Why do we listen to sad music, and how is it that sad music can be as attractive as its lighter, happier cousin? After all we tend to want to steer clear of sad situations. New research suggests that it is more complex than a desire for catharsis, rather there is a disconnect between the felt emotion and the perceived emotion.

Why do we listen to sad music, and how is it that sad music can be as attractive as its lighter, happier cousin? After all we tend to want to steer clear of sad situations. New research suggests that it is more complex than a desire for catharsis, rather there is a disconnect between the felt emotion and the perceived emotion.

From the New York Times:

Sadness is an emotion we usually try to avoid. So why do we choose to listen to sad music?

Musicologists and philosophers have wondered about this. Sad music can induce intense emotions, yet the type of sadness evoked by music also seems pleasing in its own way. Why? Aristotle famously suggested the idea of catharsis: that by overwhelming us with an undesirable emotion, music (or drama) somehow purges us of it.

But what if, despite their apparent similarity, sadness in the realm of artistic appreciation is not the same thing as sadness in everyday life?

In a study published this summer in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, my colleagues and I explored the idea that “musical emotion” encompasses both the felt emotion that the music induces in the listener and the perceived emotion that the listener judges the music to express. By isolating these two overlapping sets of emotions and observing how they related to each other, we hoped to gain a better understanding of sad music.

Forty-four people served as participants in our experiment. We asked them to listen to one of three musical excerpts of approximately 30 seconds each. The excerpts were from Mikhail Glinka’s “La Séparation” (F minor), Felix Blumenfeld’s “Sur Mer” (G minor) and Enrique Granados’s “Allegro de Concierto” (C sharp major, though the excerpt was in G major, which we transposed to G minor).

We were interested in the minor key because it is canonically associated with sad music, and we steered clear of well-known compositions to avoid interference from any personal memories related to the pieces.

(Our participants were more or less split between men and women, as well as between musicians and nonmusicians, though these divisions turned out to be immaterial to our findings.)

A participant would listen to an excerpt and then answer a question about his felt emotions: “How did you feel when listening to this music?” Then he would listen to a “happy” version of the excerpt — i.e., transposed into the major key — and answer the same question. Next he would listen to the excerpt, again in both sad and happy versions, each time answering a question about other listeners that was designed to elicit perceived emotion: “How would normal people feel when listening to this music?”

(This is a slight simplification: in the actual study, the order in which the participant answered questions about felt and perceived emotion, and listened to sad and happy excerpts, varied from participant to participant.)

Our participants answered each question by rating 62 emotion-related descriptive words and phrases — from happy to sad, from bouncy to solemn, from heroic to wistful — on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

We found, as anticipated, that felt emotion did not correspond exactly to perceived emotion. Although the sad music was both perceived and felt as “tragic” (e.g., gloomy, meditative and miserable), the listeners did not actually feel the tragic emotion as much as they perceived it. Likewise, when listening to sad music, the listeners felt more “romantic” emotion (e.g., fascinated, dear and in love) and “blithe” emotion (e.g., merry, animated and feel like dancing) than they perceived.

Read the entire article here.

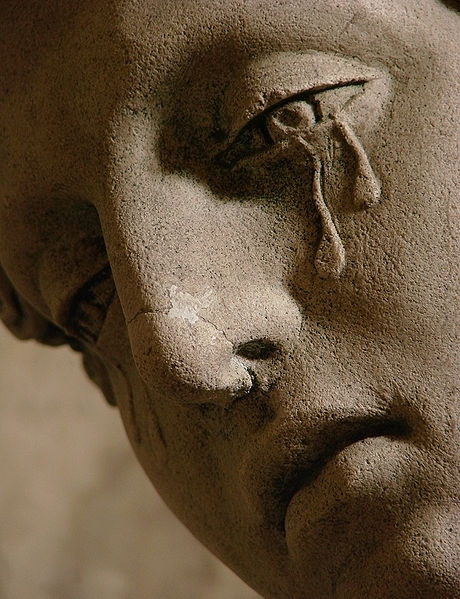

Image: Detail of Marie-Magdalene, Entombment of Christ, 1672. Courtesy of Wikipedia.