You could argue that technology has altered how we learn, and you would be partly correct. You could also argue that our children are also much more informed and learned compared with their peers in Victorian England, and, again, you would be partly correct. But the most critical element remains the same — the process. The regimented approach, the rote teaching, the focus on tests and testing, and the systematic squelching of creativity still remains solidly in place.

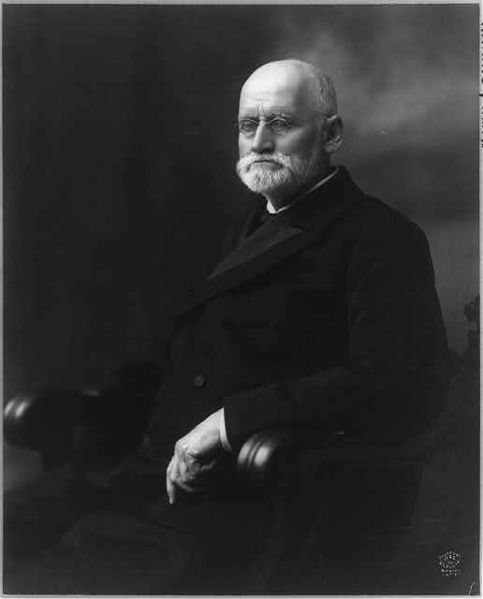

William Torrey Harris, one of the founders of the U.S. public school system in the late-1800s, once said,

And, in testament to his enduring legacy, much of this can still be seen in action today in most Western public schools.

José Urbina López Primary School sits next to a dump just across the US border in Mexico. The school serves residents of Matamoros, a dusty, sunbaked city of 489,000 that is a flash point in the war on drugs. There are regular shoot-outs, and it’s not uncommon for locals to find bodies scattered in the street in the morning. To get to the school, students walk along a white dirt road that parallels a fetid canal. On a recent morning there was a 1940s-era tractor, a decaying boat in a ditch, and a herd of goats nibbling gray strands of grass. A cinder-block barrier separates the school from a wasteland—the far end of which is a mound of trash that grew so big, it was finally closed down. On most days, a rotten smell drifts through the cement-walled classrooms. Some people here call the school un lugar de castigo—”a place of punishment.”

For 12-year-old Paloma Noyola Bueno, it was a bright spot. More than 25 years ago, her family moved to the border from central Mexico in search of a better life. Instead, they got stuck living beside the dump. Her father spent all day scavenging for scrap, digging for pieces of aluminum, glass, and plastic in the muck. Recently, he had developed nosebleeds, but he didn’t want Paloma to worry. She was his little angel—the youngest of eight children.

After school, Paloma would come home and sit with her father in the main room of their cement-and-wood home. Her father was a weather-beaten, gaunt man who always wore a cowboy hat. Paloma would recite the day’s lessons for him in her crisp uniform—gray polo, blue-and-white skirt—and try to cheer him up. She had long black hair, a high forehead, and a thoughtful, measured way of talking. School had never been challenging for her. She sat in rows with the other students while teachers told the kids what they needed to know. It wasn’t hard to repeat it back, and she got good grades without thinking too much. As she headed into fifth grade, she assumed she was in for more of the same—lectures, memorization, and busy work.

Sergio Juárez Correa was used to teaching that kind of class. For five years, he had stood in front of students and worked his way through the government-mandated curriculum. It was mind-numbingly boring for him and the students, and he’d come to the conclusion that it was a waste of time. Test scores were poor, and even the students who did well weren’t truly engaged. Something had to change.

He too had grown up beside a garbage dump in Matamoros, and he had become a teacher to help kids learn enough to make something more of their lives. So in 2011—when Paloma entered his class—Juárez Correa decided to start experimenting. He began reading books and searching for ideas online. Soon he stumbled on a video describing the work of Sugata Mitra, a professor of educational technology at Newcastle University in the UK. In the late 1990s and throughout the 2000s, Mitra conducted experiments in which he gave children in India access to computers. Without any instruction, they were able to teach themselves a surprising variety of things, from DNA replication to English.

Juárez Correa didn’t know it yet, but he had happened on an emerging educational philosophy, one that applies the logic of the digital age to the classroom. That logic is inexorable: Access to a world of infinite information has changed how we communicate, process information, and think. Decentralized systems have proven to be more productive and agile than rigid, top-down ones. Innovation, creativity, and independent thinking are increasingly crucial to the global economy.

And yet the dominant model of public education is still fundamentally rooted in the industrial revolution that spawned it, when workplaces valued punctuality, regularity, attention, and silence above all else. (In 1899, William T. Harris, the US commissioner of education, celebrated the fact that US schools had developed the “appearance of a machine,” one that teaches the student “to behave in an orderly manner, to stay in his own place, and not get in the way of others.”) We don’t openly profess those values nowadays, but our educational system—which routinely tests kids on their ability to recall information and demonstrate mastery of a narrow set of skills—doubles down on the view that students are material to be processed, programmed, and quality-tested. School administrators prepare curriculum standards and “pacing guides” that tell teachers what to teach each day. Legions of managers supervise everything that happens in the classroom; in 2010 only 50 percent of public school staff members in the US were teachers.

The results speak for themselves: Hundreds of thousands of kids drop out of public high school every year. Of those who do graduate from high school, almost a third are “not prepared academically for first-year college courses,” according to a 2013 report from the testing service ACT. The World Economic Forum ranks the US just 49th out of 148 developed and developing nations in quality of math and science instruction. “The fundamental basis of the system is fatally flawed,” says Linda Darling-Hammond, a professor of education at Stanford and founding director of the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future. “In 1970 the top three skills required by the Fortune 500 were the three Rs: reading, writing, and arithmetic. In 1999 the top three skills in demand were teamwork, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills. We need schools that are developing these skills.”

That’s why a new breed of educators, inspired by everything from the Internet to evolutionary psychology, neuroscience, and AI, are inventing radical new ways for children to learn, grow, and thrive. To them, knowledge isn’t a commodity that’s delivered from teacher to student but something that emerges from the students’ own curiosity-fueled exploration. Teachers provide prompts, not answers, and then they step aside so students can teach themselves and one another. They are creating ways for children to discover their passion—and uncovering a generation of geniuses in the process.

At home in Matamoros, Juárez Correa found himself utterly absorbed by these ideas. And the more he learned, the more excited he became. On August 21, 2011—the start of the school year — he walked into his classroom and pulled the battered wooden desks into small groups. When Paloma and the other students filed in, they looked confused. Juárez Correa invited them to take a seat and then sat down with them.

He started by telling them that there were kids in other parts of the world who could memorize pi to hundreds of decimal points. They could write symphonies and build robots and airplanes. Most people wouldn’t think that the students at José Urbina López could do those kinds of things. Kids just across the border in Brownsville, Texas, had laptops, high-speed Internet, and tutoring, while in Matamoros the students had intermittent electricity, few computers, limited Internet, and sometimes not enough to eat.

“But you do have one thing that makes you the equal of any kid in the world,” Juárez Correa said. “Potential.”

He looked around the room. “And from now on,” he told them, “we’re going to use that potential to make you the best students in the world.”

Paloma was silent, waiting to be told what to do. She didn’t realize that over the next nine months, her experience of school would be rewritten, tapping into an array of educational innovations from around the world and vaulting her and some of her classmates to the top of the math and language rankings in Mexico.

“So,” Juárez Correa said, “what do you want to learn?”

In 1999, Sugata Mitra was chief scientist at a company in New Delhi that trains software developers. His office was on the edge of a slum, and on a hunch one day, he decided to put a computer into a nook in a wall separating his building from the slum. He was curious to see what the kids would do, particularly if he said nothing. He simply powered the computer on and watched from a distance. To his surprise, the children quickly figured out how to use the machine.

Over the years, Mitra got more ambitious. For a study published in 2010, he loaded a computer with molecular biology materials and set it up in Kalikuppam, a village in southern India. He selected a small group of 10- to 14-year-olds and told them there was some interesting stuff on the computer, and might they take a look? Then he applied his new pedagogical method: He said no more and left.

Over the next 75 days, the children worked out how to use the computer and began to learn. When Mitra returned, he administered a written test on molecular biology. The kids answered about one of four questions correctly. After another 75 days, with the encouragement of a friendly local, they were getting every other question right. “If you put a computer in front of children and remove all other adult restrictions, they will self-organize around it,” Mitra says, “like bees around a flower.”

A charismatic and convincing proselytizer, Mitra has become a darling in the tech world. In early 2013 he won a $1 million grant from TED, the global ideas conference, to pursue his work. He’s now in the process of establishing seven “schools in the cloud,” five in India and two in the UK. In India, most of his schools are single-room buildings. There will be no teachers, curriculum, or separation into age groups—just six or so computers and a woman to look after the kids’ safety. His defining principle: “The children are completely in charge.”

Image: William Torrey Harris, (September 10, 1835 – November 5, 1909), American educator, philosopher, and lexicographer. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

[div class=attrib]From the Wall Street Journal:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Wall Street Journal:[end-div]