Soon you’ll be able to text and chat online without the need of a cellular network or the Internet. There is a catch though: you’ll need yet another chat-app for your smartphone and you will need to be within a 100 or so yards of your chatting friend. But, this is just the beginning of so-called “mesh networks” that can be formed through peer-to-peer device connections avoiding the need for cellular communications. As mobile devices continue to proliferate such local, device-to-device connections could become more practical.

From Technology Review:

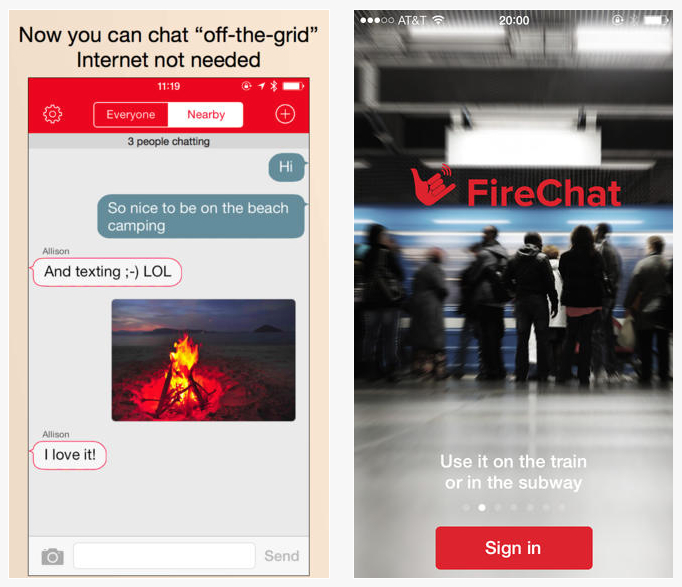

Mobile app stores are stuffed with messaging apps from WhatsApp to Tango and their many imitators. But FireChat, released last week for the iPhone, stands out. It’s the only one that can be used without cell-phone reception.

FireChat makes use of a feature Apple introduced in the latest version of its iOS mobile software, iOS7, called multipeer connectivity. This feature allows phones to connect to one another directly using Bluetooth or Wi-Fi as an alternative to the Internet. If you’re using FireChat, its “nearby” chat room lets you exchange messages with other users within 100 feet without sending data via your cellular provider.

Micha Benoliel, CEO and cofounder of startup Open Garden, which made FireChat, says the app shows how smartphones can be set free from cellular networks. He hopes to enable many more Internet-optional apps with the upcoming release of software tools that will help developers build FireChat-style apps for iPhone, or for Android, Mac, and Windows devices. “This approach is very interesting for multiplayer gaming and all kinds of communication apps,” says Benoliel.

Anthony DiPasquale, a developer with consultancy Thoughtbot, says FireChat is the only app he’s aware of that’s been built to make use of multipeer connectivity, perhaps because the feature remains unfamiliar to most Apple developers. “I hope more people start to use it soon,” he says. “It’s an awesome framework with a lot of potential. There is probably a great use for multipeer connectivity in every situation where there are people grouped together wanting to share some sort of information.” DiPasquale has dabbled in using multipeer connectivity himself, creating an experimental app that streams music from one device to several others nearby.

The new feature of iOS7 currently only supports data moving directly from one device to another, and from one device to several others. However, Open Garden’s forthcoming software will extend the feature so that data can hop between two iPhones out of range of one another via intermediary devices. That approach, known as mesh networking, is at the heart of several existing projects to create disaster-proof or community-controlled communications networks (see “Build Your Own Internet with Mobile Mesh Networking”).

Apps built to exploit such device-to-device schemes can offer security and privacy benefits over those that rely on the Internet. For example, messages sent using FireChat to nearby devices don’t pass through any systems operated by either Open Garden or a wireless carrier (although they are broadcast to all FireChat users nearby).

That means the content of a message and metadata could not be harvested from a central communications hub by an attacker or government agency. “This method of communication is immune to firewalls like the ones installed in China and North Korea,” says Mattt Thompson, a software engineer who writes the iOS and Mac development blog NSHipster. Recent revelations about large-scale surveillance of online services and the constant litany of data breaches make this a good time for apps that don’t rely on central servers, he says. “As users become more mindful of the security and privacy implications of technologies they rely on, moving in the direction of local, ad-hoc networking makes a lot of sense.”

However, peer-to-peer and mesh networking apps also come with their own risks, since an eavesdropper could gain access to local traffic just by using a device within range.

Read the entire article here.

Image courtesy of Open Garden.

Martin Cooper. You may not know that name, but you and a fair proportion of the world’s 7 billion inhabitants have surely held or dropped or prodded or cursed his offspring.

Martin Cooper. You may not know that name, but you and a fair proportion of the world’s 7 billion inhabitants have surely held or dropped or prodded or cursed his offspring.