Or, if you are from the UK — you can be David Brent. That is, we can all aspire to be a terrible boss. And, it’s all courtesy of the techno-enabled Uberified gig-economy.

Those of us who have a boss will identify with the mostly excruciating ritual that is the annual performance review; your work, your attitude, your personality is dissected, sliced and diced, scored, rated and ranked. However, as traumatic as this may be for you, remember that at least your boss actually interacts (usually) with you, and may actually have come to know you (somewhat), over a period of some years.

[tube]nW-bFGzNMXw[/tube]

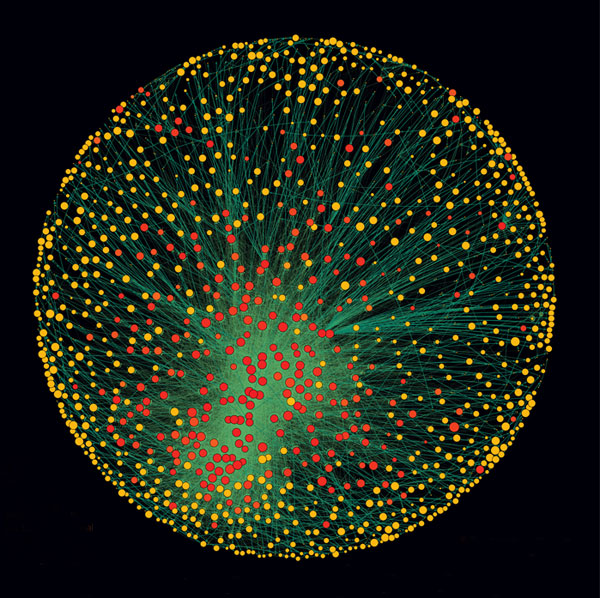

But, how would it feel to be evaluated in this way — scored and rated — by complete strangers during a fleeting interaction that may only have lasted minutes? Online social media tools make this scoring wonderfully easy and convenient — just check a box or select 1-5 stars or a thumbs up/down. Add to this the sharing / gig economy, and we now have millions of people ready (and eager) to score millions of others for waiting tables, chauffeuring a car, delivering pizza, writing an app, cleaning a house, walking your dog, mowing your lawn. And, the list grows each day. Thus, you may be an employee to any numbers of managers throughout each day — it’s just that each manager is actually one of your customers, and each customer is armed with your score.

Where will this lead us? Should we rank our partners and spouses each day, indeed, several times each day? Will we score our kids for table etiquette, manners, talk-back? Should we score the check-out employee, the bank clerk, the bus driver, barista, nurse practitioner, car mechanic, surgeon? Ugh.

But you can certainly see why corporate executives are falling over themselves to have customers anonymously score their customer-facing employees. For the process devolves power to the customer, and removes management from having to make the once tough personnel decisions. So, why not have hordes of anonymous reviews and aggregated scores from customers determine the fate of low-level service employees? This would seem to be the ultimate customer service.

Yet, by replacing the human connection between employer/customer and employee/service worker with scores and algorithms we are further commoditizing ourselves. We erode our humanity by allowing ourselves to be quantified and enumerated, and for doing the same to others, known and unknown. Having the power to score and rate another person at the press of a finger — anonymously — may make for savvy 21st century management but it makes for a colder, crueler world, which increasingly reads like a dystopian novel.

From the Verge:

Soon, you’ll be able to go to the Olive Garden and order your fettuccine alfredo from a tablet mounted to the table. After paying, you’ll rate the server.

Then you can use that tablet to hail an Uber driver, whom you’ll also rate, from one to five stars. You can take it to your Airbnb, which you’ll award one to five stars across several categories, and get a TaskRabbit or Postmates worker to pick up groceries — rate them too. Maybe you’ll check on the web developer you’ve hired through Upwork, perusing the screenshots taken automatically from her computer, and think about how you’ll rate her when the job is done. You could hire someone from Handy to clean the place before you leave. More stars.

The on-demand economy has scrambled the roles of employer and employee in ways that courts and regulators are just beginning to parse. So far, the debate has focused on whether workers should be contractors or employees, a question sometimes distilled into an argument about who’s the boss: are workers their own bosses, as the companies often claim, or is the platform their boss, policing their work through algorithms and rules?

But there’s a third party that’s often glossed over: the customer. The rating systems used by these companies have turned customers into unwitting and sometimes unwittingly ruthless middle managers, more efficient than any boss a company could hope to hire. They’re always there, working for free, hypersensitive to the smallest error. All the algorithm has to do is tally up their judgments and deactivate accordingly.

Ratings help these companies to achieve enormous scale, managing large pools of untrained contract workers without having to hire supervisors. It’s a nice arrangement for customers too, who get cheap service with a smile — even if it’s an anxious one. But for the workers, already in the precarious position of contract labor, making every customer a boss is a terrifying prospect. After all, they — we — can be entitled jerks.

“You get pretty good at kissing ass just because you have to,” an Uber driver told me. “Uber and Lyft have created this monstrous brand of customer where they expect Ritz Carlton service at McDonald’s prices.”

