Another day, another heinous, murderous act in the name of religion — the latest this time a French priest killed in his own church by a pair shouting “Allahu akbar!” (To be fair countless other similar acts continue on a daily basis in non-Western nations, but go unreported or under-reported in the mainstream media).

Understandably, local and national religious leaders decry these heinous acts as a evil perversion of Islamic faith. Now, I’d be the first to admit that attributing such horrendous crimes solely to the faiths of the perpetrators is a rather simplistic rationalization. Other factors, such as political disenfranchisement, (perceived) oppression, historical persecution and economic pressures, surely play a triggering and/or catalytic role.

Yet, as Gary Gutting professor of philosophy at the University of Notre Dame reminds us in another of his insightful essays, religious intolerance is a fundamental component. The three main Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — are revelatory faiths. Their teachings are each held to be incontrovertible truth revealed to us by an omniscient God (or a divine messenger). Strict adherence to these beliefs has throughout history led many believers — of all faiths — to enact their intolerance in sometimes very violent ways. Over time, numerous socio-economic pressures have generally softened this intolerance — but not equally across the three faiths.

From NYT:

…

Both Islam and Christianity claim to be revealed religions, holding that their teachings are truths that God himself has conveyed to us and wants everyone to accept. They were, from the start, missionary religions. A religion charged with bringing God’s truth to the world faces the question of how to deal with people who refuse to accept it. To what extent should it tolerate religious error? At certain points in their histories, both Christianity and Islam have been intolerant of other religions, often of each other, even to the point of violence.

This was not inevitable, but neither was it an accident. The potential for intolerance lies in the logic of religions like Christianity and Islam that say their teaching derive from a divine revelation. For them, the truth that God has revealed is the most important truth there is; therefore, denying or doubting this truth is extremely dangerous, both for nonbelievers, who lack this essential truth, and for believers, who may well be misled by the denials and doubts of nonbelievers. Given these assumptions, it’s easy to conclude that even extreme steps are warranted to eliminate nonbelief.

You may object that moral considerations should limit our opposition to nonbelief. Don’t people have a human right to follow their conscience and worship as they think they should? Here we reach a crux for those who adhere to a revealed religion. They can either accept ordinary human standards of morality as a limit on how they interpret divine teachings, or they can insist on total fidelity to what they see as God’s revelation, even when it contradicts ordinary human standards. Those who follow the second view insist that divine truth utterly exceeds human understanding, which is in no position to judge it. God reveals things to us precisely because they are truths we would never arrive at by our natural lights. When the omniscient God has spoken, we can only obey.

For those holding this view, no secular considerations, not even appeals to conventional morality or to practical common sense, can overturn a religious conviction that false beliefs are intolerable. Christianity itself has a long history of such intolerance, including persecution of Jews, crusades against Muslims, and the Thirty Years’ War, in which religious and nationalist rivalries combined to devastate Central Europe. This devastation initiated a move toward tolerance among nations that came to see the folly of trying to impose their religions on foreigners. But intolerance of internal dissidents — Catholics, Jews, rival Protestant sects — continued even into the 19th century. (It’s worth noting that in this period the Muslim Ottoman Empire was in many ways more tolerant than most Christian countries.) But Christians eventually embraced tolerance through a long and complex historical process.

Critiques of Christian revelation by Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire, Rousseau and Hume raised serious questions that made non-Christian religions — and eventually even rejections of religion — intellectually respectable. Social and economic changes — including capitalist economies, technological innovations, and democratic political movements — undermined the social structures that had sustained traditional religion.

The eventual result was a widespread attitude of religious toleration in Europe and the United States. This attitude represented ethical progress, but it implied that religious truth was not so important that its denial was intolerable. Religious beliefs and practices came to be regarded as only expressions of personal convictions, not to be endorsed or enforced by state authority. This in effect subordinated the value of religious faith to the value of peace in a secular society. Today, almost all Christians are reconciled to this revision, and many would even claim that it better reflects the true meaning of their religion.

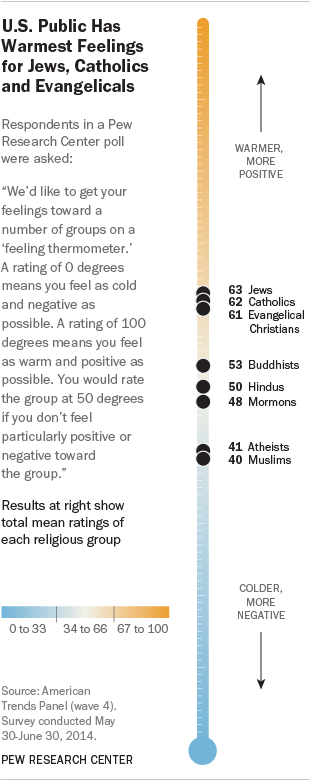

The same is not true of Muslims. A minority of Muslim nations have a high level of religious toleration; for example Albania, Kosovo, Senegal and Sierra Leone. But a majority — including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Iraq and Malaysia — maintain strong restrictions on non-Muslim (and in some cases certain “heretical” Muslim) beliefs and practices. Although many Muslims think God’s will requires tolerance of false religious views, many do not.

Read the entire story here.

Image: D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) movie poster. Courtesy: Sailko / Dekkappai at Wikipedia. Public Domain.

So, you think an all-seeing, all-knowing supreme deity encourages moral behavior and discourages crime? Think again.

So, you think an all-seeing, all-knowing supreme deity encourages moral behavior and discourages crime? Think again.