Do you prefer the Beatles to Beethoven? Do you prefer Rembrandt over the Sunday comics or the latest Marvel? Do you read Patterson or Proust? Gary Gutting professor of philosophy argues that the distinguishing value of aesthetics must drive us to appreciate fine art over popular work. So, you had better dust off those volumes of Shakespeare.

Do you prefer the Beatles to Beethoven? Do you prefer Rembrandt over the Sunday comics or the latest Marvel? Do you read Patterson or Proust? Gary Gutting professor of philosophy argues that the distinguishing value of aesthetics must drive us to appreciate fine art over popular work. So, you had better dust off those volumes of Shakespeare.

From the New York Times:

Our democratic society is uneasy with the idea that traditional “high culture” (symphonies, Shakespeare, Picasso) is superior to popular culture (rap music, TV dramas, Norman Rockwell). Our media often make a point of blurring the distinction: newspapers and magazines review rock concerts alongside the Met’s operas and “Batman” sequels next to Chekhov plays. Sophisticated academic critics apply the same methods of analysis and appreciation to Proust and to comic books. And at all levels, claims of objective artistic superiority are likely to be met with smug assertions that all such claims are merely relative to subjective individual preferences.

Our democratic unease is understandable, since the alleged superiority of high culture has often supported the pretensions of an aristocratic class claiming to have privileged access to it. For example, Virginia Woolf’s classic essay — arch, snobbish, and very funny — reserved the appreciation of great art to “highbrows”: those “thoroughbreds of the mind” who combine innate taste with sufficient inherited wealth to sustain a life entirely dedicated to art. Lowbrows were working-class people who had neither the taste nor the time for the artistic life. Woolf claimed to admire lowbrows, who did the work highbrows like herself could not and accepted their cultural inferiority. But she expresses only disdain for a third class — the “middlebrows”— who have earned (probably through trade) enough money to purchase the marks of a high culture that they could never properly appreciate. Middlebrows pursue “no single object, neither art itself nor life itself, but both mixed indistinguishably, and rather nastily, with money, fame, power, or prestige.”

There is, however, no need to tie a defense of high art to Woolf’s “snobocracy.” We can define the high/popular distinction directly in terms of aesthetic quality, without tendentious connections to social status or wealth. Moreover, we can appropriate Woolf’s term “middlebrow,” using it to refer to those, not “to the manner born,” who, admirably, employ the opportunities of a democratic society to reach a level of culture they were not born into.

At this point, however, we can no longer avoid the hovering relativist objection: How do we know that there are any objective criteria that authorize claims that one kind of art is better than another?

Centuries of unresolved philosophical debate show that there is, in fact, little hope of refuting someone who insists on a thoroughly relativist view of art. We should not expect, for example, to provide a definition of beauty (or some other criterion of artistic excellence) that we can use to prove to all doubters that, say, Mozart’s 40th Symphony is objectively superior as art to “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” But in practice there is no need for such a proof, since hardly anyone really holds the relativist view. We may say, “You can’t argue about taste,” but when it comes to art we care about, we almost always do.

For example, fans of popular music may respond to the elitist claims of classical music with a facile relativism. But they abandon this relativism when arguing, say, the comparative merits of the early Beatles and the Rolling Stones. You may, for example, maintain that the Stones were superior to the Beatles (or vice versa) because their music is more complex, less derivative, and has greater emotional range and deeper intellectual content. Here you are putting forward objective standards from which you argue for a band’s superiority. Arguing from such criteria implicitly rejects the view that artistic evaluations are simply matters of personal taste. You are giving reasons for your view that you think others ought to accept.

Further, given the standards fans use to show that their favorites are superior, we can typically show by those same standards that works of high art are overall superior to works of popular art. If the Beatles are better than the Stones in complexity, originality, emotional impact, and intellectual content, then Mozart’s operas are, by those standards, superior to the Beatles’ songs. Similarly, a case for the superiority of one blockbuster movie over another would most likely invoke standards of dramatic power, penetration into character, and quality of dialogue by which almost all blockbuster movies would pale in comparison to Sophocles or Shakespeare.

