[div class=attrib]The Globe and Mail:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]The Globe and Mail:[end-div]

The iconic writer reveals the shape of things to come, with 45 tips for survival and a matching glossary of the new words you’ll need to talk about your messed-up future.

1) It’s going to get worse

No silver linings and no lemonade. The elevator only goes down. The bright note is that the elevator will, at some point, stop.

2) The future isn’t going to feel futuristic

It’s simply going to feel weird and out-of-control-ish, the way it does now, because too many things are changing too quickly. The reason the future feels odd is because of its unpredictability. If the future didn’t feel weirdly unexpected, then something would be wrong.

3) The future is going to happen no matter what we do. The future will feel even faster than it does now

The next sets of triumphing technologies are going to happen, no matter who invents them or where or how. Not that technology alone dictates the future, but in the end it always leaves its mark. The only unknown factor is the pace at which new technologies will appear. This technological determinism, with its sense of constantly awaiting a new era-changing technology every day, is one of the hallmarks of the next decade.

4)Move to Vancouver, San Diego, Shannon or Liverpool

There’ll be just as much freaky extreme weather in these west-coast cities, but at least the west coasts won’t be broiling hot and cryogenically cold.

5) You’ll spend a lot of your time feeling like a dog leashed to a pole outside the grocery store – separation anxiety will become your permanent state

6) The middle class is over. It’s not coming back

Remember travel agents? Remember how they just kind of vanished one day?

That’s where all the other jobs that once made us middle-class are going – to that same, magical, class-killing, job-sucking wormhole into which travel-agency jobs vanished, never to return. However, this won’t stop people from self-identifying as middle-class, and as the years pass we’ll be entering a replay of the antebellum South, when people defined themselves by the social status of their ancestors three generations back. Enjoy the new monoclass!

7) Retail will start to resemble Mexican drugstores

In Mexico, if one wishes to buy a toothbrush, one goes to a drugstore where one of every item for sale is on display inside a glass display case that circles the store. One selects the toothbrush and one of an obvious surplus of staff runs to the back to fetch the toothbrush. It’s not very efficient, but it does offer otherwise unemployed people something to do during the day.

8) Try to live near a subway entrance

In a world of crazy-expensive oil, it’s the only real estate that will hold its value, if not increase.

9) The suburbs are doomed, especially thoseE.T. , California-style suburbs

This is a no-brainer, but the former homes will make amazing hangouts for gangs, weirdoes and people performing illegal activities. The pretend gates at the entranceways to gated communities will become real, and the charred stubs of previous white-collar homes will serve only to make the still-standing structures creepier and more exotic.

10) In the same way you can never go backward to a slower computer, you can never go backward to a lessened state of connectedness

11) Old people won’t be quite so clueless

No more “the Google,” because they’ll be just that little bit younger.

12) Expect less

Not zero, just less.

13) Enjoy lettuce while you still can

And anything else that arrives in your life from a truck, for that matter. For vegetables, get used to whatever it is they served in railway hotels in the 1890s. Jams. Preserves. Pickled everything.

14) Something smarter than us is going to emerge

Thank you, algorithms and cloud computing.

15) Make sure you’ve got someone to change your diaper

Sponsor a Class of 2112 med student. Adopt up a storm around the age of 50.

16) “You” will be turning into a cloud of data that circles the planet like a thin gauze

While it’s already hard enough to tell how others perceive us physically, your global, phantom, information-self will prove equally vexing to you: your shopping trends, blog residues, CCTV appearances – it all works in tandem to create a virtual being that you may neither like nor recognize.

17) You may well burn out on the effort of being an individual

You’ve become a notch in the Internet’s belt. Don’t try to delude yourself that you’re a romantic lone individual. To the new order, you’re just a node. There is no escape

18) Untombed landfills will glut the market with 20th-century artifacts

19) The Arctic will become like Antarctica – an everyone/no one space

Who owns Antarctica? Everyone and no one. It’s pie-sliced into unenforceable wedges. And before getting huffy, ask yourself, if you’re a Canadian: Could you draw an even remotely convincing map of all those islands in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories? Quick, draw Ellesmere Island.

20)

North America can easily fragment quickly as did the Eastern Bloc in 1989

Quebec will decide to quietly and quite pleasantly leave Canada. California contemplates splitting into two states, fiscal and non-fiscal. Cuba becomes a Club Med with weapons. The Hate States will form a coalition.

21) We will still be annoyed by people who pun, but we will be able to show them mercy because punning will be revealed to be some sort of connectopathic glitch: The punner, like someone with Tourette’s, has no medical ability not to pun

22) Your sense of time will continue to shred. Years will feel like hours

23) Everyone will be feeling the same way as you

There’s some comfort to be found there.

24) It is going to become much easier to explain why you are the way you are

Much of what we now consider “personality” will be explained away as structural and chemical functions of the brain.

25) Dreams will get better

26)

Being alone will become easier

27)Hooking up will become ever more mechanical and binary

28) It will become harder to view your life as “a story”

The way we define our sense of self will continue to morph via new ways of socializing. The notion of your life needing to be a story will seem slightly corny and dated. Your life becomes however many friends you have online.

29) You will have more say in how long or short you wish your life to feel

Time perception is very much about how you sequence your activities, how many activities you layer overtop of others, and the types of gaps, if any, you leave in between activities.

30) Some existing medical conditions will be seen as sequencing malfunctions

The ability to create and remember sequences is an almost entirely human ability (some crows have been shown to sequence). Dogs, while highly intelligent, still cannot form sequences; it’s the reason why well-trained dogs at shows are still led from station to station by handlers instead of completing the course themselves.

Dysfunctional mental states stem from malfunctions in the brain’s sequencing capacity. One commonly known short-term sequencing dysfunction is dyslexia. People unable to sequence over a slightly longer term might be “not good with directions.” The ultimate sequencing dysfunction is the inability to look at one’s life as a meaningful sequence or story.

31) The built world will continue looking more and more like Microsoft packaging

“We were flying over Phoenix, and it looked like the crumpled-up packaging from a 2006 MS Digital Image Suite.”

32) Musical appreciation will shed all age barriers

33) People who shun new technologies will be viewed as passive-aggressive control freaks trying to rope people into their world, much like vegetarian teenage girls in the early 1980s

1980: “We can’t go to that restaurant. Karen’s vegetarian and it doesn’t have anything for her.”

2010: “What restaurant are we going to? I don’t know. Karen was supposed to tell me, but she doesn’t have a cell, so I can’t ask her. I’m sick of her crazy control-freak behaviour. Let’s go someplace else and not tell her where.”

34) You’re going to miss the 1990s more than you ever thought

35) Stupid people will be in charge, only to be replaced by ever-stupider people. You will live in a world without kings, only princes in whom our faith is shattered

36) Metaphor drift will become pandemic

Words adopted by technology will increasingly drift into new realms to the point where they observe different grammatical laws, e.g., “one mouse”/“three mouses;” “memory hog”/“delete the spam.”

37) People will stop caring how they appear to others

The number of tribal categories one can belong to will become infinite. To use a high-school analogy, 40 years ago you had jocks and nerds. Nowadays, there are Goths, emos, punks, metal-heads, geeks and so forth.

38)Knowing everything will become dull

It all started out so graciously: At a dinner for six, a question arises about, say, that Japanese movie you saw in 1997 (Tampopo), or whether or not Joey Bishop is still alive (no). And before long, you know the answer to everything.

39) IKEA will become an ever-more-spiritual sanctuary

40) We will become more matter-of-fact, in general, about our bodies

41) The future of politics is the careful and effective implanting into the minds of voters images that can never be removed

42) You’ll spend a lot of time shopping online from your jail cell

Over-criminalization of the populace, paired with the triumph of shopping as a dominant cultural activity, will create a world where the two poles of society are shopping and jail.

43) Getting to work will provide vibrant and fun new challenges

Gravel roads, potholes, outhouses, overcrowded buses, short-term hired bodyguards, highwaymen, kidnapping, overnight camping in fields, snaggle-toothed crazy ladies casting spells on you, frightened villagers, organ thieves, exhibitionists and lots of healthy fresh air.

44) Your dream life will increasingly look like Google Street View

45) We will accept the obvious truth that we brought this upon ourselves

Douglas Coupland is a writer and artist based in Vancouver, where he will deliver the first of five CBC Massey Lectures – a ‘novel in five hours’ about the future – on Tuesday.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

