A small proportion of classic movies remain in circulation and in our memories. Most are quickly forgotten. And some simply go missing. How could an old movie go missing? Well, it’s not very difficult: a temperamental, perfectionist director may demand the original be buried; or a fickle movie studio may wish to hide and remove all traces of last season’s flop; or some old reels, cast in nitrates, may just burn, literally. But, every once in a while an old movie is found in a dusty attic or damp basement. Or as is the case of a more recent find — film reels in a dumpster (if you’re a Brit, that’s a “skip”). Two recent discoveries shed more light on the developing comedic talent of Peter Sellers.

From the Guardian:

In the mid-1950s, Peter Sellers was young and ambitious and still largely unseen. He wanted to break out of his radio ghetto and achieve big-screen success, so he played a bumbling crook in The Ladykillers and a bumbling everyman in a series of comedy shorts for an independent production company called Park Lane Films. The Ladykillers endured and is cherished to this day. The shorts came and then went and were quickly forgotten. To all intents and purposes, they never existed at all.

I’m fascinated by the idea of the films that get lost; that vast, teeming netherworld where the obscure and the unloved rub shoulders, in the dark, with the misplaced and the mythic. Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation estimates that as many as 50% of the American movies made before 1950 are now gone for good, while the British film archive is similarly holed like Swiss cheese. Somewhere out there, languishing in limbo, are missing pictures from directors including Orson Welles, Michael Powell and Alfred Hitchcock. Most of these orphans will surely never be found. Yet sometimes, against the odds, one will abruptly surface.

In his duties as facilities manager at an office block in central London, Robert Farrow would occasionally visit the basement area where the janitors parked their mops, brooms and vacuum cleaners. Nestled amid this equipment was a stack of 21 canisters, which Farrow assumed contained polishing pads for the cleaning machines. Years later, during an office refurbishment, Farrow saw that these canisters had been removed from the basement and dumped outside in a skip. “You don’t expect to find anything valuable in a skip,” Farrow says ruefully. But inside the canisters he found the lost Sellers shorts.

It’s a blustery spring day when we gather at a converted water works in Southend-on-Sea to meet the movie orphans. Happily the comedies – Dearth of a Salesman and Insomnia is Good For You – have been brushed up in readiness. They have been treated to a spick-and-span Telecine scan and look none the worse for their years in the basement. Each will now premiere (or perhaps re-premiere) at the Southend film festival, nestled amid the screenings of The Great Beauty and Wadjda and a retrospective showing of Sellers’ 1969 fantasy The Magic Christian. In the meantime, festival director Paul Cotgrove has hailed their reappearance as the equivalent of “finding the Dead Sea Scrolls”.

I think that might be overselling it, although one can understand his excitement. Instead, the films might best be viewed as crucial stepping stones, charting a bright spark’s evolution into a fully fledged film star. At the time they were made, Sellers was a big fish in a small pond, flushed from the success of The Goon Show and half-wondering whether he had already peaked. “By this point he had hardly done anything on screen,” Cotgrove explains. “He was obsessed with breaking away from radio and getting into film. You can see the early styles in these films that he would then use later on.”

To the untrained eye, he looks to be adapting rather well. Dearth of a Salesman and Insomnia is Good For You both run 29 minutes and come framed as spoof information broadcasts, installing Sellers in the role of lowly Herbert Dimwitty. In the first, Dimwitty attempts to strike out as a go-getting entrepreneur, peddling print dresses and dishwashers and regaling his clients with a range of funny accents. “I’m known as the Peter Ustinov of East Acton,” he informs a harried suburban housewife.

Dearth, it must be said, feels a little faded and cosy; its line in comedy too thinly spread. But Insomnia is terrific. Full of spark, bite and invention, the film chivvies Sellers’s sleep-deprived employee through a “good night’s wake”, thrilling to the “tone poem” of nocturnal noises from the street outside and replaying awkward moments from the office until they bloom into full-on waking nightmares. Who cares if Dimwitty is little more than a low-rent archetype, the kind of bumbling sitcom staple that has been embodied by everyone from Tony Hancock to Terry Scott? Sellers keeps the man supple and spiky. It’s a role the actor would later reprise, with a few variations, in the 1962 Kingsley Amis adaptation Only Two Can Play.

But what were these pictures and where did they go? Cotgrove and Farrow’s research can only take us so far. Dearth and Insomnia were probably shot in 1956, or possibly 1957, for Park Lane Films, which then later went bust. They would have played in British cinemas ahead of the feature presentation, folded in among the cartoons and the news, and may even have screened in the US and Canada as well. Records suggest that Sellers was initially contracted to shoot 12 movies in total, but may well have wriggled out of the deal after The Ladykillers was released. Only three have been found: Dearth, Insomnia and the below-par Cold Comfort, which was already in circulation. Conceivably there might be more Sellers shorts out there somewhere, either idling in skips or buried in basements. But there is no way of knowing; it’s akin to proving a negative. Cotgrove and Farrow aren’t even sure who owns the copyright. “If you find something on the street, it’s not yours,” Farrow points out. “You only have guardianship.”

As it is, the Sellers shorts can be safely filed away among other reclaimed items, plucked out of a skip and brought in from the cold. They take their place alongside such works as Carl Dreyer’s silent-screen classic The Passion of Joan of Arc, which turned up (unaccountably) at a Norwegian psychiatric hospital, or the vital lost footage from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, found in Buenos Aires back in 2008. But these happy few are just the tip of the iceberg. Thousands of movies have simply vanished from view.

Read the entire article here.

Image: Still from newly discovered movie Dearth of a Salesman, featuring a young Peter Sellers. Courtesy of Southend Film Festival / Guardian.

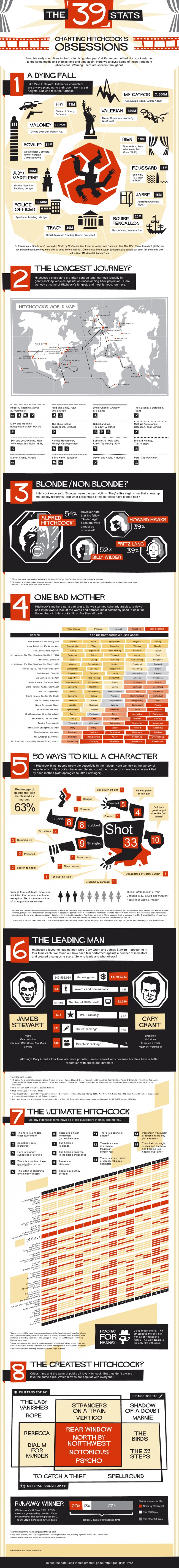

Alfred Hitchcock was a pioneer of modern cinema. His finely crafted movies introduced audiences to new levels of suspense, sexuality and violence. His work raised cinema to the level of great art.

Alfred Hitchcock was a pioneer of modern cinema. His finely crafted movies introduced audiences to new levels of suspense, sexuality and violence. His work raised cinema to the level of great art.