New Statesman:

The announcement yesterday that scientists working on the BICEP2 experiment in Antarctica had detected evidence of “inflation” may not appear incredible, but it is. It appears to confirm longstanding hypotheses about the Big Bang and the earliest moments of our universe, and could open a new path to resolving some of physics’ most difficult mysteries.

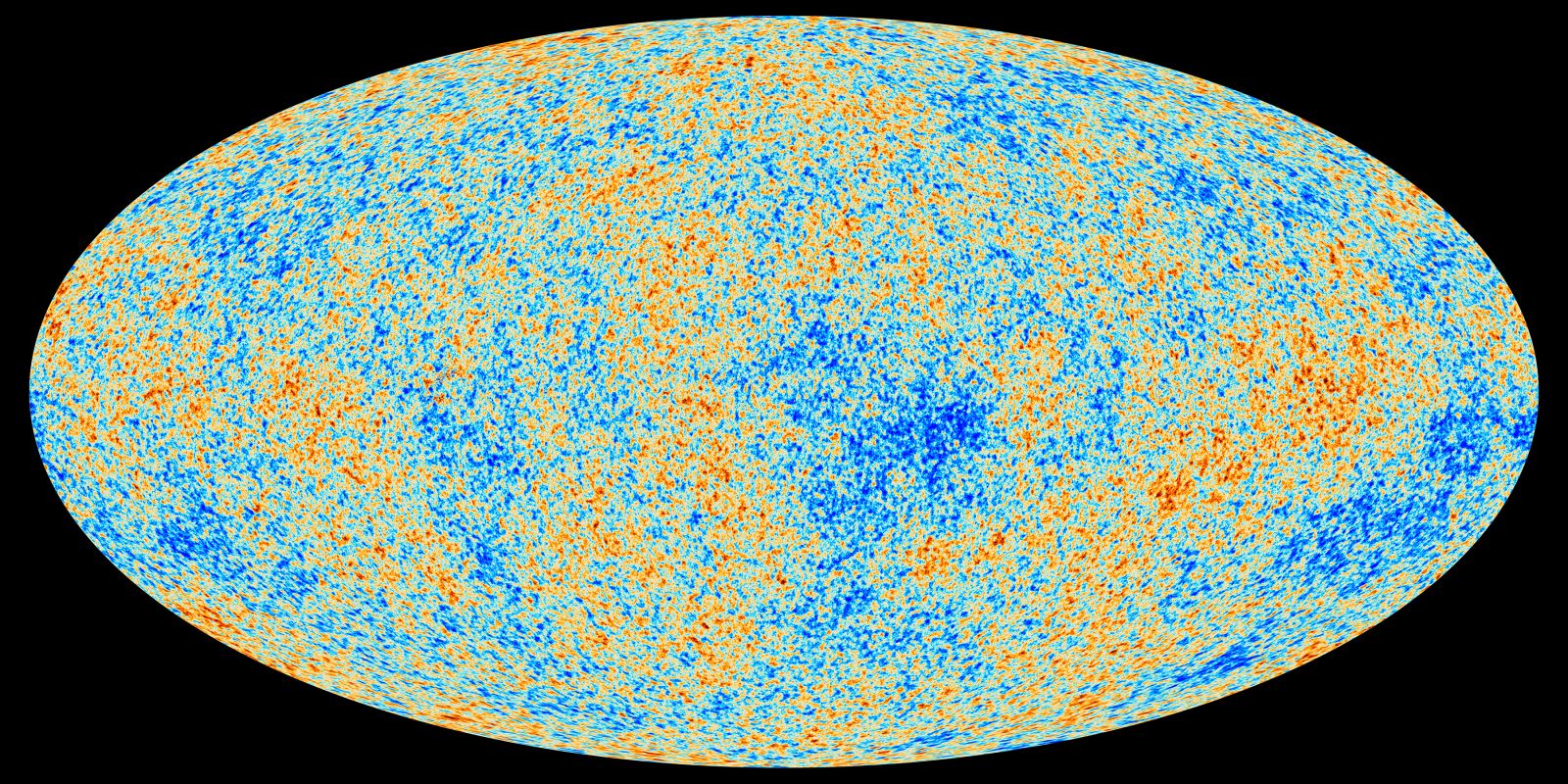

Here’s the explainer. BICEP2, near the South Pole (where the sky is clearest of pollution), was scanning the visible universe for cosmic background radiation – that is, the fuzzy warmth left over from the Big Bang. It’s the oldest light in the universe, and as such our maps of it are our oldest glimpses of the young universe. Here’s a map created with data collected by the ESA’s Planck Surveyor probe last year:

What should be clear from this is that the universe is remarkably flat and regular – that is, there aren’t massive clumps of radiation in some areas and gaps in others. This doesn’t quite make intuitive sense.

If the Big Bang really was a chaotic event, with energy and matter being created and destroyed within tiny fractions of nanoseconds, then we would expect the net result to be a universe that’s similarly chaotic in its structure. Something happened to smooth everything out, and that something is inflation.

Inflation assumes that something must have happened to the rate of expansion of the universe, somewhere between 10-35 and 10-32 seconds after the Big Bang, to make it massively increase. It would mean that the size of the “lumps” would outpace the rate at which they appear in the cosmos, smoothing them out.

For an analogy, imagine if the Moon was suddenly stretched out to the size of the Sun. You’d see – just before it collapsed in on itself – that its rifts and craters had become, relative to its new size, made barely perceptible. Just like a sheet being pulled tightly on a bed, a chaotic structure becomes more uniform.

Inflation, first theorised by Alan Guth in 1979 and refined by Andrei Linde in 1981, became the best hypothesis to explain what we were observing in the universe. It also seemed to offer a way to better understand how dark energy drove the expansion of the Big Bang, and even possibly lead a way towards unifying quantum mechanics with general relativity. That is, if it was correct. And there have been plenty of theories which tied-up some loose ends only to come apart with further observation.

The key evidence needed to verify inflation would be in the form of gravitational waves – that is, ripples in spacetime. Such waves were a part of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and in the 90s scientists observed some for the first time, but until now there’s never been any evidence of them from inside the cosmic background radiation.

BICEP2, though, has found that evidence, and with it scientists now have a crucial piece of fact that can falsify other theories about the early universe and potentially open up entirely new areas of investigation. This is why it’s being compared with the discovery of the Higgs Boson last year, as just as that particle was fundamental to our understanding of molecular physics, so to is inflation to our understanding of the wider universe.

Read the entire article here.

Video: Professor physicist Chao-Lin Kuo delivers news of results from his gravitational wave experiment. Professor Andrei Linde reacts to the discovery, March 17, 2014. Courtesy of Stanford University.

Davide Castelvecchi over at Degrees of Freedom visits with one of the founding fathers of modern cosmology, Alan Guth.

Davide Castelvecchi over at Degrees of Freedom visits with one of the founding fathers of modern cosmology, Alan Guth.