The Cold War between the former U.S.S.R and the United States brought us the perfect acronym for the ultimate human “game” of brinkmanship — it was called MAD, for mutually assured destruction.

The Cold War between the former U.S.S.R and the United States brought us the perfect acronym for the ultimate human “game” of brinkmanship — it was called MAD, for mutually assured destruction.

Now, thanks to ever-evolving technology, increasing military capability, growing environmental exploitation and unceasing human stupidity we have reached an era that we have dubbed SAD, for self-assured destruction. During the MAD period — the thinking was that it would take the combined efforts of the world’s two superpowers to wreak global catastrophe. Now, as a sign of our so-called progress — in the era of SAD — it only takes one major nation to ensure the destruction of the planet. Few would call this progress. Noam Chomsky offers some choice words on our continuing folly.

From TomDispatch:

What is the future likely to bring? A reasonable stance might be to try to look at the human species from the outside. So imagine that you’re an extraterrestrial observer who is trying to figure out what’s happening here or, for that matter, imagine you’re an historian 100 years from now – assuming there are any historians 100 years from now, which is not obvious – and you’re looking back at what’s happening today. You’d see something quite remarkable.

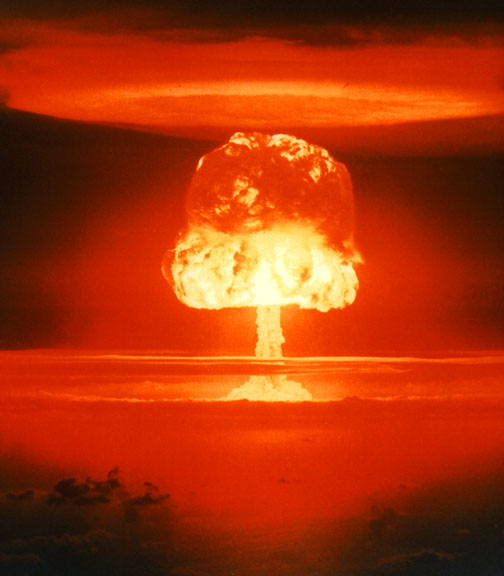

For the first time in the history of the human species, we have clearly developed the capacity to destroy ourselves. That’s been true since 1945. It’s now being finally recognized that there are more long-term processes like environmental destruction leading in the same direction, maybe not to total destruction, but at least to the destruction of the capacity for a decent existence.

And there are other dangers like pandemics, which have to do with globalization and interaction. So there are processes underway and institutions right in place, like nuclear weapons systems, which could lead to a serious blow to, or maybe the termination of, an organized existence.

The question is: What are people doing about it? None of this is a secret. It’s all perfectly open. In fact, you have to make an effort not to see it.

There have been a range of reactions. There are those who are trying hard to do something about these threats, and others who are acting to escalate them. If you look at who they are, this future historian or extraterrestrial observer would see something strange indeed. Trying to mitigate or overcome these threats are the least developed societies, the indigenous populations, or the remnants of them, tribal societies and first nations in Canada. They’re not talking about nuclear war but environmental disaster, and they’re really trying to do something about it.

In fact, all over the world – Australia, India, South America – there are battles going on, sometimes wars. In India, it’s a major war over direct environmental destruction, with tribal societies trying to resist resource extraction operations that are extremely harmful locally, but also in their general consequences. In societies where indigenous populations have an influence, many are taking a strong stand. The strongest of any country with regard to global warming is in Bolivia, which has an indigenous majority and constitutional requirements that protect the “rights of nature.”

Ecuador, which also has a large indigenous population, is the only oil exporter I know of where the government is seeking aid to help keep that oil in the ground, instead of producing and exporting it – and the ground is where it ought to be.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who died recently and was the object of mockery, insult, and hatred throughout the Western world, attended a session of the U.N. General Assembly a few years ago where he elicited all sorts of ridicule for calling George W. Bush a devil. He also gave a speech there that was quite interesting. Of course, Venezuela is a major oil producer. Oil is practically their whole gross domestic product. In that speech, he warned of the dangers of the overuse of fossil fuels and urged producer and consumer countries to get together and try to work out ways to reduce fossil fuel use. That was pretty amazing on the part of an oil producer. You know, he was part Indian, of indigenous background. Unlike the funny things he did, this aspect of his actions at the U.N. was never even reported.

So, at one extreme you have indigenous, tribal societies trying to stem the race to disaster. At the other extreme, the richest, most powerful societies in world history, like the United States and Canada, are racing full-speed ahead to destroy the environment as quickly as possible. Unlike Ecuador, and indigenous societies throughout the world, they want to extract every drop of hydrocarbons from the ground with all possible speed.

