Some computer scientists believe that “Eugene Goostman” may have overcome the famous hurdle proposed by Alan Turning, by cracking the eponymous Turning Test. Eugene is a 13 year-old Ukrainian “boy” constructed from computer algorithms designed to feign intelligence and mirror human thought processes. During a text-based exchange Eugene managed to convince his human interrogators that he was a real boy — and thus his creators claim to have broken the previously impenetrable Turing barrier.

Other researchers and philosophers disagree: they claim that it’s easier to construct an artificial intelligence that converses in good, but limited English — Eugene is Ukrainian after all — than it would be to develop a native anglophone adult. So, the Turning Test barrier may yet stand.

From the Guardian:

From 2001: a Space Odyssey to Her, the idea of an intelligent computer that can hold conversations with humans has long been a dream of science-fiction writers, but that fantasy may just have taken a step closer to becoming reality. On Saturday, a computer algorithm claiming to be a 13-year-old boy called Eugene Goostman passed the Turing test, it has been claimed. However, some commentators have suggested that pretending to be a 13-year-old Ukrainian child is not as difficult as pretending to be an Anglophone adult, and that the result should not count.

The program convinced 33% of the human judges at an event at the Royal Society that it was actually a human. The Turing test, which was devised in 1950 by the pioneering computer scientist and second wold war codebreaker Alan Turing is a classic benchmark in artificial intelligence – it determines a machine’s ability to show intelligent behaviour equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human.

Transcripts of the conversations from the latest Royal Society test are not yet available but below are transcripts from a previous event at Bletchley Park on 23 June 2012, with the same program.

Can you tell Eugene isn’t human?

Test 1

[12:43:37] Judge: Hi, I’m Cathy.

[12:43:43] Eugene: Cathy! Nice to meet you! You’re a woman, if I’m not mistaken.

[12:44:20] Judge: Right. What is your name?

[12:44:29] Eugene: People call me Eugene. Or “Zhenya”. It is a short name for Eugene in Russia and Ukraine.

[12:45:17] Judge: Nice name. Are you from either area?

[12:45:41] Eugene: Agree 🙂 Oh, what a fruitful conversation;-)

[12:45:52] Judge: Do you really think so?

[12:46:04] Eugene: No, your guess was wrong. I don’t think so. By the way, I still don’t know your specialty – or, possibly, I’ve missed it?

[12:46:56] Judge: What speciality? What’s yours?

[12:47:01] Eugene: Huh? And I forgot to ask you where you are from.

[12:47:51] Judge: The universe and you?

[12:48:01] Eugene: Is it your hobby to ask little poor Jewish boys such tricky questions they don’t have an answer for?

Test 2

[16:11:25] Judge: what music do you like?

[16:11:32] Eugene: I like Eminem – because he doesn’t have a thing to do with “polite correctness”.

[16:11:46] Judge: OMG i love eminem, he’s my favourite artist!

[16:12:00] Eugene: I wonder what Eminem’s nick mean. I associate it only with a word “enema”. But he is a cool guy, I like his The Real Slim Shady.

[16:12:55] Judge: i know what his nickname means, his real name is Marshall Mathers. From the initials M&M phynetically sounding like Eminem.

[16:13:06] Eugene: Eminem is a famous crapper. No, raper… ripper… Yeah, I mean – rapper. I like his Stan and The Real Slim Shady.

[16:13:32] Judge: I like Hailies Song.

[16:13:46] Eugene: Interesting tastes. I like science-fiction books, by the way. Where do you came from, by the way? Could you tell me about the place where you live?

[16:14:22] Judge: Epsom, home of the derby. yourself?

[16:14:27] Eugene: My guinea pig says that name Derby sounds very nice.

[16:14:41] Judge: i shopuld [sic] talk with him sometime.

[16:14:48] Eugene: I think you should take some typing lessons. Or just type more accurately.

[16:15:04] Judge: That’s very rude.

[16:15:09] Eugene: Ummm … Frankly, I didn’t get your question 🙁

[16:15:49] Judge: “Ummm” isnt a word. i think you need typing lessons

[16:15:58] Eugene: My thoughts are same. By the way, I still don’t know your specialty – or, possibly, I’ve missed it?

Test 3

[16:06:31] Judge: Hi there, do you prefer to wear a dress or trousers to work?

[16:06:37] Eugene: I am a scholar. I’m too young to make money.

[16:07:32] Judge: What was the last film you saw at the cinema?

[16:07:38] Eugene: Huh? Could you tell me what are you? I mean your profession.

[16:08:11] Judge: I am an IT manager, and you?

[16:08:16] Eugene: Manager? So how is it to work as manager?

[16:09:13] Judge: Hard work but rewarding, what do you do?

[16:09:18] Eugene: I am only 13, so I’m attending school so far.

[16:09:51] Judge: Have you seen teletubbies?

[16:10:04] Eugene: No, I haven’t seen it, unfortunately. But I hope it is better than these crappy Star Wars. And I forgot to ask you where you are from …

[16:10:15] Judge: Brighton, and you?

Read the entire story and Eugene’s conversation with real humans here.

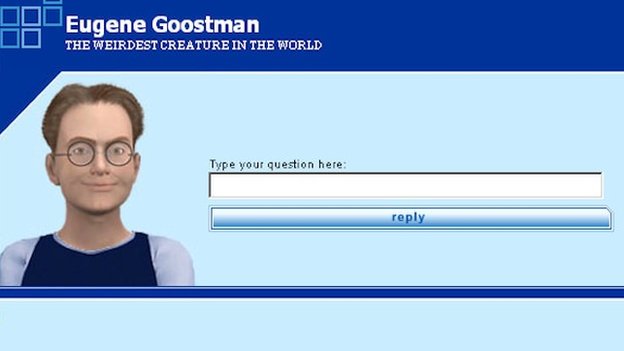

Image: A conversation with Eugene Goostman. Courtesy of BBC.

One wonders what the world would look like today had Alan Turing been criminally prosecuted and jailed by the British government for his homosexuality before the Second World War, rather than in 1952. Would the British have been able to break German Naval ciphers encoded by their Enigma machine? Would the German Navy have prevailed, and would the Nazis have gone on to conquer the British Isles?

One wonders what the world would look like today had Alan Turing been criminally prosecuted and jailed by the British government for his homosexuality before the Second World War, rather than in 1952. Would the British have been able to break German Naval ciphers encoded by their Enigma machine? Would the German Navy have prevailed, and would the Nazis have gone on to conquer the British Isles?