Professor of philosopher Shelly Kagan has an interesting take on death. After all, how bad can something be for you if you’re not alive to experience it?

Professor of philosopher Shelly Kagan has an interesting take on death. After all, how bad can something be for you if you’re not alive to experience it?

[div class=attrib]From the Chronicle:[end-div]

We all believe that death is bad. But why is death bad?

In thinking about this question, I am simply going to assume that the death of my body is the end of my existence as a person. (If you don’t believe me, read the first nine chapters of my book.) But if death is my end, how can it be bad for me to die? After all, once I’m dead, I don’t exist. If I don’t exist, how can being dead be bad for me?

People sometimes respond that death isn’t bad for the person who is dead. Death is bad for the survivors. But I don’t think that can be central to what’s bad about death. Compare two stories.

Story 1. Your friend is about to go on the spaceship that is leaving for 100 Earth years to explore a distant solar system. By the time the spaceship comes back, you will be long dead. Worse still, 20 minutes after the ship takes off, all radio contact between the Earth and the ship will be lost until its return. You’re losing all contact with your closest friend.

Story 2. The spaceship takes off, and then 25 minutes into the flight, it explodes and everybody on board is killed instantly.

Story 2 is worse. But why? It can’t be the separation, because we had that in Story 1. What’s worse is that your friend has died. Admittedly, that is worse for you, too, since you care about your friend. But that upsets you because it is bad for her to have died. But how can it be true that death is bad for the person who dies?

In thinking about this question, it is important to be clear about what we’re asking. In particular, we are not asking whether or how the process of dying can be bad. For I take it to be quite uncontroversial—and not at all puzzling—that the process of dying can be a painful one. But it needn’t be. I might, after all, die peacefully in my sleep. Similarly, of course, the prospect of dying can be unpleasant. But that makes sense only if we consider death itself to be bad. Yet how can sheer nonexistence be bad?

Maybe nonexistence is bad for me, not in an intrinsic way, like pain, and not in an instrumental way, like unemployment leading to poverty, which in turn leads to pain and suffering, but in a comparative way—what economists call opportunity costs. Death is bad for me in the comparative sense, because when I’m dead I lack life—more particularly, the good things in life. That explanation of death’s badness is known as the deprivation account.

Despite the overall plausibility of the deprivation account, though, it’s not all smooth sailing. For one thing, if something is true, it seems as though there’s got to be a time when it’s true. Yet if death is bad for me, when is it bad for me? Not now. I’m not dead now. What about when I’m dead? But then, I won’t exist. As the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus wrote: “So death, the most terrifying of ills, is nothing to us, since so long as we exist, death is not with us; but when death comes, then we do not exist. It does not then concern either the living or the dead, since for the former it is not, and the latter are no more.”

If death has no time at which it’s bad for me, then maybe it’s not bad for me. Or perhaps we should challenge the assumption that all facts are datable. Could there be some facts that aren’t?

Suppose that on Monday I shoot John. I wound him with the bullet that comes out of my gun, but he bleeds slowly, and doesn’t die until Wednesday. Meanwhile, on Tuesday, I have a heart attack and die. I killed John, but when? No answer seems satisfactory! So maybe there are undatable facts, and death’s being bad for me is one of them.

Alternatively, if all facts can be dated, we need to say when death is bad for me. So perhaps we should just insist that death is bad for me when I’m dead. But that, of course, returns us to the earlier puzzle. How could death be bad for me when I don’t exist? Isn’t it true that something can be bad for you only if you exist? Call this idea the existence requirement.

Should we just reject the existence requirement? Admittedly, in typical cases—involving pain, blindness, losing your job, and so on—things are bad for you while you exist. But maybe sometimes you don’t even need to exist for something to be bad for you. Arguably, the comparative bads of deprivation are like that.

Unfortunately, rejecting the existence requirement has some implications that are hard to swallow. For if nonexistence can be bad for somebody even though that person doesn’t exist, then nonexistence could be bad for somebody who never exists. It can be bad for somebody who is a merely possible person, someone who could have existed but never actually gets born.

t’s hard to think about somebody like that. But let’s try, and let’s call him Larry. Now, how many of us feel sorry for Larry? Probably nobody. But if we give up on the existence requirement, we no longer have any grounds for withholding our sympathy from Larry. I’ve got it bad. I’m going to die. But Larry’s got it worse: He never gets any life at all.

Moreover, there are a lot of merely possible people. How many? Well, very roughly, given the current generation of seven billion people, there are approximately three million billion billion billion different possible offspring—almost all of whom will never exist! If you go to three generations, you end up with more possible people than there are particles in the known universe, and almost none of those people get to be born.

If we are not prepared to say that that’s a moral tragedy of unspeakable proportions, we could avoid this conclusion by going back to the existence requirement. But of course, if we do, then we’re back with Epicurus’ argument. We’ve really gotten ourselves into a philosophical pickle now, haven’t we? If I accept the existence requirement, death isn’t bad for me, which is really rather hard to believe. Alternatively, I can keep the claim that death is bad for me by giving up the existence requirement. But then I’ve got to say that it is a tragedy that Larry and the other untold billion billion billions are never born. And that seems just as unacceptable.

