Luddites and technophobes rejoice, paper-bound books may be with us for quite some time. And, there may be some genuinely scientific reasons why physical books will remain. Recent research shows that people learn more effectively when reading from paper versus its digital offspring.

From Wired:

Paper books were supposed to be dead by now. For years, information theorists, marketers, and early adopters have told us their demise was imminent. Ikea even redesigned a bookshelf to hold something other than books. Yet in a world of screen ubiquity, many people still prefer to do their serious reading on paper.

Count me among them. When I need to read deeply—when I want to lose myself in a story or an intellectual journey, when focus and comprehension are paramount—I still turn to paper. Something just feels fundamentally richer about reading on it. And researchers are starting to think there’s something to this feeling.

To those who see dead tree editions as successors to scrolls and clay tablets in history’s remainder bin, this might seem like literary Luddism. But I e-read often: when I need to copy text for research or don’t want to carry a small library with me. There’s something especially delicious about late-night sci-fi by the light of a Kindle Paperwhite.

What I’ve read on screen seems slippery, though. When I later recall it, the text is slightly translucent in my mind’s eye. It’s as if my brain better absorbs what’s presented on paper. Pixels just don’t seem to stick. And often I’ve found myself wondering, why might that be?

The usual explanation is that internet devices foster distraction, or that my late-thirty-something brain isn’t that of a true digital native, accustomed to screens since infancy. But I have the same feeling when I am reading a screen that’s not connected to the internet and Twitter or online Boggle can’t get in the way. And research finds that kids these days consistently prefer their textbooks in print rather than pixels. Whatever the answer, it’s not just about habit.

Another explanation, expressed in a recent Washington Post article on the decline of deep reading, blames a sweeping change in our lifestyles: We’re all so multitasked and attention-fragmented that our brains are losing the ability to focus on long, linear texts. I certainly feel this way, but if I don’t read deeply as often or easily as I used to, it does still happen. It just doesn’t happen on screen, and not even on devices designed specifically for that experience.

Maybe it’s time to start thinking of paper and screens another way: not as an old technology and its inevitable replacement, but as different and complementary interfaces, each stimulating particular modes of thinking. Maybe paper is a technology uniquely suited for imbibing novels and essays and complex narratives, just as screens are for browsing and scanning.

“Reading is human-technology interaction,” says literacy professor Anne Mangen of Norway’s University of Stavenger. “Perhaps the tactility and physical permanence of paper yields a different cognitive and emotional experience.” This is especially true, she says, for “reading that can’t be done in snippets, scanning here and there, but requires sustained attention.”

Mangen is among a small group of researchers who study how people read on different media. It’s a field that goes back several decades, but yields no easy conclusions. People tended to read slowly and somewhat inaccurately on early screens. The technology, particularly e-paper, has improved dramatically, to the point where speed and accuracy aren’t now problems, but deeper issues of memory and comprehension are not yet well-characterized.

Complicating the scientific story further, there are many types of reading. Most experiments involve short passages read by students in an academic setting, and for this sort of reading, some studies have found no obvious differences between screens and paper. Those don’t necessarily capture the dynamics of deep reading, though, and nobody’s yet run the sort of experiment, involving thousands of readers in real-world conditions who are tracked for years on a battery of cognitive and psychological measures, that might fully illuminate the matter.

In the meantime, other research does suggest possible differences. A 2004 study found that students more fully remembered what they’d read on paper. Those results were echoed by an experiment that looked specifically at e-books, and another by psychologist Erik Wästlund at Sweden’s Karlstad University, who found that students learned better when reading from paper.

Wästlund followed up that study with one designed to investigate screen reading dynamics in more detail. He presented students with a variety of on-screen document formats. The most influential factor, he found, was whether they could see pages in their entirety. When they had to scroll, their performance suffered.

According to Wästlund, scrolling had two impacts, the most basic being distraction. Even the slight effort required to drag a mouse or swipe a finger requires a small but significant investment of attention, one that’s higher than flipping a page. Text flowing up and down a page also disrupts a reader’s visual attention, forcing eyes to search for a new starting point and re-focus.

Mangen is among a small group of researchers who study how people read on different media. It’s a field that goes back several decades, but yields no easy conclusions. People tended to read slowly and somewhat inaccurately on early screens. The technology, particularly e-paper, has improved dramatically, to the point where speed and accuracy aren’t now problems, but deeper issues of memory and comprehension are not yet well-characterized.

Complicating the scientific story further, there are many types of reading. Most experiments involve short passages read by students in an academic setting, and for this sort of reading, some studies have found no obvious differences between screens and paper. Those don’t necessarily capture the dynamics of deep reading, though, and nobody’s yet run the sort of experiment, involving thousands of readers in real-world conditions who are tracked for years on a battery of cognitive and psychological measures, that might fully illuminate the matter.

In the meantime, other research does suggest possible differences. A 2004 study found that students more fully remembered what they’d read on paper. Those results were echoed by an experiment that looked specifically at e-books, and another by psychologist Erik Wästlund at Sweden’s Karlstad University, who found that students learned better when reading from paper.

Wästlund followed up that study with one designed to investigate screen reading dynamics in more detail. He presented students with a variety of on-screen document formats. The most influential factor, he found, was whether they could see pages in their entirety. When they had to scroll, their performance suffered.

According to Wästlund, scrolling had two impacts, the most basic being distraction. Even the slight effort required to drag a mouse or swipe a finger requires a small but significant investment of attention, one that’s higher than flipping a page. Text flowing up and down a page also disrupts a reader’s visual attention, forcing eyes to search for a new starting point and re-focus.

Read the entire electronic article here.