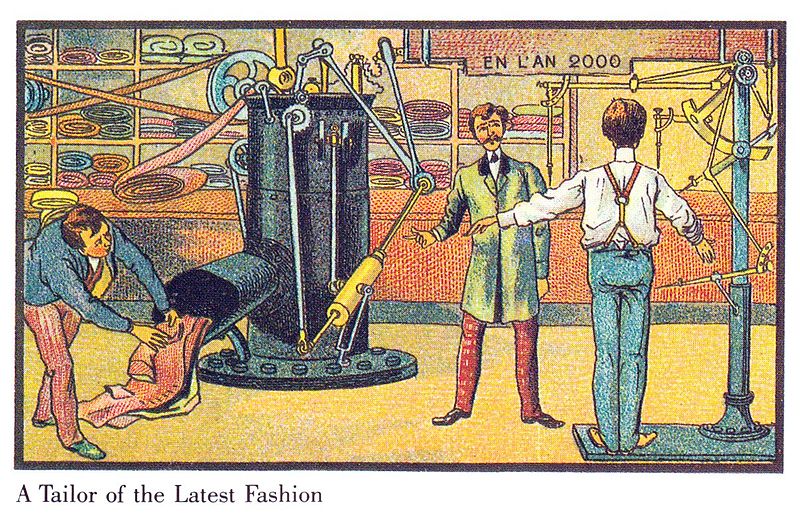

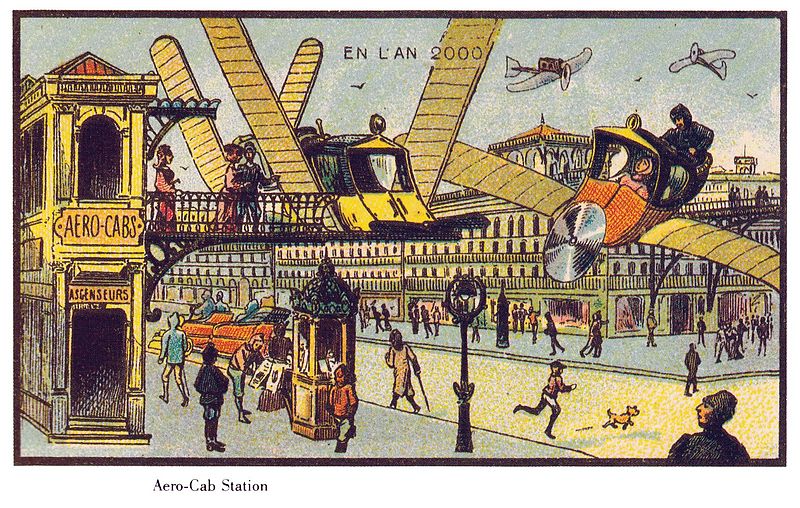

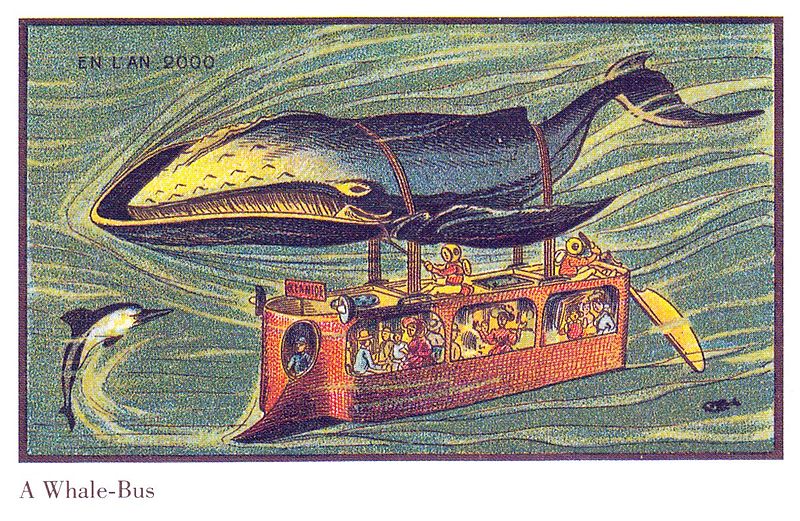

Just over a hundred years ago, at the turn of the 19th century, Jean-Marc Côté and some of his fellow French artists were commissioned to imagine what the world would look like in 2000. Their colorful sketches and paintings portrayed some interesting inventions, though all seem to be grounded in familiar principles and incremental innovations — mechanical helpers, ubiquitous propellers and wings. Interestingly, none of these artist-futurists imagined a world beyond Victorian dress, gender inequality and wars. But these are gems nonetheless.

Just over a hundred years ago, at the turn of the 19th century, Jean-Marc Côté and some of his fellow French artists were commissioned to imagine what the world would look like in 2000. Their colorful sketches and paintings portrayed some interesting inventions, though all seem to be grounded in familiar principles and incremental innovations — mechanical helpers, ubiquitous propellers and wings. Interestingly, none of these artist-futurists imagined a world beyond Victorian dress, gender inequality and wars. But these are gems nonetheless. Some of their works found their way into cigar boxes and cigarette cases, others were exhibited at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris. My three favorites: a Tailor of the Latest Fashion, the Aero-cab Station and the Whale Bus. See the full complement of these remarkable futuristic visions at the Public Domain Review, and check out the House Rolling Through the Countryside and At School.

Some of their works found their way into cigar boxes and cigarette cases, others were exhibited at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris. My three favorites: a Tailor of the Latest Fashion, the Aero-cab Station and the Whale Bus. See the full complement of these remarkable futuristic visions at the Public Domain Review, and check out the House Rolling Through the Countryside and At School. Images courtesy of the Public Domain Review, a project of the Open Knowledge Foundation. Public Domain.

Images courtesy of the Public Domain Review, a project of the Open Knowledge Foundation. Public Domain.

By all accounts serial entrepreneur, inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil is Google’s most famous employee, eclipsing even co-founders Larry Page and Sergei Brin. As an inventor he can lay claim to some impressive firsts, such as the flatbed scanner, optical character recognition and the music synthesizer. As a futurist, for which he is now more recognized in the public consciousness, he ponders longevity, immortality and the human brain.

By all accounts serial entrepreneur, inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil is Google’s most famous employee, eclipsing even co-founders Larry Page and Sergei Brin. As an inventor he can lay claim to some impressive firsts, such as the flatbed scanner, optical character recognition and the music synthesizer. As a futurist, for which he is now more recognized in the public consciousness, he ponders longevity, immortality and the human brain. [div class=attrib]The Globe and Mail:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]The Globe and Mail:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div]