Mork returned to Ork this weekend; sadly, his creator Robin Williams passed away on August 11, 2014. He was 63. His unique comic genius will be sorely missed.

From NYT:

Some years ago, at a party at the Cannes Film Festival, I was leaning against a rail watching a fireworks display when I heard a familiar voice behind me. Or rather, at least a dozen voices, punctuating the offshore explosions with jokes, non sequiturs and off-the-wall pop-cultural, sexual and political references.

There was no need to turn around: The voices were not talking directly to me and they could not have belonged to anyone other than Robin Williams, who was extemporizing a monologue at least as pyrotechnically amazing as what was unfolding against the Mediterranean sky. I’m unable to recall the details now, but you can probably imagine the rapid-fire succession of accents and pitches — macho basso, squeaky girly, French, Spanish, African-American, human, animal and alien — entangling with curlicues of self-conscious commentary about the sheer ridiculousness of anyone trying to narrate explosions of colored gunpowder in real time.

Part of the shock of his death on Monday came from the fact that he had been on — ubiquitous, self-reinventing, insistently present — for so long. On Twitter, mourners dated themselves with memories of the first time they had noticed him. For some it was the movie “Aladdin.” For others “Dead Poets Society” or “Mrs. Doubtfire.” I go back even further, to the “Mork and Mindy” television show and an album called “Reality — What a Concept” that blew my eighth-grade mind.

Back then, it was clear that Mr. Williams was one of the most explosively, exhaustingly, prodigiously verbal comedians who ever lived. The only thing faster than his mouth was his mind, which was capable of breathtaking leaps of free-associative absurdity. Janet Maslin, reviewing his standup act in 1979, cataloged a tumble of riffs that ranged from an impression of Jacques Cousteau to “an evangelist at the Disco Temple of Comedy,” to Truman Capote Jr. at “the Kindergarten of the Stars” (whatever that was). “He acts out the Reader’s Digest condensed version of ‘Roots,’ ” Ms. Maslin wrote, “which lasts 15 seconds in its entirety. He improvises a Shakespearean-sounding epic about the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster, playing all the parts himself, including Einstein’s ghost.” (That, or something like it, was a role he would reprise more than 20 years later in Steven Spielberg’s “A.I.”)

Read the entire article here.

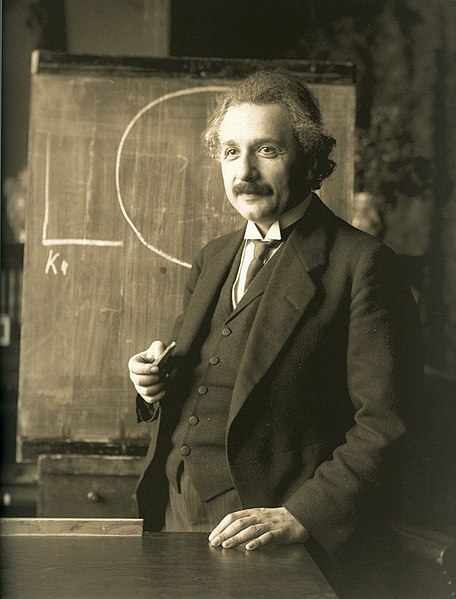

Image courtesy of Google Search.

There is a certain school of thought that asserts that scientific genius is a thing of the past. After all, we haven’t seen the recent emergence of pivotal talents such as Galileo, Newton, Darwin or Einstein. Is it possible that fundamentally new ways to look at our world — that a new mathematics or a new physics is no longer possible?

There is a certain school of thought that asserts that scientific genius is a thing of the past. After all, we haven’t seen the recent emergence of pivotal talents such as Galileo, Newton, Darwin or Einstein. Is it possible that fundamentally new ways to look at our world — that a new mathematics or a new physics is no longer possible?