It’s a simple equation: too many humans, not enough work. Low paying, physical jobs continue to disappear, replaced by mechanization. More cognitive work characterized by the need to think is increasingly likely to be automated and robotized. This has complex and dire consequences, and not just global economic ramifications, but moral ones. What are we to make of ourselves and of a culture that has intimately linked work with meaning when the work is outsourced or eliminated entirely?

A striking example comes from the richest country in the world — the United States. Recently and anomalously life-expectancy has shown a decrease among white people in economically depressed areas of the nation. Many economists suggest that the quest for ever-increasing productivity — usually delivered through automation — is chipping away at the very essence of what it means to be human: value purpose through work.

James Livingston professor of history at Rutgers University summarizes the existential dilemma, excerpted below, in his latest book No More Work: Why Full Employment is a Bad Idea.

From aeon:

Work means everything to us Americans. For centuries – since, say, 1650 – we’ve believed that it builds character (punctuality, initiative, honesty, self-discipline, and so forth). We’ve also believed that the market in labour, where we go to find work, has been relatively efficient in allocating opportunities and incomes. And we’ve believed that, even if it sucks, a job gives meaning, purpose and structure to our everyday lives – at any rate, we’re pretty sure that it gets us out of bed, pays the bills, makes us feel responsible, and keeps us away from daytime TV.

These beliefs are no longer plausible. In fact, they’ve become ridiculous, because there’s not enough work to go around, and what there is of it won’t pay the bills – unless of course you’ve landed a job as a drug dealer or a Wall Street banker, becoming a gangster either way.

These days, everybody from Left to Right – from the economist Dean Baker to the social scientist Arthur C Brooks, from Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump – addresses this breakdown of the labour market by advocating ‘full employment’, as if having a job is self-evidently a good thing, no matter how dangerous, demanding or demeaning it is. But ‘full employment’ is not the way to restore our faith in hard work, or in playing by the rules, or in whatever else sounds good. The official unemployment rate in the United States is already below 6 per cent, which is pretty close to what economists used to call ‘full employment’, but income inequality hasn’t changed a bit. Shitty jobs for everyone won’t solve any social problems we now face.

Don’t take my word for it, look at the numbers. Already a fourth of the adults actually employed in the US are paid wages lower than would lift them above the official poverty line – and so a fifth of American children live in poverty. Almost half of employed adults in this country are eligible for food stamps (most of those who are eligible don’t apply). The market in labour has broken down, along with most others.

Those jobs that disappeared in the Great Recession just aren’t coming back, regardless of what the unemployment rate tells you – the net gain in jobs since 2000 still stands at zero – and if they do return from the dead, they’ll be zombies, those contingent, part-time or minimum-wage jobs where the bosses shuffle your shift from week to week: welcome to Wal-Mart, where food stamps are a benefit.

Read the entire essay here.

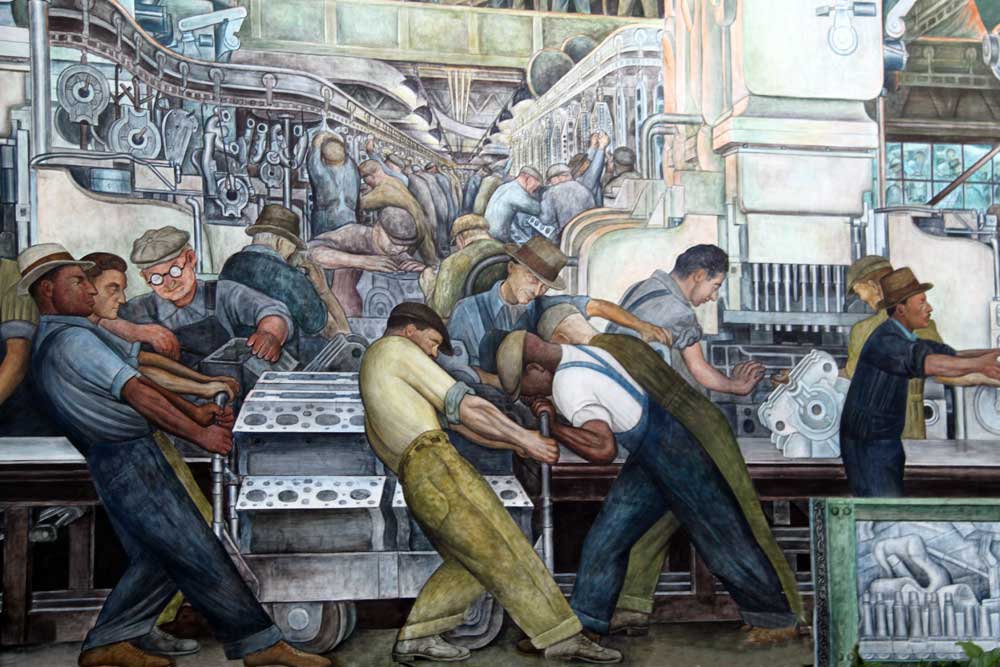

Image: Detroit Industry North Wall, Diego Rivera. Courtesy: Detroit Institute of Arts. Wikipedia.

Leaving the merits of capitalism or socialism aside for a moment, let’s consider the case for taxing bad behavior versus good. Adam Davidson, economics columnist and founder of NPR’s Planet Money, reviews the case now being made by a growing number of economists on both the left and the right. They all come to a similar conclusion: Forget about taxing good or constrictive behavior such as entrepreneurialism. Rather, it’s time to tax people for doing destructive and damaging things.

Leaving the merits of capitalism or socialism aside for a moment, let’s consider the case for taxing bad behavior versus good. Adam Davidson, economics columnist and founder of NPR’s Planet Money, reviews the case now being made by a growing number of economists on both the left and the right. They all come to a similar conclusion: Forget about taxing good or constrictive behavior such as entrepreneurialism. Rather, it’s time to tax people for doing destructive and damaging things.