Researchers at Imperial College, London recently posed an intriguing question and have since developed a cool experiment to test it. Does artistic endeavor, such as music, follow the same principles of evolutionary selection in biology, as described by Darwin? That is, does the funkiest survive? Though, one has to wonder what the eminent scientist would have thought about some recent fusion of rap / dubstep / classical.

Researchers at Imperial College, London recently posed an intriguing question and have since developed a cool experiment to test it. Does artistic endeavor, such as music, follow the same principles of evolutionary selection in biology, as described by Darwin? That is, does the funkiest survive? Though, one has to wonder what the eminent scientist would have thought about some recent fusion of rap / dubstep / classical.

From the Guardian:

There were some funky beats at Imperial College London on Saturday at its annual science festival. As well as opportunities to create bogeys, see robots dance and try to get physics PhD students to explain their wacky world, this fascinating event included the chance to participate in a public game-like experiment called DarwinTunes.

Participants select tunes and “mate” them with other tunes to create musical offspring: if the offspring are in turn selected by other players, they “survive” and get the chance to reproduce their musical DNA. The experiment is online – you too can try to immortalise your selfish musical genes.

It is a model of evolution in practice that raises fascinating questions about culture and nature. These questions apply to all the arts, not just to dance beats. How does “cultural evolution” work? How close is the analogy between Darwin’s well-proven theory of evolution in nature and the evolution of art, literature and music?

The idea of cultural evolution was boldly defined by Jacob Bronowski as our fundamental human ability “not to accept the environment but to change it”. The moment the first stone tools appeared in Africa, about 2.5m years ago, a new, faster evolution, that of human culture, became visible on Earth: from cave paintings to the Renaissance, from Galileo to the 3D printer, this cultural evolution has advanced at breathtaking speed compared with the massive periods of time it takes nature to evolve new forms.

In DarwinTunes, cultural evolution is modelled as what the experimenters call “the survival of the funkiest”. Pulsing dance beats evolve through selections made by participants, and the music (it is claimed) becomes richer through this process of selection. Yet how does the model really correspond to the story of culture?

One way Darwin’s laws of nature apply to visual art is in the need for every successful form to adapt to its environment. In the forests of west and central Africa, wood carving was until recent times a flourishing art form. In the islands of Greece, where marble could be quarried easily, stone sculpture was more popular. In the modern technological world, the things that easily come to hand are not wood or stone but manufactured products and media images – so artists are inclined to work with the readymade.

At first sight, the thesis of DarwinTunes is a bit crude. Surely it is obvious that artists don’t just obey the selections made by their audience – that is, their consumers. To think they do is to apply the economic laws of our own consumer society across all history. Culture is a lot funkier than that.

Yet just because the laws of evolution need some adjustment to encompass art, that does not mean art is a mysterious spiritual realm impervious to scientific study. In fact, the evolution of evolution – the adjustments made by researchers to Darwin’s theory since it was unveiled in the Victorian age – offers interesting ways to understand culture.

One useful analogy between art and nature is the idea of punctuated equilibrium, introduced by some evolutionary scientists in the 1970s. Just as species may evolve not through a constant smooth process but by spectacular occasional leaps, so the history of art is punctuated by massively innovative eras followed by slower, more conventional periods.

Read the entire story here.

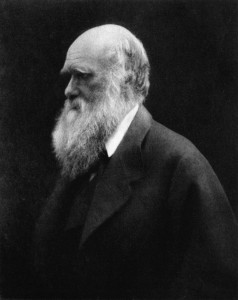

Image: Charles Darwin, 1868, photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

There is a certain school of thought that asserts that scientific genius is a thing of the past. After all, we haven’t seen the recent emergence of pivotal talents such as Galileo, Newton, Darwin or Einstein. Is it possible that fundamentally new ways to look at our world — that a new mathematics or a new physics is no longer possible?

There is a certain school of thought that asserts that scientific genius is a thing of the past. After all, we haven’t seen the recent emergence of pivotal talents such as Galileo, Newton, Darwin or Einstein. Is it possible that fundamentally new ways to look at our world — that a new mathematics or a new physics is no longer possible? British voters may recall Screaming Lord Sutch, 3rd Earl of Harrow, of the Official Monster Raving Loony Party, who ran in over 40 parliamentary elections during the 1980s and 90s. He never won, but garnered a respectable number of votes and many fans (he was also a musician).

British voters may recall Screaming Lord Sutch, 3rd Earl of Harrow, of the Official Monster Raving Loony Party, who ran in over 40 parliamentary elections during the 1980s and 90s. He never won, but garnered a respectable number of votes and many fans (he was also a musician). [div class=attrib]From Discover:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Discover:[end-div]