The process through which an artist finds fortune and fame is a complex one, though to many of us — even those who have spent some time within the art world — it seems rather random and obscure. Raw talent alone will only carry an artist up the first rungs of the ladder of success. To gain the upper reaches requires and modicum of luck and lots of communication, connections, sales and marketing.

Unfortunately, for those artists who seek only to create and show their works (and perhaps even sell a few), the world of art is very much a business. It is driven by money, personality (of the artist or her proxies) and market power of a select few galleries, curators, critics, collectors, investors, and brokers. So, just like any other capitalist adventure the art market can be manoeuvered and manipulated. As a result, a few artists become global superstars, while still living, their art taking on a financial life of its own; the remaining 99.999 percent — well, they’ll have to hold on to their day-jobs.

From WSJ:

Next month, British artist Damien Hirst—a former superstar whose prices plummeted during the recession—could pull off an unthinkable feat: By opening a free museum, called the Newport Street Gallery, in south London to display his private collection of other artists’ works, Mr. Hirst could salvage his own career.

Just as the new museum opens, an independent but powerful set of dealers, collectors and art advisers are quietly betting that a surge of interest in Mr. Hirst’s new endeavor could spill over into higher sales for his art. Some, like New York dealer Jose Mugrabi, are stockpiling Hirsts in hopes of reselling them for later profits, believing a fresh generation of art collectors will walk away wanting to buy their own Hirsts. Mr. Mugrabi, who helped mount successful comeback campaigns in the past for Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Richard Prince, said he owns 120 pieces by Mr. Hirst, including $33 million of art he bought directly from the artist’s studio three months ago.

Other dealers, such as Pilar Ordovas, are organizing gallery shows that place Mr. Hirst’s work alongside still-popular artists, angling for a beneficial comparison.

New York art adviser Kim Heirston, whose clients include Naples collector Massimo Lauro, said she has been scouring for Hirsts at fairs and auctions alike. “I’m telling anybody who will listen to buy him because Damien Hirst is here to stay,” Ms. Heirston said.

If successful, their efforts could offer a real-time glimpse into the market-timing moves of the art-world elite, where the tastes of a few can still sway the opinions of the masses. Few marketplaces are as changeable as contemporary art. This is a realm where price levels for an artist can be catapulted in a matter of minutes by a handful of collectors in an auction. Those same champions can then turn around the following season and dump their stakes in the same artist, dismissing him as a sellout. Like fashion, the roster of coveted artists is continually being reshuffled in subtle ways.

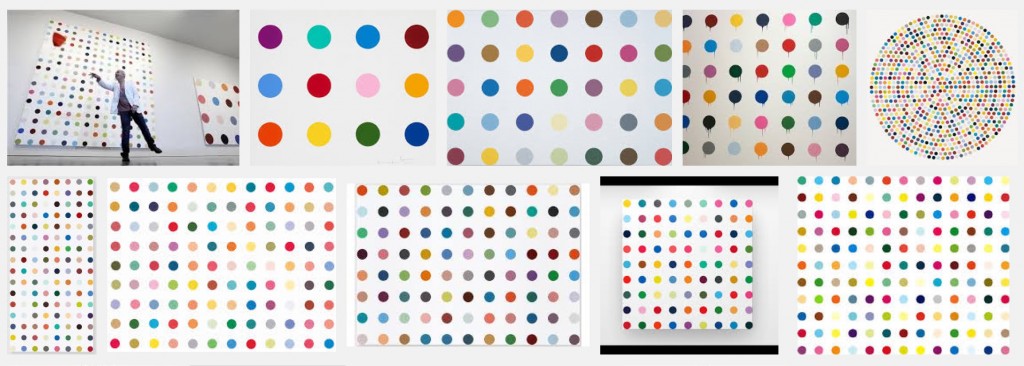

Most artists with lengthy careers have seasons of ebb and flow, and collectors who sync their buying and selling can profit accordingly, experts say. Before the recession, Mr. Hirst, age 50, was an art-world darling, the leader of London’s 1990s generation of so-called Young British Artists who explored ideas about life and death in provocative, outsize ways. He is best known for covering canvases in dead butterflies and polka dots whose rainbow hues he color-coded to match chemical compounds found in drugs.

During the market’s last peak, collectors paid as much as $19 million at auction for his artworks, and he staffed multiple studios throughout the U.K. with as many as 100 studio assistants to help produce his works. Mr. Hirst is reportedly worth an estimated $350 million, thanks to his art sales but also his skill as a businessman, amassing an empire of real estate holdings in the U.K. and elsewhere. He also co-founded a publishing company called Other Criteria in 2005 that publishes art books, artist-designed clothing and prints of his works, as well as other emerging artists.

But his star fell sharply after he committed an art-world taboo by bypassing conventional sales channels—selling works slowly through galleries—and auctioned off nearly $200 million of his work directly at Sotheby’s in 2008. While the sale was successful and proved his popularity, it became his undoing. He irked his galleries and some longtime collectors, who felt he had flooded his own marketplace for a singular payout. These days, it’s “much riskier” to trade a Hirst at auction than it was a decade ago, according to Michael Moses, co-founder of an auction tracking firm called Beautiful Asset Advisors. Collectors who bought and resold his works since 2005 have mainly suffered losses, Mr. Moses added.

Read the entire story here.

Image: A collection of some of Damien Hirst’s “dot” works. Courtesy of Google Search.