Both political parties, President Obama, the media, and the international press seem to be looking forward with great enthusiasm to what they call “a century of energy independence” for the United States. Energy independence is an almost meaningless concept, but put that aside. What they mean is: we’ll have a century in which to maximize the use of fossil fuels and contribute to destroying the world.

And that’s pretty much the case everywhere. Admittedly, when it comes to alternative energy development, Europe is doing something. Meanwhile, the United States, the richest and most powerful country in world history, is the only nation among perhaps 100 relevant ones that doesn’t have a national policy for restricting the use of fossil fuels, that doesn’t even have renewable energy targets. It’s not because the population doesn’t want it. Americans are pretty close to the international norm in their concern about global warming. It’s institutional structures that block change. Business interests don’t want it and they’re overwhelmingly powerful in determining policy, so you get a big gap between opinion and policy on lots of issues, including this one.

So that’s what the future historian – if there is one – would see. He might also read today’s scientific journals. Just about every one you open has a more dire prediction than the last.

The other issue is nuclear war. It’s been known for a long time that if there were to be a first strike by a major power, even with no retaliation, it would probably destroy civilization just because of the nuclear-winter consequences that would follow. You can read about it in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. It’s well understood. So the danger has always been a lot worse than we thought it was.

We’ve just passed the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which was called “the most dangerous moment in history” by historian Arthur Schlesinger, President John F. Kennedy’s advisor. Which it was. It was a very close call, and not the only time either. In some ways, however, the worst aspect of these grim events is that the lessons haven’t been learned.

What happened in the missile crisis in October 1962 has been prettified to make it look as if acts of courage and thoughtfulness abounded. The truth is that the whole episode was almost insane. There was a point, as the missile crisis was reaching its peak, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev wrote to Kennedy offering to settle it by a public announcement of a withdrawal of Russian missiles from Cuba and U.S. missiles from Turkey. Actually, Kennedy hadn’t even known that the U.S. had missiles in Turkey at the time. They were being withdrawn anyway, because they were being replaced by more lethal Polaris nuclear submarines, which were invulnerable.

So that was the offer. Kennedy and his advisors considered it – and rejected it. At the time, Kennedy himself was estimating the likelihood of nuclear war at a third to a half. So Kennedy was willing to accept a very high risk of massive destruction in order to establish the principle that we – and only we – have the right to offensive missiles beyond our borders, in fact anywhere we like, no matter what the risk to others – and to ourselves, if matters fall out of control. We have that right, but no one else does.

Kennedy did, however, accept a secret agreement to withdraw the missiles the U.S. was already withdrawing, as long as it was never made public. Khrushchev, in other words, had to openly withdraw the Russian missiles while the US secretly withdrew its obsolete ones; that is, Khrushchev had to be humiliated and Kennedy had to maintain his macho image. He’s greatly praised for this: courage and coolness under threat, and so on. The horror of his decisions is not even mentioned – try to find it on the record.

And to add a little more, a couple of months before the crisis blew up the United States had sent missiles with nuclear warheads to Okinawa. These were aimed at China during a period of great regional tension.

Well, who cares? We have the right to do anything we want anywhere in the world. That was one grim lesson from that era, but there were others to come.

Ten years after that, in 1973, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called a high-level nuclear alert. It was his way of warning the Russians not to interfere in the ongoing Israel-Arab war and, in particular, not to interfere after he had informed the Israelis that they could violate a ceasefire the U.S. and Russia had just agreed upon. Fortunately, nothing happened.

Ten years later, President Ronald Reagan was in office. Soon after he entered the White House, he and his advisors had the Air Force start penetrating Russian air space to try to elicit information about Russian warning systems, Operation Able Archer. Essentially, these were mock attacks. The Russians were uncertain, some high-level officials fearing that this was a step towards a real first strike. Fortunately, they didn’t react, though it was a close call. And it goes on like that.

At the moment, the nuclear issue is regularly on front pages in the cases of North Korea and Iran. There are ways to deal with these ongoing crises. Maybe they wouldn’t work, but at least you could try. They are, however, not even being considered, not even reported.

Read the entire article here.

Image: President Kennedy signs Cuba quarantine proclamation, 23 October 1962. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Cold War between the former U.S.S.R and the United States brought us the perfect acronym for the ultimate human “game” of brinkmanship — it was called MAD, for mutually assured destruction.

The Cold War between the former U.S.S.R and the United States brought us the perfect acronym for the ultimate human “game” of brinkmanship — it was called MAD, for mutually assured destruction.

theDiagonal usually does not report on the news. Though we do make a few worthy exceptions based on the import or surreal nature of the event. A case in point below.

theDiagonal usually does not report on the news. Though we do make a few worthy exceptions based on the import or surreal nature of the event. A case in point below.