[div class=attrib]From The New Yorker:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The New Yorker:[end-div]

At four-thirty in the afternoon on Monday, February 1, 1960, four college students sat down at the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. They were freshmen at North Carolina A. & T., a black college a mile or so away.

“I’d like a cup of coffee, please,” one of the four, Ezell Blair, said to the waitress.

“We don’t serve Negroes here,” she replied.

The Woolworth’s lunch counter was a long L-shaped bar that could seat sixty-six people, with a standup snack bar at one end. The seats were for whites. The snack bar was for blacks. Another employee, a black woman who worked at the steam table, approached the students and tried to warn them away. “You’re acting stupid, ignorant!” she said. They didn’t move. Around five-thirty, the front doors to the store were locked. The four still didn’t move. Finally, they left by a side door. Outside, a small crowd had gathered, including a photographer from the Greensboro Record. “I’ll be back tomorrow with A. & T. College,” one of the students said.

By next morning, the protest had grown to twenty-seven men and four women, most from the same dormitory as the original four. The men were dressed in suits and ties. The students had brought their schoolwork, and studied as they sat at the counter. On Wednesday, students from Greensboro’s “Negro” secondary school, Dudley High, joined in, and the number of protesters swelled to eighty. By Thursday, the protesters numbered three hundred, including three white women, from the Greensboro campus of the University of North Carolina. By Saturday, the sit-in had reached six hundred. People spilled out onto the street. White teen-agers waved Confederate flags. Someone threw a firecracker. At noon, the A. & T. football team arrived. “Here comes the wrecking crew,” one of the white students shouted.

By the following Monday, sit-ins had spread to Winston-Salem, twenty-five miles away, and Durham, fifty miles away. The day after that, students at Fayetteville State Teachers College and at Johnson C. Smith College, in Charlotte, joined in, followed on Wednesday by students at St. Augustine’s College and Shaw University, in Raleigh. On Thursday and Friday, the protest crossed state lines, surfacing in Hampton and Portsmouth, Virginia, in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and in Chattanooga, Tennessee. By the end of the month, there were sit-ins throughout the South, as far west as Texas. “I asked every student I met what the first day of the sitdowns had been like on his campus,” the political theorist Michael Walzer wrote in Dissent. “The answer was always the same: ‘It was like a fever. Everyone wanted to go.’ ” Some seventy thousand students eventually took part. Thousands were arrested and untold thousands more radicalized. These events in the early sixties became a civil-rights war that engulfed the South for the rest of the decade—and it happened without e-mail, texting, Facebook, or Twitter.

The world, we are told, is in the midst of a revolution. The new tools of social media have reinvented social activism. With Facebook and Twitter and the like, the traditional relationship between political authority and popular will has been upended, making it easier for the powerless to collaborate, coördinate, and give voice to their concerns. When ten thousand protesters took to the streets in Moldova in the spring of 2009 to protest against their country’s Communist government, the action was dubbed the Twitter Revolution, because of the means by which the demonstrators had been brought together. A few months after that, when student protests rocked Tehran, the State Department took the unusual step of asking Twitter to suspend scheduled maintenance of its Web site, because the Administration didn’t want such a critical organizing tool out of service at the height of the demonstrations. “Without Twitter the people of Iran would not have felt empowered and confident to stand up for freedom and democracy,” Mark Pfeifle, a former national-security adviser, later wrote, calling for Twitter to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Where activists were once defined by their causes, they are now defined by their tools. Facebook warriors go online to push for change. “You are the best hope for us all,” James K. Glassman, a former senior State Department official, told a crowd of cyber activists at a recent conference sponsored by Facebook, A. T. & T., Howcast, MTV, and Google. Sites like Facebook, Glassman said, “give the U.S. a significant competitive advantage over terrorists. Some time ago, I said that Al Qaeda was ‘eating our lunch on the Internet.’ That is no longer the case. Al Qaeda is stuck in Web 1.0. The Internet is now about interactivity and conversation.”

These are strong, and puzzling, claims. Why does it matter who is eating whose lunch on the Internet? Are people who log on to their Facebook page really the best hope for us all? As for Moldova’s so-called Twitter Revolution, Evgeny Morozov, a scholar at Stanford who has been the most persistent of digital evangelism’s critics, points out that Twitter had scant internal significance in Moldova, a country where very few Twitter accounts exist. Nor does it seem to have been a revolution, not least because the protests—as Anne Applebaum suggested in the Washington Post—may well have been a bit of stagecraft cooked up by the government. (In a country paranoid about Romanian revanchism, the protesters flew a Romanian flag over the Parliament building.) In the Iranian case, meanwhile, the people tweeting about the demonstrations were almost all in the West. “It is time to get Twitter’s role in the events in Iran right,” Golnaz Esfandiari wrote, this past summer, in Foreign Policy. “Simply put: There was no Twitter Revolution inside Iran.” The cadre of prominent bloggers, like Andrew Sullivan, who championed the role of social media in Iran, Esfandiari continued, misunderstood the situation. “Western journalists who couldn’t reach—or didn’t bother reaching?—people on the ground in Iran simply scrolled through the English-language tweets post with tag #iranelection,” she wrote. “Through it all, no one seemed to wonder why people trying to coordinate protests in Iran would be writing in any language other than Farsi.”

Some of this grandiosity is to be expected. Innovators tend to be solipsists. They often want to cram every stray fact and experience into their new model. As the historian Robert Darnton has written, “The marvels of communication technology in the present have produced a false consciousness about the past—even a sense that communication has no history, or had nothing of importance to consider before the days of television and the Internet.” But there is something else at work here, in the outsized enthusiasm for social media. Fifty years after one of the most extraordinary episodes of social upheaval in American history, we seem to have forgotten what activism is.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

Perhaps it’s time to re-think your social network when through it you know all about the stranger with whom you are sharing the elevator.

Perhaps it’s time to re-think your social network when through it you know all about the stranger with whom you are sharing the elevator.

In recent years narcissism has been taking a bad rap. So much so that Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) was slated for removal from the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V. The DSM-V is the professional reference guide published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had decided that they needed only 5 fundamental types of personality disorder: anti-social, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal. Hence no need for NPD.

In recent years narcissism has been taking a bad rap. So much so that Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) was slated for removal from the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V. The DSM-V is the professional reference guide published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had decided that they needed only 5 fundamental types of personality disorder: anti-social, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal. Hence no need for NPD. Six degrees of separation is commonly held urban myth that on average everyone on Earth is six connections or less away from any other person. That is, through a chain of friend of a friend (of a friend, etc) relationships you can find yourself linked to the President, the Chinese Premier, a farmer on the steppes of Mongolia, Nelson Mandela, the editor of theDiagonal, and any one of the other 7 billion people on the planet.

Six degrees of separation is commonly held urban myth that on average everyone on Earth is six connections or less away from any other person. That is, through a chain of friend of a friend (of a friend, etc) relationships you can find yourself linked to the President, the Chinese Premier, a farmer on the steppes of Mongolia, Nelson Mandela, the editor of theDiagonal, and any one of the other 7 billion people on the planet. The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes.

The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes. Recollect the piped “musak” that once played, and still plays, in many hotel elevators and public waiting rooms. Remember the perfectly designed mood music in restaurants and museums. Now, re-imagine the ambient soundscape dynamically customized for a space based on the music preferences of the people inhabiting that space. Well, there is a growing list of apps for that.

Recollect the piped “musak” that once played, and still plays, in many hotel elevators and public waiting rooms. Remember the perfectly designed mood music in restaurants and museums. Now, re-imagine the ambient soundscape dynamically customized for a space based on the music preferences of the people inhabiting that space. Well, there is a growing list of apps for that. Counterintuitive results show that we are more likely to resist changing our minds when more people tell us where are wrong. A team of researchers from HP’s Social Computing Research Group found that humans are more likely to change their minds when fewer, rather than more, people disagree with them.

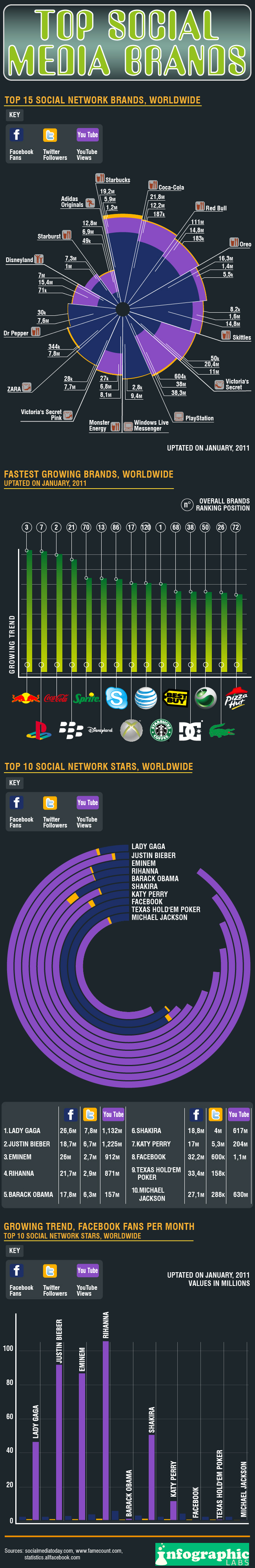

Counterintuitive results show that we are more likely to resist changing our minds when more people tell us where are wrong. A team of researchers from HP’s Social Computing Research Group found that humans are more likely to change their minds when fewer, rather than more, people disagree with them. Accumulating likes, collecting followers and quantifying one’s friends online is serious business. If you don’t have more than a couple of hundred professional connections in your LinkedIn profile or at least twice that number of “friends” through Facebook or ten times that volume of Twittering followers, you’re most likely to be a corporate wallflower, a social has-been.

Accumulating likes, collecting followers and quantifying one’s friends online is serious business. If you don’t have more than a couple of hundred professional connections in your LinkedIn profile or at least twice that number of “friends” through Facebook or ten times that volume of Twittering followers, you’re most likely to be a corporate wallflower, a social has-been.

[div class=attrib]From The New Yorker:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The New Yorker:[end-div] [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]