Nowhere is the prickly relationship between science and politics more evident than in the climate change debate. The skeptics, many of whom seem to reside right of center in Congress, disbelieve any and all causal links between human activity and global warming. The fossil-fuel burning truckloads of data continue to show upward trends in all measures from mean sea-level and average temperature, to more frequent severe weather and longer droughts. Yet, the self-proclaimed, non-expert policy-makers in Congress continue to disbelieve the science, the data, the analysis and the experts.

But, could the tide be turning? The Republican Chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, Texas Congressman Lamar Smith, wants to see the detail behind the ongoing analysis that shows an ever-warming planet; he’s actually interested in seeing the raw climate data. Joy, at last! Representative Smith has decided to become an expert, right? Wrong. He’s trawling around for evidence that might show tampering of data and biased peer-reviewed analysis — science, after all, is just one great, elitist conspiracy theory.

One has to admire the Congressman’s tenacity. He and his herd of climate-skeptic apologists will continue to fiddle while Rome ignites and burns. But I suppose the warming of our planet is a good thing for Congressman Smith and his disbelieving (in science) followers, for it may well portend the End of Days that they believe (in biblical prophecy) and desire so passionately.

Oh, and the fact that Congressman Lamar Smith is Chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology?! Well, that will have to remain the subject of another post. What next, Donald Trump as head of the ACLU?

From ars technica:

In his position as Chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, Texas Congressman Lamar Smith has spent much of the last few years pressuring the National Science Foundation to ensure that it only funds science he thinks is worthwhile and “in the national interest.” His views on what’s in the national interest may not include the earth sciences, as Smith rejects the conclusions of climate science—as we saw first hand when we saw him speak at the Heartland Institute’s climate “skeptic” conference earlier this year.

So when National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists published an update to the agency’s global surface temperature dataset that slightly increased the short-term warming trend since 1998, Rep. Smith was suspicious. The armada of contrarian blog posts that quickly alleged fraud may have stoked these suspicions. But since, again, he’s the chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, Rep. Smith was able to take action. He’s sent a series of requests to NOAA, which Ars obtained from Committee staff.

The requests started on July 14 when Smith wrote to the NOAA about the paper published in Science by Thomas Karl and his NOAA colleagues. The letter read, in part, “When corrections to scientific data are made, the quality of the analysis and decision-making is brought into question. The conclusions brought forth in this new study have lasting impacts and provide the basis for further action through regulations. With such broad implications, it is imperative that the underlying data and the analysis are made publicly available to ensure that the conclusions found and methods used are of the highest quality.”

Rep. Smith requested that the NOAA provide his office with “[a]ll data related to this study and the updated global datasets” along with the details of the analysis and “all documents and communications” related to part of that analysis.

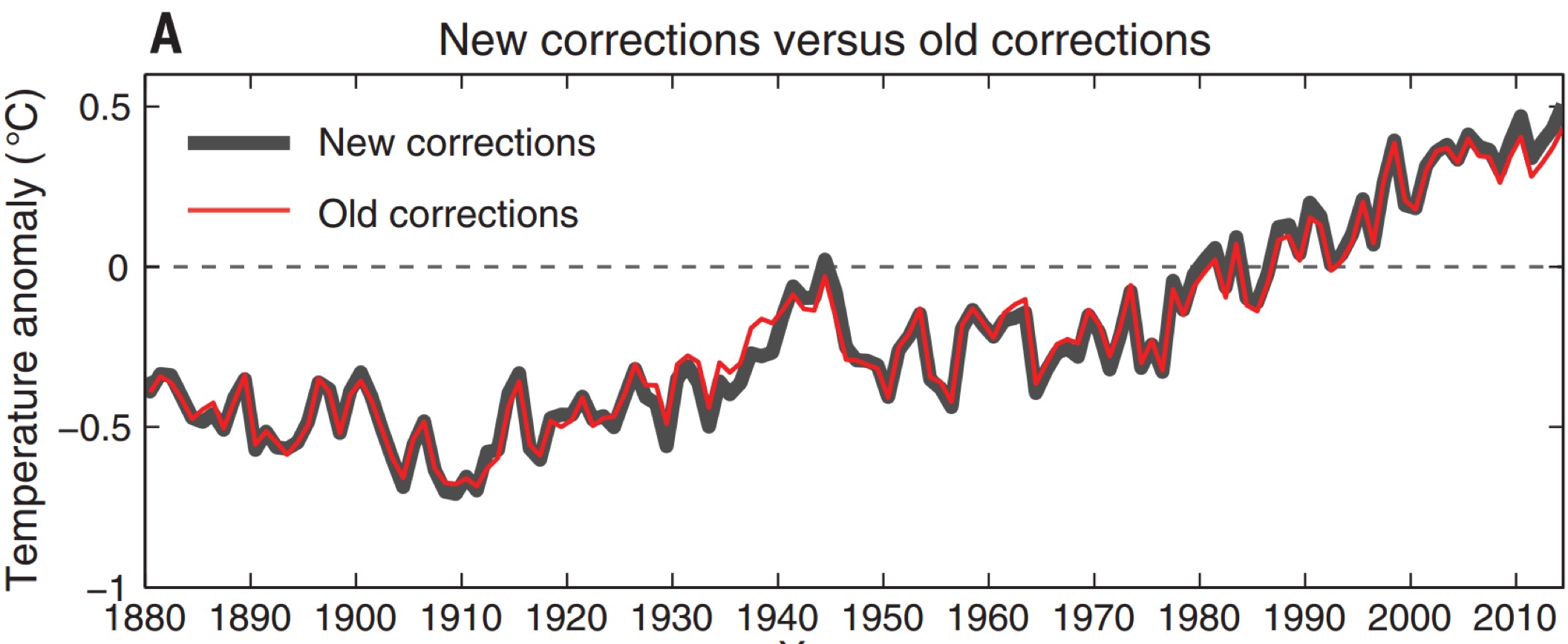

In the publication at issue, the NOAA researchers had pulled in a new, larger database of weather station measurements and updated to the latest version of an ocean surface measurement dataset. The ocean data had new corrections for the different methods ships have used over the years to make temperature measurements. Most significantly, they estimated the difference between modern buoy stations and older thermometer-in-a-bucket measurements.

All the major temperature datasets go through revisions like these, as researchers are able to pull in more data and standardize disparate methods more effectively. Since the NOAA’s update, for example, NASA has pulled the same ocean temperature database into its dataset and updated its weather station database. The changes are always quite small, but they can sometimes alter estimates of some very short-term trends.

The NOAA responded to Rep. Smith’s request by pointing him to the relevant data and methods, all of which had already been publicly available. But on September 10, Smith sent another letter. “After review, I have additional questions related to the datasets used to adjust historical temperature records, as well as NOAA’s practices surrounding its use of climate data,” he wrote. The available data wasn’t enough, and he requested various subsets of the data—buoy readings separated out, for example, with both the raw and corrected data provided.

Read the entire story here.

Image: NOAA temperature record. Courtesy of NOAA.