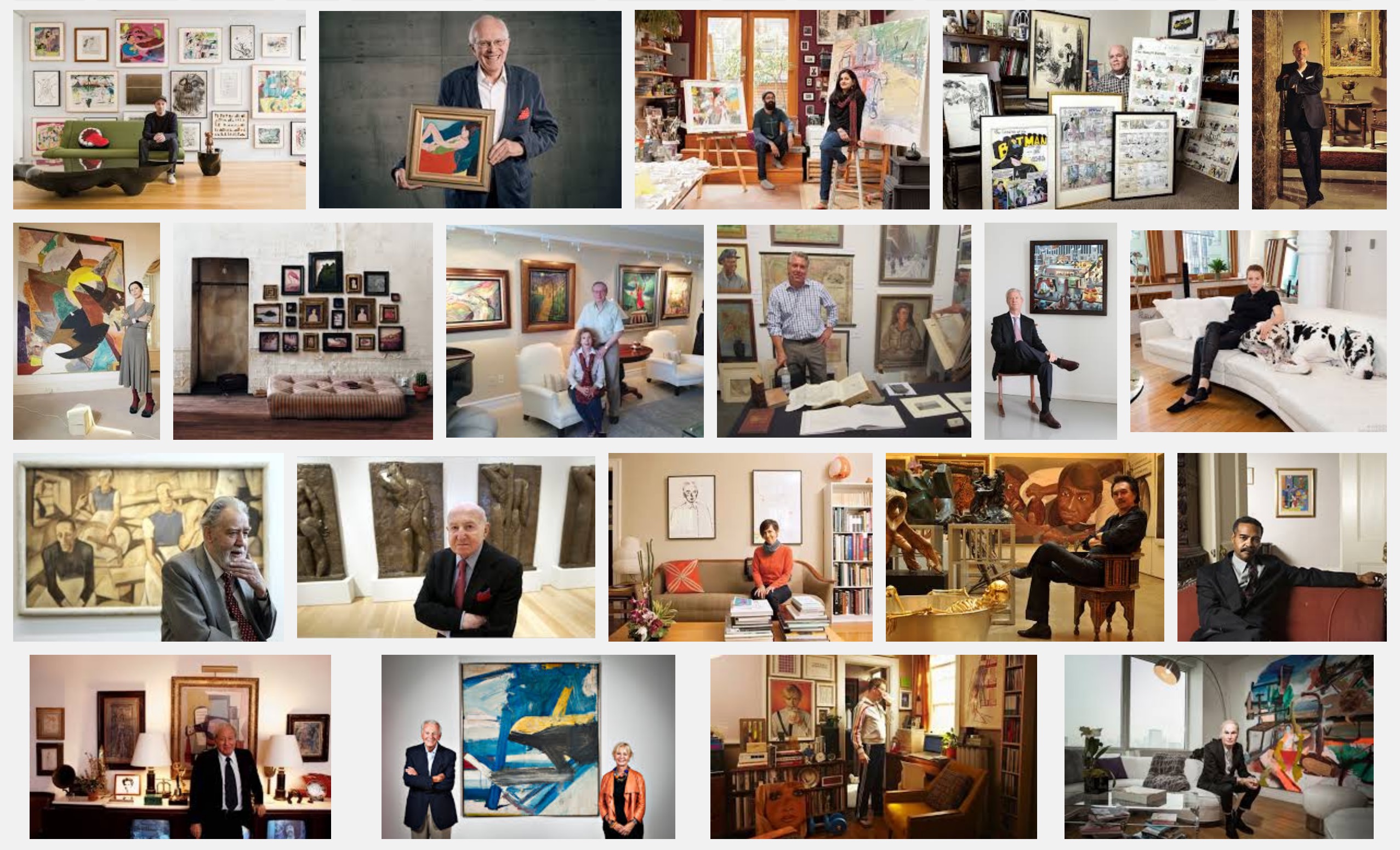

Art collectors have probably been around since humans first started scribbling, painting, casting and throwing (clay). Some collect exclusively for financial gain or to reduce their tax bills. Others accumulate works to signal their worth and superiority over their neighbors or to the world. Still others do so because of a personal affinity to the artist. A small number use art to launder money. Some even collect art because of emotional attachment to the art itself.

A new book entitled Possession: The Curious History of Private Collectors by Erin Thompson, delves into the art world and examines the curious mind of the art collector. Thompson is assistant professor of art crime at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York. Parts of her recent essay for Aeon are excerpted below.

