If you have a child under the age of 13 it’s likely that you’ve heard of, seen or even used Minecraft. More than just a typical online game, Minecraft is a playground for aspiring architects — despite the Creepers. Minecraft began in 2011 with a simple premise — place and remove blocks to fend of unwanted marauders. Now it has become a blank canvas for young minds to design and collaborate on building fantastical structures. My own twin 11 year-olds have designed their dream homes complete with basement stables, glass stairways roof-top pool.

From the Guardian:

I couldn’t pinpoint exactly when I became aware of my eight-year-old son’s fixation with Minecraft. I only know that the odd reference to zombies and pickaxes burgeoned until it was an omnipresent force in our household, the dominant topic of conversation and, most bafflingly, a game he found so gripping that he didn’t just want to play it, he wanted to watch YouTube videos of others playing it too.

This was clearly more than any old computer game – for Otis and, judging by discussion at the school gates, his friends too. I felt as if he’d joined a cult, albeit a reasonably benign one, though as someone who last played a computer game when Jet Set Willy was the height of technological wizardry, I hardly felt in a position to judge.

Minecraft, I realised, was something I knew nothing about. It was time to become acquainted. I announced my intention to give myself a crash course in the game to Otis one evening, interrupting his search for Obsidian to build a portal to the Nether dimension. As you do. “Why would you want to play Minecraft?” he asked, as if I’d confided that I was taking up a career in trapeze-artistry.

For anyone as mystified about it as I was, Minecraft is now one of the world’s biggest computer games, a global phenomenon that’s totted up 14,403,011 purchases as I write; 19,270 in the past 24 hours – live statistics they update on their website, as if it were Children in Need night.

Trying to define the objective of the game isn’t easy. When I ask Otis, he shrugs. “I’m not sure there is one. But that’s what’s brilliant. You can do anything you like.”

This doesn’t seem like much of an insight, though to be fair, the developers themselves, Mojang, define it succinctly as, “a game about breaking and placing blocks”. This sounds delightfully simple, an impression echoed by its graphics. In sharp contrast to the rich, more cinematic style of other games, this is unapologetically old school, the sort of computer game of the future that Marty McFly would have played.

In this case, looks are deceptive. “The pixelated style might appear simple but it masks a huge amount of depth and complexity,” explains Alex Wiltshire, former editor of Edge magazine and author of forthcoming Minecraft guide, Block-o-pedia. “Its complex nature doesn’t lie in detailed art assets, but in how each element of the game interrelates.”

It’s this that gives players the potential to produce elaborate constructions on a lavish scale; fans have made everything from 1:1 scale re-creations of the Lord of the Rings’ Mines of Moria, to models of entire cities.

I’m a long way from that. “Don’t worry, Mum – when I first went on it when I was six, I had no idea what I was doing,” Otis reassures, shaking his head at the thought of those naive days, way back when.

Otis’s device of choice is his iPod, ideal for on-the-move sessions, though this once caused him serious grief after being caught on it under his duvet after lights out. I take one look at the lightning speed with which his fingers move and decide to download it on to my MacBook instead. The introduction of an additional version of the game into our household is greeted very much like Walter Raleigh’s return from the New World.

We open up the game and he tells me that I am “Steve”, the default player, and that we get a choice of modes in which to play: creative or survival. He suggests I start with the former on the basis that this is the best place for those who aren’t very good at it.

In creative mode, you are dropped into a newly generated world (an island in our case) and gifted a raft of resources – everything from coal and lapis lazuli to cake and beds.

At the risk of sounding like a dunce, it isn’t at all obvious what I’m supposed to do. So instead of springing into action, I’m left standing, looking around lamely as if I’m on the edge of a dance floor waiting for someone to come and put me out of my misery. Despite knowing that the major skill required in this game is building, before Otis intervenes, the most I can accomplish is to dig a few holes.

“When it first came out everyone was confused as the developer gave little or no guidance,” says Wiltshire. “It didn’t specifically say you had to cut down a tree to get some wood, whereas games that are produced by big companies give instructions – the last thing they want is for people not to understand how to play. With Minecraft, which had an indie developer, the player had to work things out for themselves. It was quite a tonic.”

He believes that this is why a game not specifically designed for children has become so popular with them. “Because you learn so much when you’re young, kids are used to the idea of a world they don’t fully understand, so they’re comfortable with having to find things out for themselves.”

For the moment, I’m happy to take instruction from my son, who begins his demonstration by creating a rollercoaster – an obvious priority when you’ve just landed on a desert island. He quickly installs its tracks, weaving them through trees and into the sea, before sending Steve for a ride. He asks me if I feel ready to have a go. I feel as if I’m on a nursing home word processing course.

Familiarising yourself takes a little time but once you get going – and have worked out the controls – being able to run, fly, swim and build is undeniably absorbing. I also finally manage to construct something, a slightly disappointing shipping container-type affair that explodes Wiltshire’s assertion that it’s “virtually impossible to build something that looks terrible in Minecraft”. Still, I’m enjoying it, I can’t deny it. Aged eight, I’d have loved it every bit as much as my son does.

The more I play it, the more I also start to understand why this game is been championed for its educational possibilities, with some schools in the US using it as a tool to teach maths and science.

Dr Helen O’Connor, who runs UK-based Childchology – which provides children and their families with support for common psychological problems via the internet – said: “Minecraft offers some strong positives for children. It works on a cognitive level in that it involves problem solving, imagination, memory, creativity and logical sequencing. There is a good educational element to the game, and it also requires some number crunching.

“Unlike lots of other games, there is little violence, with the exception of fighting off a few zombies and creepers. This is perhaps one of the reasons why it is fairly gender neutral and girls enjoy playing it as well as boys.”

The next part of Otis’s demonstration involves switching to survival mode. He explains: “You’ve got to find the resources yourself here. You’re not just given them. Oh and there are villains too. Zombie pigmen and that kind of thing.”

It’s clear that life in survival mode is a significantly hairier prospect than in creative, particularly when Otis changes the difficulty setting to its highest notch. He says he doesn’t do this often because, after spending three weeks creating a house from wood and cobblestones, zombies nearly trashed the place. I make a mental note to remind him of this conversation next time he has a sleepover.

One of the things that’s so appealing about Minecraft is that there is no obvious start and end; it’s a game of infinite possibilities, which is presumably why it’s often compared to Lego. Yet, the addictive nature of the game is clearly vexing many parents: internet talkboards are awash with people seeking advice on how to prize their children away from it.

Read the entire story here.

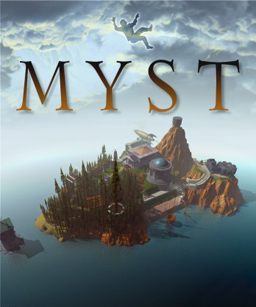

Image courtesy of Minecraft.

Only yesterday we

Only yesterday we