Many technology companies have separate research teams, or even divisions, that play with new product ideas and invent new gizmos. The conventional wisdom suggests that businesses like Microsoft or IBM need to keep their innovative, far-sighted people away from those tasked with keeping yesterday’s products functioning and today’s customers happy. Google and a handful of other innovators on the other hand follow a different mantra; they invent in hallways and cubes — everywhere.

From Technology Review:

Research vice presidents at some computing giants, such as Microsoft and IBM, rule over divisions housed in dedicated facilities carefully insulated from the rat race of the main businesses. In contrast, Google’s research boss, Alfred Spector, has a small core team and no department or building to call his own. He spends most of his time roaming the open plan, novelty strewn offices of Google’s product divisions, where the vast majority of its fundamental research takes place.

Groups working on Android or data centers are tasked with pushing the boundaries of computer science while simultaneously running Google’s day-to-day business operations.

“There doesn’t need to be a protective shell around our researchers where they think great thoughts,” says Spector. “It’s a collaborative activity across the organization; talent is distributed everywhere.” He says this approach allows Google make fundamental advances quickly—since its researchers are close to piles of data and opportunities to experiment—and then rapidly turn those advances into products.

In 2012, for example, Google’s mobile products saw a 25 percent drop in speech recognition errors after the company pioneered the use of very large neural networks—aka deep learning (see “Google Puts Its Virtual Brain Technology to Work”).

Research vice presidents at some computing giants, such as Microsoft and IBM, rule over divisions housed in dedicated facilities carefully insulated from the rat race of the main businesses. In contrast, Google’s research boss, Alfred Spector, has a small core team and no department or building to call his own. He spends most of his time roaming the open plan, novelty strewn offices of Google’s product divisions, where the vast majority of its fundamental research takes place.

Groups working on Android or data centers are tasked with pushing the boundaries of computer science while simultaneously running Google’s day-to-day business operations.“There doesn’t need to be a protective shell around our researchers where they think great thoughts,” says Spector. “It’s a collaborative activity across the organization; talent is distributed everywhere.” He says this approach allows Google make fundamental advances quickly—since its researchers are close to piles of data and opportunities to experiment—and then rapidly turn those advances into products.

In 2012, for example, Google’s mobile products saw a 25 percent drop in speech recognition errors after the company pioneered the use of very large neural networks—aka deep learning (see “Google Puts Its Virtual Brain Technology to Work”).

Alan MacCormack, an adjunct professor at Harvard Business School who studies innovation and product development in the technology sector, says Google’s approach to research helps it deal with a conundrum facing many large companies. “Many firms are trying to balance a corporate strategy that defines who they are in five years with trying to discover new stuff that is unpredictable—this model has allowed them to do both.” Embedding people working on fundamental research into the core business also makes it possible for Google to encourage creative contributions from workers who would typically be far removed from any kind of research and development, adds MacCormack.

Spector even claims that his company’s secretive Google X division, home of Google Glass and the company’s self-driving car project (see “Glass, Darkly” and “Google’s Robot Cars Are Safer Drivers Than You or I”), is a product development shop rather than a research lab, saying that every project there is focused on a marketable end result. “They have pursued an approach like the rest of Google, a mixture of engineering and research [and] putting these things together into prototypes and products,” he says.

Cynthia Wagner Weick, a management professor at University of the Pacific, thinks that Google’s approach stems from its cofounders’ determination to avoid the usual corporate approach of keeping fundamental research isolated. “They are interested in solving major problems, and not just in the IT and communications space,” she says. Weick recently published a paper singling out Google, Edwards Lifescience, and Elon Musk’s companies, Tesla Motors and Space X, as examples of how tech companies can meet short-term needs while also thinking about far-off ideas.

Google can also draw on academia to boost its fundamental research. It spends millions each year on more than 100 research grants to universities and a few dozen PhD fellowships. At any given time it also hosts around 30 academics who “embed” at the company for up to 18 months. But it has lured many leading computing thinkers away from academia in recent years, particularly in artificial intelligence (see “Is Google Cornering the Market on Deep Learning?”). Those that make the switch get to keep publishing academic research while also gaining access to resources, tools and data unavailable inside universities.

Spector argues that it’s increasingly difficult for academic thinkers to independently advance a field like computer science without the involvement of corporations. Access to piles of data and working systems like those of Google is now a requirement to develop and test ideas that can move the discipline forward, he says. “Google’s played a larger role than almost any company in bringing that empiricism into the mainstream of the field,” he says. “Because of machine learning and operation at scale you can do things that are vastly different. You don’t want to separate researchers from data.”

It’s hard to say how long Google will be able to count on luring leading researchers, given the flush times for competing Silicon Valley startups. “We’re back to a time when there are a lot of startups out there exploring new ground,” says MacCormack, and if competitors can amass more interesting data, they may be able to leach away Google’s research mojo.

Read the entire story here.

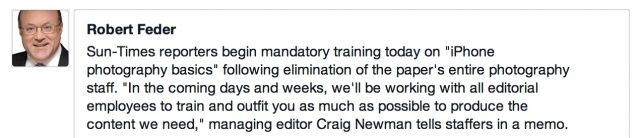

Really, it was only a matter of time. First, digital cameras killed off their film-dependent predecessors and then dealt a death knell for Kodak. Now social media and the #hashtag is doing the same to the professional photographer.

Really, it was only a matter of time. First, digital cameras killed off their film-dependent predecessors and then dealt a death knell for Kodak. Now social media and the #hashtag is doing the same to the professional photographer.

Life coach Jayne Morris suggests that de-cluttering your desk, attic or garage can add positive energy to your personal and business life. Morris has coached numerous business leaders and celebrities in the art of clearing clutter.

Life coach Jayne Morris suggests that de-cluttering your desk, attic or garage can add positive energy to your personal and business life. Morris has coached numerous business leaders and celebrities in the art of clearing clutter.

Starting up a new business was once a demanding and complex process, often undertaken in anonymity in the long shadows between the hours of a regular job. It still is over course. However nowadays “the startup” has become more of an event. The tech sector has raised this to a fine art by spawning an entire self-sustaining and self-promoting industry around startups.

Starting up a new business was once a demanding and complex process, often undertaken in anonymity in the long shadows between the hours of a regular job. It still is over course. However nowadays “the startup” has become more of an event. The tech sector has raised this to a fine art by spawning an entire self-sustaining and self-promoting industry around startups.