On reflection, it’s not hard to see why — keeping to the example of music —classical works are in general capable of much higher levels of aesthetic value than popular ones. Compared to a classical composer, someone writing a popular song can utilize only a very small range of musical possibilities: a shorter time span, fewer kinds of instruments, a lower level of virtuosity and a greatly restricted range of compositional techniques. Correspondingly, classical performers are able to supply whatever the composers need for a given piece; popular performers seriously restrict what composers can ask for. Of course, there are sublime works that make minimal performance demands. But constant restriction of resources reduces the opportunities for greater achievement.

Read the entire article here.

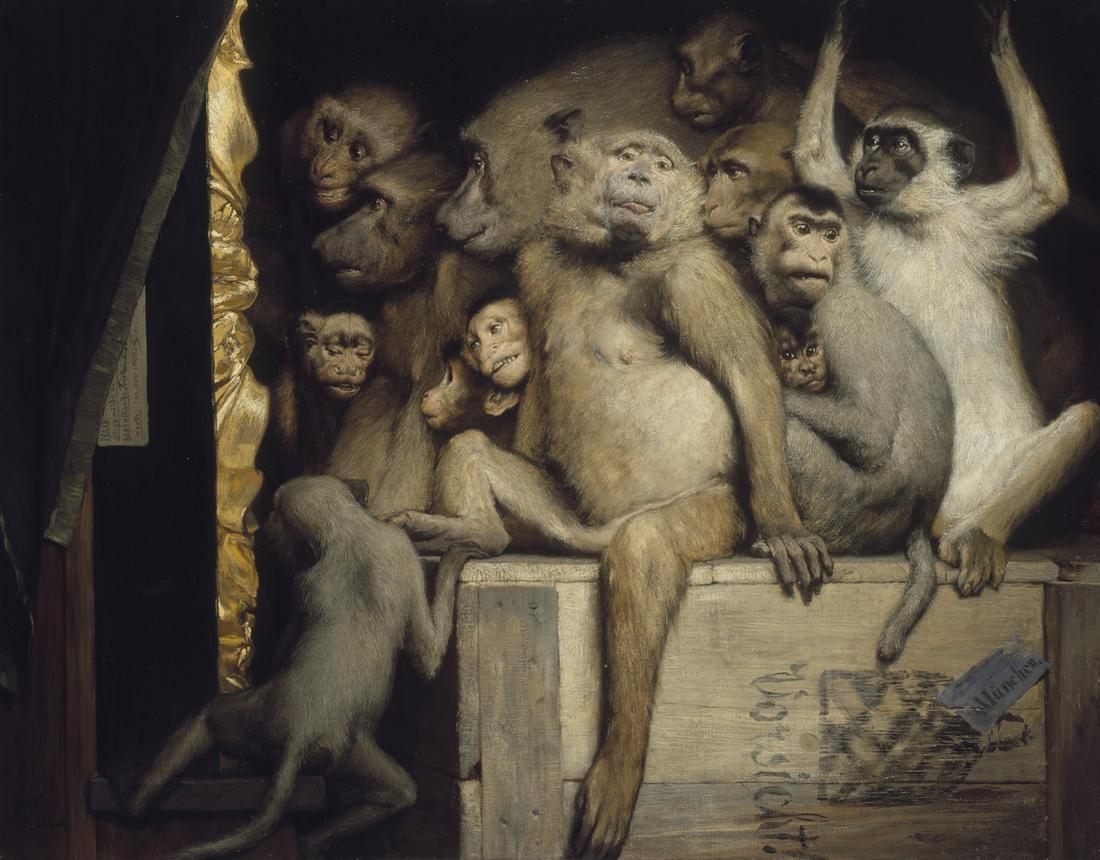

Image: Detail of the face of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Cropped version of the painting where Mozart is seen with Anna Maria (Mozart’s sister) and father, Leopold, on the wall a portrait of his deceased mother, Anna Maria. By Johann Nepomuk della Croce (1736-1819). Courtesy of Wikipedia.

[div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div] Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

The lengthy corridors of art history over the last five hundred years are decorated with numerous bold and monumental works. Just to name a handful of memorable favorites you’ll see a pattern emerge:

The lengthy corridors of art history over the last five hundred years are decorated with numerous bold and monumental works. Just to name a handful of memorable favorites you’ll see a pattern emerge: