[div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div]

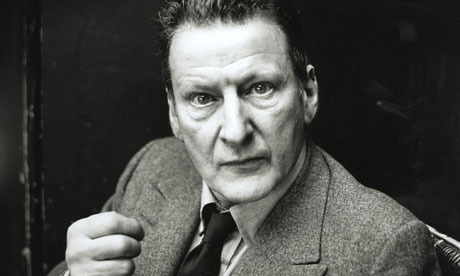

Robert Rauschenberg, the irrepressibly prolific American artist who time and again reshaped art in the 20th century, died on Monday night at his home on Captiva Island, Fla. He was 82.

Robert Rauschenberg, the irrepressibly prolific American artist who time and again reshaped art in the 20th century, died on Monday night at his home on Captiva Island, Fla. He was 82.

The cause was heart failure, said Arne Glimcher, chairman of PaceWildenstein, the Manhattan gallery that represents Mr. Rauschenberg.

Mr. Rauschenberg’s work gave new meaning to sculpture. “Canyon,” for instance, consisted of a stuffed bald eagle attached to a canvas. “Monogram” was a stuffed goat girdled by a tire atop a painted panel. “Bed” entailed a quilt, sheet and pillow, slathered with paint, as if soaked in blood, framed on the wall. All became icons of postwar modernism.

A painter, photographer, printmaker, choreographer, onstage performer, set designer and, in later years, even a composer, Mr. Rauschenberg defied the traditional idea that an artist stick to one medium or style. He pushed, prodded and sometimes reconceived all the mediums in which he worked.

Building on the legacies of Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Schwitters, Joseph Cornell and others, he helped obscure the lines between painting and sculpture, painting and photography, photography and printmaking, sculpture and photography, sculpture and dance, sculpture and technology, technology and performance art — not to mention between art and life.

Mr. Rauschenberg was also instrumental in pushing American art onward from Abstract Expressionism, the dominant movement when he emerged, during the early 1950s. He became a transformative link between artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and those who came next, artists identified with Pop, Conceptualism, Happenings, Process Art and other new kinds of art in which he played a signal role.

No American artist, Jasper Johns once said, invented more than Mr. Rauschenberg. Mr. Johns, John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Mr. Rauschenberg, without sharing exactly the same point of view, collectively defined this new era of experimentation in American culture.

Apropos of Mr. Rauschenberg, Cage once said, “Beauty is now underfoot wherever we take the trouble to look.” Cage meant that people had come to see, through Mr. Rauschenberg’s efforts, not just that anything, including junk on the street, could be the stuff of art (this wasn’t itself new), but that it could be the stuff of an art aspiring to be beautiful — that there was a potential poetics even in consumer glut, which Mr. Rauschenberg celebrated.

“I really feel sorry for people who think things like soap dishes or mirrors or Coke bottles are ugly,” he once said, “because they’re surrounded by things like that all day long, and it must make them miserable.”

The remark reflected the optimism and generosity of spirit that Mr. Rauschenberg became known for. His work was likened to a St. Bernard: uninhibited and mostly good-natured. He could be the same way in person. When he became rich, he gave millions of dollars to charities for women, children, medical research, other artists and Democratic politicians.

A brash, garrulous, hard-drinking, open-faced Southerner, he had a charm and peculiar Delphic felicity with language that masked a complex personality and an equally multilayered emotional approach to art, which evolved as his stature did. Having begun by making quirky, small-scale assemblages out of junk he found on the street in downtown Manhattan, he spent increasing time in his later years, after he had become successful and famous, on vast international, ambassadorial-like projects and collaborations.

Conceived in his immense studio on the island of Captiva, off southwest Florida, these projects were of enormous size and ambition; for many years he worked on one that grew literally to exceed the length of its title, “The 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece.” They generally did not live up to his earlier achievements. Even so, he maintained an equanimity toward the results. Protean productivity went along with risk, he felt, and risk sometimes meant failure.

The process — an improvisatory, counterintuitive way of doing things — was always what mattered most to him. “Screwing things up is a virtue,” he said when he was 74. “Being correct is never the point. I have an almost fanatically correct assistant, and by the time she re-spells my words and corrects my punctuation, I can’t read what I wrote. Being right can stop all the momentum of a very interesting idea.”

This attitude also inclined him, as the painter Jack Tworkov once said, “to see beyond what others have decided should be the limits of art.”

He “keeps asking the question — and it’s a terrific question philosophically, whether or not the results are great art,” Mr. Tworkov said, “and his asking it has influenced a whole generation of artists.”

A Wry, Respectful Departure

That generation was the one that broke from Pollock and company. Mr. Rauschenberg maintained a deep but mischievous respect for Abstract Expressionist heroes like de Kooning and Barnett Newman. Famously, he once painstakingly erased a drawing by de Kooning, an act both of destruction and devotion. Critics regarded the all-black paintings and all-red paintings he made in the early 1950s as spoofs of de Kooning and Pollock. The paintings had roiling, bubbled surfaces made from scraps of newspapers embedded in paint.

But these were just as much homages as they were parodies. De Kooning, himself a parodist, had incorporated bits of newspapers in pictures, and Pollock stuck cigarette butts to canvases.

Mr. Rauschenberg’s “Automobile Tire Print,” from the early 1950s — resulting from Cage’s driving an inked tire of a Model A Ford over 20 sheets of white paper — poked fun at Newman’s famous “zip” paintings.

At the same time, Mr. Rauschenberg was expanding on Newman’s art. The tire print transformed Newman’s zip — an abstract line against a monochrome backdrop with spiritual pretensions — into an artifact of everyday culture, which for Mr. Rauschenberg had its own transcendent dimension.

Mr. Rauschenberg frequently alluded to cars and spaceships, even incorporating real tires and bicycles into his art. This partly reflected his own restless, peripatetic imagination. The idea of movement was logically extended when he took up dance and performance.

There was, beneath this, a darkness to many of his works, notwithstanding their irreverence. “Bed” (1955) was gothic. The all-black paintings were solemn and shuttered. The red paintings looked charred, with strips of fabric akin to bandages, from which paint dripped like blood. “Interview” (1955), which resembled a cabinet or closet with a door, enclosing photos of bullfighters, a pinup, a Michelangelo nude, a fork and a softball, suggested some black-humored encoded erotic message.

There were many other images of downtrodden and lonely people, rapt in thought; pictures of ancient frescoes, out of focus as if half remembered; photographs of forlorn, neglected sites; bits and pieces of faraway places conveying a kind of nostalgia or remoteness. In bringing these things together, the art implied consolation.

Mr. Rauschenberg, who knew that not everybody found it easy to grasp the open-endedness of his work, once described to the writer Calvin Tomkins an encounter with a woman who had reacted skeptically to “Monogram” (1955-59) and “Bed” in his 1963 retrospective at the Jewish Museum, one of the events that secured Mr. Rauschenberg’s reputation: “To her, all my decisions seemed absolutely arbitrary — as though I could just as well have selected anything at all — and therefore there was no meaning, and that made it ugly.

[div class=attrib]More from theSource here.[end-div]

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

In recent years narcissism has been taking a bad rap. So much so that Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) was slated for removal from the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V. The DSM-V is the professional reference guide published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had decided that they needed only 5 fundamental types of personality disorder: anti-social, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal. Hence no need for NPD.

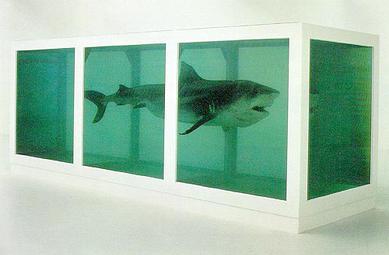

In recent years narcissism has been taking a bad rap. So much so that Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) was slated for removal from the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – DSM-V. The DSM-V is the professional reference guide published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists had decided that they needed only 5 fundamental types of personality disorder: anti-social, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal. Hence no need for NPD. Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years.

Regardless of what you may believe about Damien Hirst or think about his art it would not be stretching the truth to say he single-handedly resurrected the British contemporary art scene over the last 15 years. The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes.

The ubiquity of point-and-click digital cameras and camera-equipped smartphones seems to be leading us towards an era where it is more common to snap and share a picture of the present via a camera lens than it is to experience the present individually and through one’s own eyes.

[div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian:[end-div]

Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

Where evaluating artistic style was once the exclusive domain of seasoned art historians and art critics with many decades of experience, a computer armed with sophisticated image processing software is making a stir in art circles.

A recently opened solo art show takes an fascinating inside peek at the cryonics industry. Entitled “The Prospect of Immortality” the show features photography by Murray Ballard. Ballard’s collection of images follows a 5-year investigation of cryonics in England, the United States and Russia. Cryonics is the practice of freezing the human body just after death in the hope that future science will one day have the capability of restoring it to life.

A recently opened solo art show takes an fascinating inside peek at the cryonics industry. Entitled “The Prospect of Immortality” the show features photography by Murray Ballard. Ballard’s collection of images follows a 5-year investigation of cryonics in England, the United States and Russia. Cryonics is the practice of freezing the human body just after death in the hope that future science will one day have the capability of restoring it to life. A fascinating and disturbing series of still photographs from Andris Feldmanis shows us what the television “sees” as its viewers glare seemingly mindlessly at the box. As Feldmanis describes,

A fascinating and disturbing series of still photographs from Andris Feldmanis shows us what the television “sees” as its viewers glare seemingly mindlessly at the box. As Feldmanis describes, The next time you wander through an art gallery and feel lightheaded after seeing a Monroe silkscreen by Warhol, or feel reflective and soothed by a scene from Monet’s garden you’ll be in good company. New research shows that the body reacts to art not just our grey matter.

The next time you wander through an art gallery and feel lightheaded after seeing a Monroe silkscreen by Warhol, or feel reflective and soothed by a scene from Monet’s garden you’ll be in good company. New research shows that the body reacts to art not just our grey matter. Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox.

Jonathan Jones over at the Guardian puts an creative spin (pun intended) on the latest developments in the world of particle physics. He suggests that we might borrow from the world of modern and contemporary art to help us take the vast imaginative leaps necessary to understand our physical world and its underlying quantum mechanical nature bound up in uncertainty and paradox. [div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From the Guardian:[end-div]

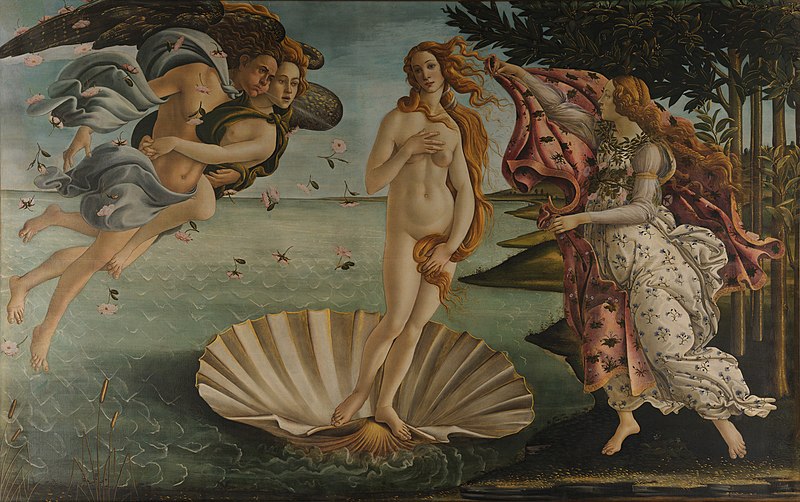

The lengthy corridors of art history over the last five hundred years are decorated with numerous bold and monumental works. Just to name a handful of memorable favorites you’ll see a pattern emerge:

The lengthy corridors of art history over the last five hundred years are decorated with numerous bold and monumental works. Just to name a handful of memorable favorites you’ll see a pattern emerge:  Artist

Artist  The guests were chic, the bordeaux was sipped with elegant restraint and the hostess was suitably glamorous in a canary yellow cocktail dress. To an outside observer who made it past the soirée privée sign on the door of the Anne de Villepoix gallery on Thursday night, it would have seemed the quintessential Parisian art viewing.

The guests were chic, the bordeaux was sipped with elegant restraint and the hostess was suitably glamorous in a canary yellow cocktail dress. To an outside observer who made it past the soirée privée sign on the door of the Anne de Villepoix gallery on Thursday night, it would have seemed the quintessential Parisian art viewing. [div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div]

[div class=attrib]From The New York Times:[end-div] The earthquake in central Italy last week zeroed in on the beautiful medieval hill town of L’Aquila. It claimed the lives of 294 young and old, injured several thousand more, and made tens of thousands homeless. This is a heart-wrenching human tragedy. It’s also a cultural one. The quake razed centuries of L’Aquila’s historical buildings, broke the foundations of many of the town’s churches and public spaces, destroyed countless cultural artifacts, and forever buried much of the town’s irreplaceable art under tons of twisted iron and fractured stone.

The earthquake in central Italy last week zeroed in on the beautiful medieval hill town of L’Aquila. It claimed the lives of 294 young and old, injured several thousand more, and made tens of thousands homeless. This is a heart-wrenching human tragedy. It’s also a cultural one. The quake razed centuries of L’Aquila’s historical buildings, broke the foundations of many of the town’s churches and public spaces, destroyed countless cultural artifacts, and forever buried much of the town’s irreplaceable art under tons of twisted iron and fractured stone.

Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg