The era of truly personalized medicine and treatment plans may still be a fair way off, but thanks to big data initiatives predictive and preventative health is making significant progress. This bodes well for over-stretched healthcare systems, medical professionals, and those who need care and/or pay for it.

That said, it is useful to keep in mind how similar data in other domains such as shopping travel and media, has been delivering personalized content and services for quite some time. So, healthcare information technology certainly lags, where it should be leading. One single answer may be impossible to agree upon. However, it is encouraging to see the healthcare and medical information industries catching up.

From Technology Review:

On the ground floor of the Mount Sinai Medical Center’s new behemoth of a research and hospital building in Manhattan, rows of empty black metal racks sit waiting for computer processors and hard disk drives. They’ll house the center’s new computing cluster, adding to an existing $3 million supercomputer that hums in the basement of a nearby building.

The person leading the design of the new computer is Jeff Hammerbacher, a 30-year-old known for being Facebook’s first data scientist. Now Hammerbacher is applying the same data-crunching techniques used to target online advertisements, but this time for a powerful engine that will suck in medical information and spit out predictions that could cut the cost of health care.

With $3 trillion spent annually on health care in the U.S., it could easily be the biggest job for “big data” yet. “We’re going out on a limb—we’re saying this can deliver value to the hospital,” says Hammerbacher.

Mount Sinai has 1,406 beds plus a medical school and treats half a million patients per year. Increasingly, it’s run like an information business: it’s assembled a biobank with 26,735 patient DNA and plasma samples, it finished installing a $120 million electronic medical records system this year, and it has been spending heavily to recruit computing experts like Hammerbacher.

It’s all part of a “monstrously large bet that [data] is going to matter,” says Eric Schadt, the computational biologist who runs Mount Sinai’s Icahn Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology, where Hammerbacher is based, and who was himself recruited from the gene sequencing company Pacific Biosciences two years ago.

Mount Sinai hopes data will let it succeed in a health-care system that’s shifting dramatically. Perversely, because hospitals bill by the procedure, they tend to earn more the sicker their patients become. But health-care reform in Washington is pushing hospitals toward a new model, called “accountable care,” in which they will instead be paid to keep people healthy.

Mount Sinai is already part of an experiment that the federal agency overseeing Medicare has organized to test these economic ideas. Last year it joined 250 U.S. doctor’s practices, clinics, and other hospitals in agreeing to track patients more closely. If the medical organizations can cut costs with better results, they’ll share in the savings. If costs go up, they can face penalties.

The new economic incentives, says Schadt, help explain the hospital’s sudden hunger for data, and its heavy spending to hire 150 people during the last year just in the institute he runs. “It’s become ‘Hey, use all your resources and data to better assess the population you are treating,’” he says.

One way Mount Sinai is doing that already is with a computer model where factors like disease, past hospital visits, even race, are used to predict which patients stand the highest chance of returning to the hospital. That model, built using hospital claims data, tells caregivers which chronically ill people need to be showered with follow-up calls and extra help. In a pilot study, the program cut readmissions by half; now the risk score is being used throughout the hospital.

Hammerbacher’s new computing facility is designed to supercharge the discovery of such insights. It will run a version of Hadoop, software that spreads data across many computers and is popular in industries, like e-commerce, that generate large amounts of quick-changing information.

Patient data are slim by comparison, and not very dynamic. Records get added to infrequently—not at all if a patient visits another hospital. That’s a limitation, Hammerbacher says. Yet he hopes big-data technology will be used to search for connections between, say, hospital infections and the DNA of microbes present in an ICU, or to track data streaming in from patients who use at-home monitors.

One person he’ll be working with is Joel Dudley, director of biomedical informatics at Mount Sinai’s medical school. Dudley has been running information gathered on diabetes patients (like blood sugar levels, height, weight, and age) through an algorithm that clusters them into a weblike network of nodes. In “hot spots” where diabetic patients appear similar, he’s then trying to find out if they share genetic attributes. That way DNA information might add to predictions about patients, too.

A goal of this work, which is still unpublished, is to replace the general guidelines doctors often use in deciding how to treat diabetics. Instead, new risk models—powered by genomics, lab tests, billing records, and demographics—could make up-to-date predictions about the individual patient a doctor is seeing, not unlike how a Web ad is tailored according to who you are and sites you’ve visited recently.

That is where the big data comes in. In the future, every patient will be represented by what Dudley calls “large dossier of data.” And before they are treated, or even diagnosed, the goal will be to “compare that to every patient that’s ever walked in the door at Mount Sinai,” he says. “[Then] you can say quantitatively what’s the risk for this person based on all the other patients we’ve seen.”

Read the entire article here.

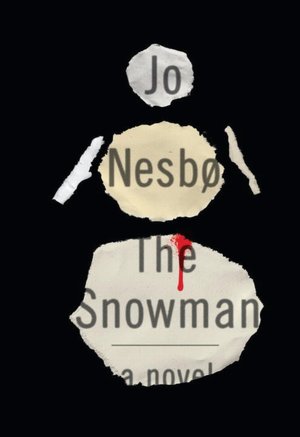

The title could be mistaken for a dark and violent crime novel from the likes of (Stieg) Larrson, Nesbø, Sjöwall-Wahlöö, or Henning Mankell. But, this story is somewhat more mundane, though much more consequential. It’s a story about a Swedish cancer killer.

The title could be mistaken for a dark and violent crime novel from the likes of (Stieg) Larrson, Nesbø, Sjöwall-Wahlöö, or Henning Mankell. But, this story is somewhat more mundane, though much more consequential. It’s a story about a Swedish cancer killer.

New research suggests that women feel pain more intensely than men.

New research suggests that women feel pain more intensely than men.