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image: Still photograph from Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal”. Courtesy of the Guardian.[end-div]

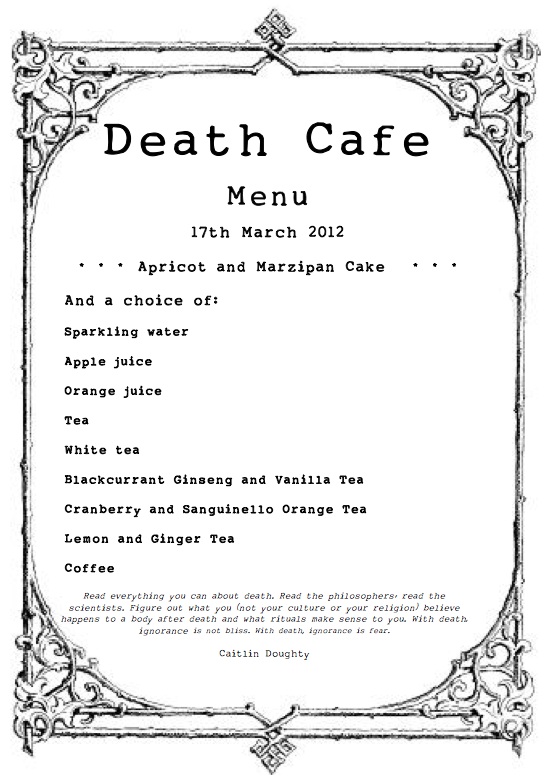

“Death Cafe” sounds like the name of a group of alternative musicians from Denmark. But it’s not. Its rather more literal definition is a coffee shop where customers go to talk about death over a cup of earl grey tea or double shot espresso. And, while it’s not displacing Starbucks (yet), death cafes are a growing trend in Europe, first inspired by the pop-up Cafe Mortels of Switzerland.

“Death Cafe” sounds like the name of a group of alternative musicians from Denmark. But it’s not. Its rather more literal definition is a coffee shop where customers go to talk about death over a cup of earl grey tea or double shot espresso. And, while it’s not displacing Starbucks (yet), death cafes are a growing trend in Europe, first inspired by the pop-up Cafe Mortels of Switzerland. Professor of philosopher Shelly Kagan has an interesting take on death. After all, how bad can something be for you if you’re not alive to experience it?

Professor of philosopher Shelly Kagan has an interesting take on death. After all, how bad can something be for you if you’re not alive to experience it?

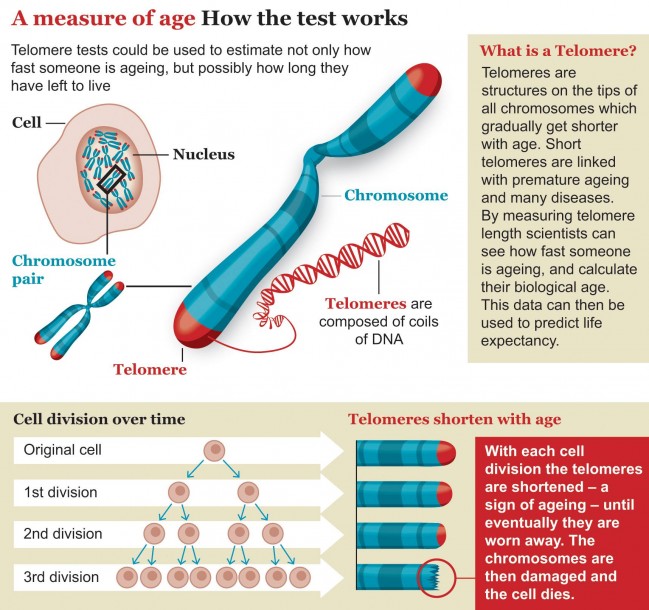

Would you like to know when you will die?

Would you like to know when you will die? Ushering in our week of articles focused mostly on death and loss is a classic piece by Welshman, Dylan Thomas. Although Thomas’ literary legacy is colored by his legendary drinking and philandering, many critics now seem to agree that his poetry belongs in the same class as that of W.H. Auden.

Ushering in our week of articles focused mostly on death and loss is a classic piece by Welshman, Dylan Thomas. Although Thomas’ literary legacy is colored by his legendary drinking and philandering, many critics now seem to agree that his poetry belongs in the same class as that of W.H. Auden.

Accumulating likes, collecting followers and quantifying one’s friends online is serious business. If you don’t have more than a couple of hundred professional connections in your LinkedIn profile or at least twice that number of “friends” through Facebook or ten times that volume of Twittering followers, you’re most likely to be a corporate wallflower, a social has-been.

Accumulating likes, collecting followers and quantifying one’s friends online is serious business. If you don’t have more than a couple of hundred professional connections in your LinkedIn profile or at least twice that number of “friends” through Facebook or ten times that volume of Twittering followers, you’re most likely to be a corporate wallflower, a social has-been.