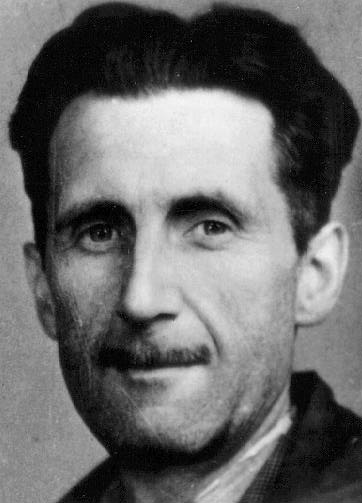

Next time you browse through your company’s compensation or business expense policies, or for that matter, anything written by the human resources (HR) department, cast your mind to George Orwell. In one of his critical essays Politics and the English Language, Orwell makes a clear case for the connection between linguistic obfuscation and political power. While Orwell’s obsession was on the political machine, you could just as well apply his reasoning to the mangled literary machinations of every corporate HR department.

Oh, the pen is indeed mightier than the sword, especially when it is used to construct obtuse passive sentences without a subject — perfect for a rulebook that all citizens must follow and that no one can challenge.

From the Guardian:

In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of human resources’. All issues are human resource issues, and human resources itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.

OK, that’s not exactly what Orwell wrote. The hair-splitters among you will moan that I’ve taken the word “politics” out of the above and replaced it with “human resources”. Sorry.

But I think there’s no denying that had he been alive today, Orwell – the great opponent and satirist of totalitarianism – would have deplored the bureaucratic repression of HR. He would have hated their blind loyalty to power, their unquestioning faithfulness to process, their abhorrence of anything or anyone deviating from the mean.

In particular, Orwell would have utterly despised the language that HR people use. In his excellent essay Politics and the English Language (where he began the thought that ended with Newspeak), Orwell railed against the language crimes committed by politicians.

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible … Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements.

Repeat the politics/human resources switch in the above and the argument remains broadly the same. Yes, HR is not explaining away murders, but it nonetheless deliberately misuse language as a sort of low-tech mind control to avert our eyes from office atrocities and keep us fixed on our inboxes. Thus mass sackings are wrapped up in cowardly sophistry and called rightsizings, individuals are offboarded to the jobcentre and the few hardy souls left are consoled by their membership of a more streamlined organisation.

Orwell would have despised the passive constructions that are the HR department’s default setting. Want some flexibility in your contract? HR says company policy is unable to support that. Forgotten to accede to some arbitrary and impractical office rule? HR says we are minded to ask everyone to remember that it is essential to comply by rule X. Try to question whether an ill-judged commitment could be reversed? HR apologises meekly that the decision has been made.

Not giving subjects to any of these responses is a deliberate ploy. Subjects give ownership. They imbue accountability. Not giving sentences subjects means that HR is passing the buck, but to no one in particular. And with no subject, no one can be blamed, or protested against.

The passive construction is also designed to give the sense that it’s not HR speaking, but that they are the conduit for a higher-up and incontestable power. It’s designed to be both authoritative and banal, so that we torpidly accept it, like the sovereignty of the Queen. It’s saying: “This is the way things are – deal with it because it isn’t changing.” It’s indifferent and deliberately opaque. It’s the worst kind of utopianism (the kind David Graeber targets in his recent book on “stupidity and the secret joys of bureaucracy”), where system and rule are king and hang the individual. It’s deeply, deeply oppressive.

Annual leave is perhaps an even worse example of HR’s linguistic malpractice. The phrase gives the sense that we are not sitting in the office but rather fighting some dismal war and that we should be grateful for the mercy of Field Marshal HR in allowing us a finite absence from the front line. Is it too indulgent and too frivolous to say that we are going on holiday (even if we’re just taking the day to go to Ikea)? Would it so damage our career prospects? Would the emerging markets of the world be emboldened by the decadence and complacency of saying we’re going on hols? I don’t think so, but they clearly do.

Actually, I don’t think it’s so much of a stretch to imagine Orwell himself establishing the whole HR enterprise as a sort of grim parody of Stalinism; a never-ending, ever-expanding live action art installation sequel to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Look at your office’s internal newsletter. Is it an incomprehensible black hole of sense? Is it trying to prod you into a place of content, incognisant of all the everyday hardships and irritations you endure? If your answer is yes, then I think that like me, you find it fairly easy to imagine Orwell composing these Newspeak emails from beyond the grave to make us believe that War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery and 2+2=5.

Delving deeper, the parallels become increasingly hard to ignore. Company restructures and key performance indicators make no sense in the abstract, merely serving to demotivate the workforce, sap confidence and obstruct productivity. So are they actually cleverly designed parodies of Stalin’s purges and the cult of Stakhanovism?

Read the entire story here.

If you are an English speaker and are over the age of 39 you may be pondering the fate of the English language. As the younger generations fill cyberspace with terabytes of misspelled texts and tweets do you not wonder if gorgeous grammatical language will survive? Are the technophobes and anti-Twitterites doomed to a future world of #hashtag-driven conversation and ADHD-like literature? Those of us who care are reminded of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language”, in which he decried the swelling ugliness of the language at the time.

If you are an English speaker and are over the age of 39 you may be pondering the fate of the English language. As the younger generations fill cyberspace with terabytes of misspelled texts and tweets do you not wonder if gorgeous grammatical language will survive? Are the technophobes and anti-Twitterites doomed to a future world of #hashtag-driven conversation and ADHD-like literature? Those of us who care are reminded of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language”, in which he decried the swelling ugliness of the language at the time.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another.

One great writer reflects on the influences of another. The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.

The whole experience was deeply disturbing, but I am forever grateful to Orwell for alerting me early to the danger flags I’ve tried to watch out for since. As Orwell taught, it isn’t the labels – Christianity, socialism, Islam, democracy, two legs bad, four legs good, the works – that are definitive, but the acts done in their names.