From Aeon:

The oil billionaire J Paul Getty was famously miserly. He installed a payphone in his mansion in Surrey, England, to stop visitors from making long-distance calls. He refused to pay ransom for a kidnapped grandson for so long that the frustrated kidnappers sent Getty his grandson’s ear in the mail. Yet he spent millions of dollars on art, and millions more to build the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. He called himself ‘an apparently incurable art-collecting addict’, and noted that he had vowed to stop collecting several times, only to suffer ‘massive relapses’. Fearful of airplanes and too busy to take the time to sail to California from his adopted hometown of London, he never even visited the museum his money had filled.

Getty is only one of the many people through history who have gone to great lengths to collect art – searching, spending, and even stealing to satisfy their cravings. But what motivates these collectors?

Debates about why people collect art date back at least to the first century CE. The Roman rhetorician Quintilian claimed that those who professed to admire what he considered to be the primitive works of the painter Polygnotus were motivated by ‘an ostentatious desire to seem persons of superior taste’. Quintilian’s view still finds many supporters.

Another popular explanation for collecting – financial gain – cannot explain why collectors go to such lengths. Of course, many people buy art for financial reasons. You can resell works, sometimes reaping enormous profit. You can get large tax deductions for donating art to museums – so large that the federal government has seized thousands of looted antiquities that were smuggled into the United States just so that they could be donated with inflated valuations to knock money off the donors’ tax bills. Meanwhile, some collectors have figured out how to keep their artworks close at hand while still getting a tax deduction by donating them to private museums that they’ve set up on their own properties. More nefariously, some ‘collectors’ buy art as a form of money laundering, since it is far easier to move art than cash between countries without scrutiny.

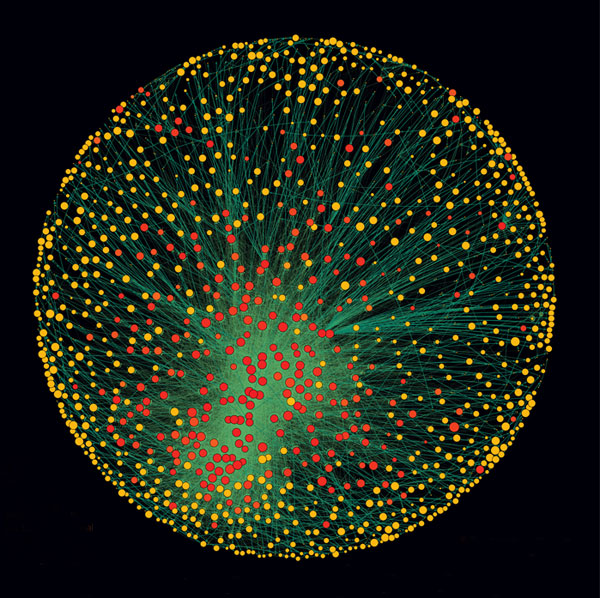

But most collectors have little regard for profit. For them, art is important for other reasons. The best way to understand the underlying drive of art collecting is as a means to create and strengthen social bonds, and as a way for collectors to communicate information about themselves and the world within these new networks. Think about when you were a child, making friends with the new kid on the block by showing off your shoebox full of bird feathers or baseball cards. You were forming a new link in your social network and communicating some key pieces of information about yourself (I’m a fan of orioles/the Orioles). The art collector conducting dinner party guests through her private art gallery has the same goals – telling new friends about herself.

People tend to imagine collectors as highly competitive, but that can prove wrong too. Serious art collectors often talk about the importance not of competition but of the social networks and bonds with family, friends, scholars, visitors and fellow collectors created and strengthened by their collecting. The way in which collectors describe their first purchases often reveals the central role of the social element. Only very rarely do collectors attribute their collecting to a solo encounter with an artwork, or curiosity about the past, or the reading of a textual source. Instead, they almost uniformly give credit to a friend or family member for sparking their interest, usually through encountering and discussing a specific artwork together. A collector showing off her latest finds to her children is doing the same thing as a sports fan gathering the kids to watch the game: reinforcing family bonds through a shared interest.

Read the entire article below.

Image courtesy of Google Search.

We excerpt below a fascinating article from the WSJ on the increasingly incestuous and damaging relationship between the finance industry and our political institutions.

We excerpt below a fascinating article from the WSJ on the increasingly incestuous and damaging relationship between the finance industry and our political institutions. The last couple of decades has seen some remarkable cases of corporate excess and corruption. The deep-rooted human inclinations toward greed, telling falsehoods and exhibiting questionable ethics can probably be traced to the dawn of bipedalism. However, in more recent times we have seen misdeeds particularly in the business world grow in their daring, scale and impact.

The last couple of decades has seen some remarkable cases of corporate excess and corruption. The deep-rooted human inclinations toward greed, telling falsehoods and exhibiting questionable ethics can probably be traced to the dawn of bipedalism. However, in more recent times we have seen misdeeds particularly in the business world grow in their daring, scale and impact.