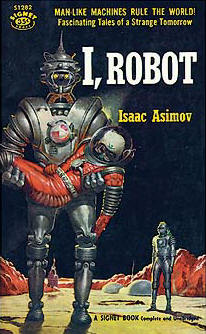

Fans of science fiction and Isaac Asimov in particular may recall his three laws of robotics:

Fans of science fiction and Isaac Asimov in particular may recall his three laws of robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Of course, technology has marched forward relentlessly since Asimov penned these guidelines in 1942. But while the ideas may seem trite and somewhat contradictory the ethical issue remains – especially as our machines become ever more powerful and independent. Though, perhaps first humans, in general, ought to agree on a set of fundamental principles for themselves.

Colin Allen for the Opinionator column reflects on the moral dilemma. He is Provost Professor of Cognitive Science and History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University, Bloomington.

[div class=attrib]From the New York Times:[end-div]

A robot walks into a bar and says, “I’ll have a screwdriver.” A bad joke, indeed. But even less funny if the robot says “Give me what’s in your cash register.”

The fictional theme of robots turning against humans is older than the word itself, which first appeared in the title of Karel ?apek’s 1920 play about artificial factory workers rising against their human overlords.

…

The prospect of machines capable of following moral principles, let alone understanding them, seems as remote today as the word “robot” is old. Some technologists enthusiastically extrapolate from the observation that computing power doubles every 18 months to predict an imminent “technological singularity” in which a threshold for machines of superhuman intelligence will be suddenly surpassed. Many Singularitarians assume a lot, not the least of which is that intelligence is fundamentally a computational process. The techno-optimists among them also believe that such machines will be essentially friendly to human beings. I am skeptical about the Singularity, and even if “artificial intelligence” is not an oxymoron, “friendly A.I.” will require considerable scientific progress on a number of fronts.

The neuro- and cognitive sciences are presently in a state of rapid development in which alternatives to the metaphor of mind as computer have gained ground. Dynamical systems theory, network science, statistical learning theory, developmental psychobiology and molecular neuroscience all challenge some foundational assumptions of A.I., and the last 50 years of cognitive science more generally. These new approaches analyze and exploit the complex causal structure of physically embodied and environmentally embedded systems, at every level, from molecular to social. They demonstrate the inadequacy of highly abstract algorithms operating on discrete symbols with fixed meanings to capture the adaptive flexibility of intelligent behavior. But despite undermining the idea that the mind is fundamentally a digital computer, these approaches have improved our ability to use computers for more and more robust simulations of intelligent agents — simulations that will increasingly control machines occupying our cognitive niche. If you don’t believe me, ask Siri.

This is why, in my view, we need to think long and hard about machine morality. Many of my colleagues take the very idea of moral machines to be a kind of joke. Machines, they insist, do only what they are told to do. A bar-robbing robot would have to be instructed or constructed to do exactly that. On this view, morality is an issue only for creatures like us who can choose to do wrong. People are morally good only insofar as they must overcome the urge to do what is bad. We can be moral, they say, because we are free to choose our own paths.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article here.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of Asimov Foundation / Wikipedia.[end-div]