In March, when Judge Edward Chen denied Uber’s motion for summary judgement on the California drivers’ class action suit, he seized on the idea that ratings aren’t just a customer feedback tool — they represent a new level of monitoring, far more pervasive than any watchful boss. Customer ratings, Chen wrote, give Uber an “arguably tremendous amount of control over the ‘manner and means’ of its drivers’ performance.” Quoting from Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, he wrote that a “state of conscious and permanent visibility assures the automatic functioning of power.”

Starting with Ebay, rating systems have typically been described as way of establishing trust between strangers. Some commentators go so far as to say ratings are more effective than government regulation. “Uber and Airbnb are in fact some of the most regulated ecosystems in the world,” said Joshua Gans, an economist at the University of Toronto, at an FTC workshop earlier this year. Rather than a single certification before you can begin work, everyone is regulated constantly through a system of mutually assured judgment.

Certainly customers sometimes have awful experiences — reckless driving, creepy comments — and the rating system can help report them. But when it comes to policing dangerous behavior, most of these platforms have come to rely not on ratings but on traditional safety measures — identity verification, background checks, and the knowledge that any illegal actions can be investigated and enforced through the tracking devices every worker carries. We can’t rate for criminal histories, poor training, or negligent car maintenance.

So what do we rate for? We rate for the routes drivers take, for price fluctuations beyond their control, for slow traffic, for refusing to speed, for talking too much or too little, for failing to perform large tasks unrealistically quickly, for the food being cold when they delivered it, for telling us that, No, we can’t bring beer in the car and put our friend in the trunk — really, for any reason at all, including subconscious biases about race or gender, a proven problem on many crowdsourced platforms. This would be a nuisance if feedback were just feedback, but ratings have become the primary metric in automated systems determining employment. If you imagine the things customers rate down for as firing decisions in a traditional workplace, they look capricious and harsh. It’s a strange amount of power for customers to hold, all the more so considering that many don’t know they wield it.

Sometimes, as in Uber’s system, workers have the opportunity to rate customers back. An Uber spokesperson told me that, “Uber’s priority is to connect you with a safe, reliable ride — no matter who you are, where you’re coming from, or where you’re going. Achieving that goal for our community means maintaining an environment of mutual accountability and respect. We want everyone to have a great ride, every time, and two-way feedback is one of the many ways we work to make that possible. “

Read more here.

Video: The Prisoner – I’m not a number, I’m a free man! 1967. Courtesy: Patrick McGoohan / ITC Entertainment.

“Innovate or die” goes the business mantra. Embrace creativity or you and your company will fall by the wayside and wither into insignificance.

“Innovate or die” goes the business mantra. Embrace creativity or you and your company will fall by the wayside and wither into insignificance.

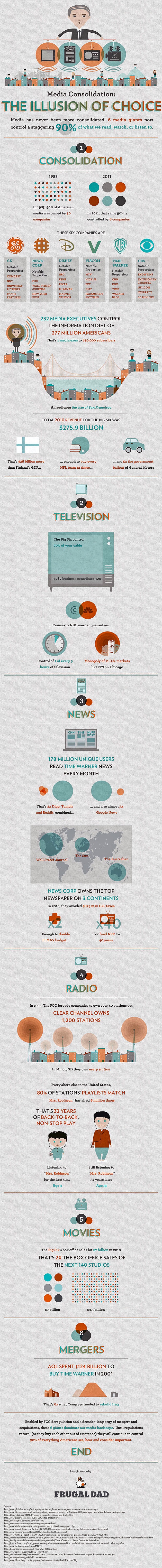

Blame corporate euphemisms and branding for the obfuscation of everyday things. More sinister yet, is the constant re-working of names for our ever increasingly processed foodstuffs. Only last year as several influential health studies pointed towards the detrimental health effects of high fructose corn syrup (HFC) did the food industry act, but not by removing copious amounts of the addictive additive from many processed foods. Rather, the industry attempted to re-brand HFC as “corn sugar”. And, now on to the battle over “soylent pink” also known as “pink slim”.

Blame corporate euphemisms and branding for the obfuscation of everyday things. More sinister yet, is the constant re-working of names for our ever increasingly processed foodstuffs. Only last year as several influential health studies pointed towards the detrimental health effects of high fructose corn syrup (HFC) did the food industry act, but not by removing copious amounts of the addictive additive from many processed foods. Rather, the industry attempted to re-brand HFC as “corn sugar”. And, now on to the battle over “soylent pink” also known as “pink slim”. A fascinating case study shows how Microsoft failed its employees through misguided HR (human resources) policies that pitted colleague against colleague.

A fascinating case study shows how Microsoft failed its employees through misguided HR (human resources) policies that pitted colleague against colleague.

The last couple of decades has seen some remarkable cases of corporate excess and corruption. The deep-rooted human inclinations toward greed, telling falsehoods and exhibiting questionable ethics can probably be traced to the dawn of bipedalism. However, in more recent times we have seen misdeeds particularly in the business world grow in their daring, scale and impact.

The last couple of decades has seen some remarkable cases of corporate excess and corruption. The deep-rooted human inclinations toward greed, telling falsehoods and exhibiting questionable ethics can probably be traced to the dawn of bipedalism. However, in more recent times we have seen misdeeds particularly in the business world grow in their daring, scale and impact.

Forget art school, engineering school, law school and B-school (business). For wannabe innovators the current place to be is D-school. Design school, that is.

Forget art school, engineering school, law school and B-school (business). For wannabe innovators the current place to be is D-school. Design school, that is.