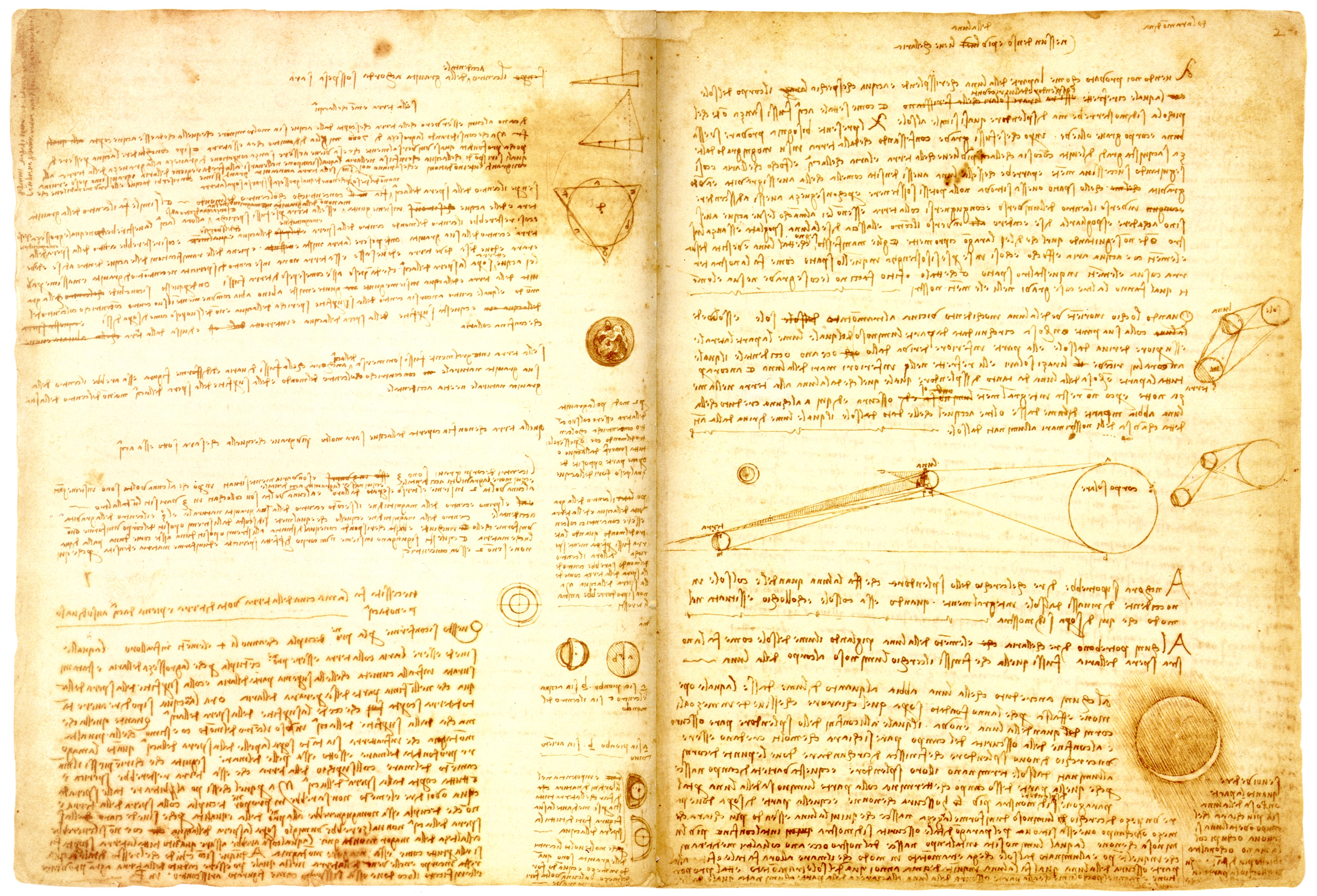

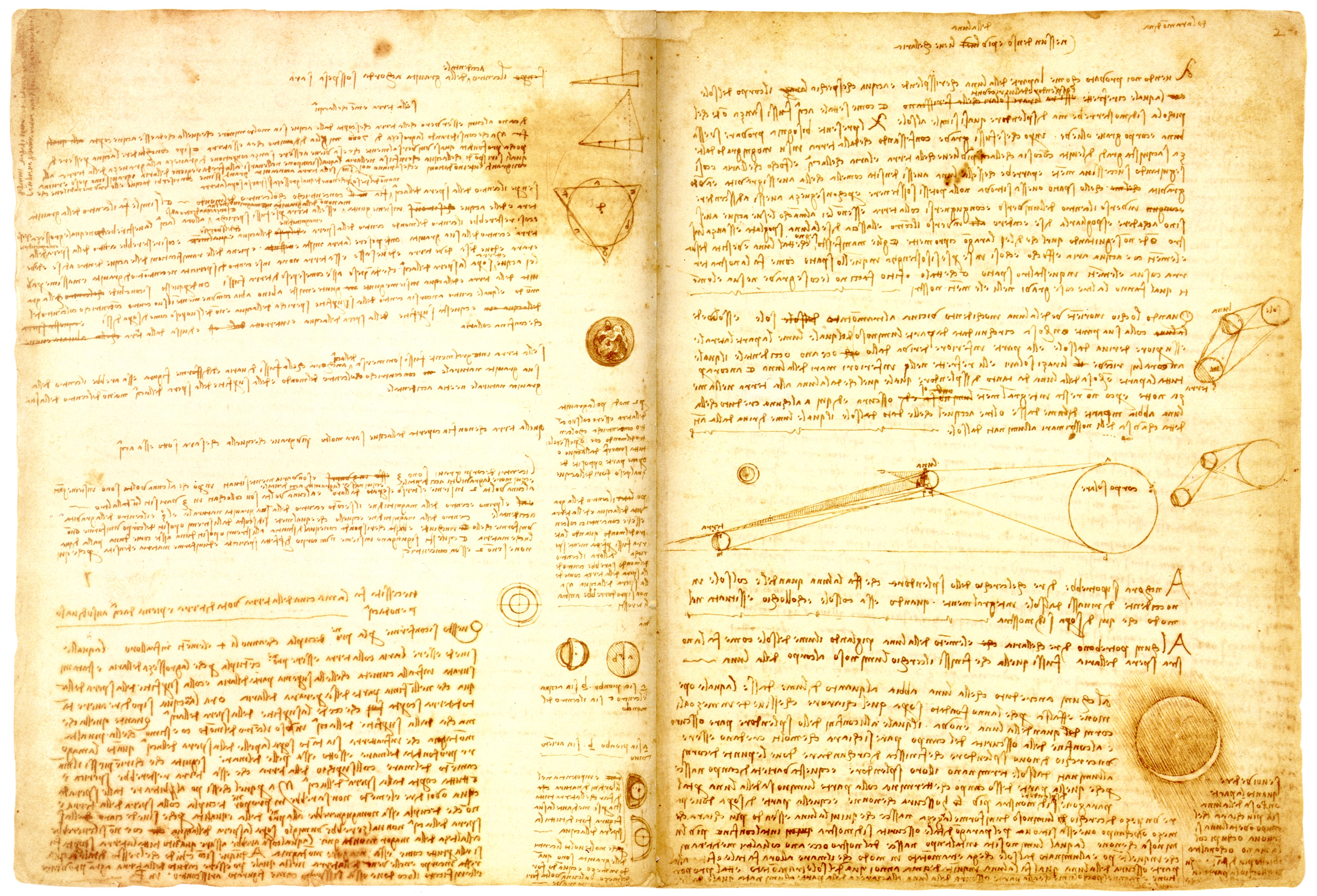

Image: Leicester or Hammer Codex, by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). Courtesy of Wikipedia / Public domain.

Jonathan Jackson has a very rare form of a rare neurological condition. He has synesthesia, which is a cross-connection of two (or more) unrelated senses where an perception in one sense causes an automatic experience in another sense. Some synesthetes, for instance, see various sounds or musical notes as distinct colors (chromesthesia), others perceive different words as distinct tastes (lexical-gustatory synesthesia).

Jonathan Jackson has a very rare form of a rare neurological condition. He has synesthesia, which is a cross-connection of two (or more) unrelated senses where an perception in one sense causes an automatic experience in another sense. Some synesthetes, for instance, see various sounds or musical notes as distinct colors (chromesthesia), others perceive different words as distinct tastes (lexical-gustatory synesthesia).

Yet another research study of gender differences shows some fascinating variation in the way men and women see and process their perceptions of others. Men tend to be perceived as a whole, women, on the other hand, are more likely to be perceived as parts.

Yet another research study of gender differences shows some fascinating variation in the way men and women see and process their perceptions of others. Men tend to be perceived as a whole, women, on the other hand, are more likely to be perceived as parts. Many people in industrialized countries often describe time as flowing like a river: it flows back into the past, and it flows forward into the future. Of course, for bored workers time sometimes stands still, while for kids on summer vacation time flows all too quickly. And, for many people over, say the age of forty, days often drag, but the years fly by.

Many people in industrialized countries often describe time as flowing like a river: it flows back into the past, and it flows forward into the future. Of course, for bored workers time sometimes stands still, while for kids on summer vacation time flows all too quickly. And, for many people over, say the age of forty, days often drag, but the years fly by.

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div] A thoughtful question posed below by philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel over at The Splinted Mind. Gazing in a mirror or reflection is something we all do on a frequent basis. In fact, is there any human activity that trumps this in frequency? Yet, have we ever given thought to how and why we perceive ourselves in space differently to say a car in a rearview mirror. The car in the rearview mirror is quite clearly approaching us from behind as we drive. However, where exactly is our reflection we when cast our eyes at the mirror in the bathrooom?

A thoughtful question posed below by philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel over at The Splinted Mind. Gazing in a mirror or reflection is something we all do on a frequent basis. In fact, is there any human activity that trumps this in frequency? Yet, have we ever given thought to how and why we perceive ourselves in space differently to say a car in a rearview mirror. The car in the rearview mirror is quite clearly approaching us from behind as we drive. However, where exactly is our reflection we when cast our eyes at the mirror in the bathrooom? [div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Scientific American:[end-div]