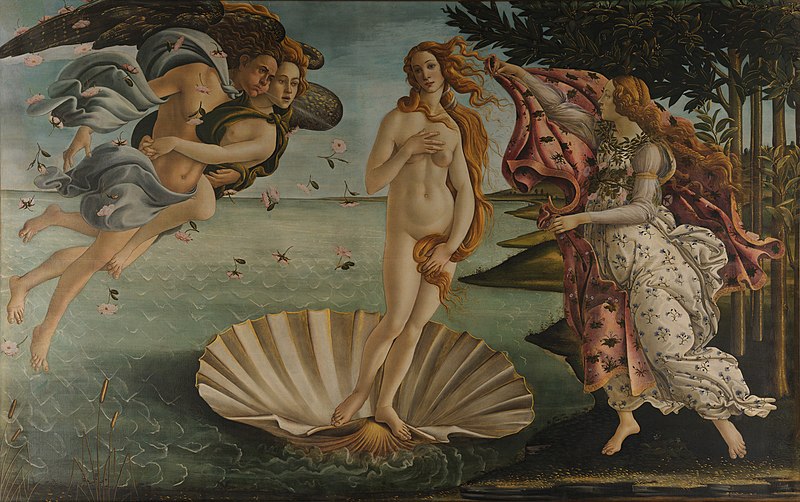

The future of good design may actually lie in intentionally doing the wrong thing. While we are drawn to the beauty of symmetry — in faces, in objects — we are also drawn by the promise of imperfection.

From Wired:

In the late 1870s, Edgar Degas began work on what would become one of his most radical paintings, Jockeys Before the Race. Degas had been schooled in techniques of the neoclassicist and romanticist masters but had begun exploring subject matter beyond the portraits and historical events that were traditionally considered suitable for fine art, training his eye on café culture, common laborers, and—most famously—ballet dancers. But with Jockeys, Degas pushed past mild provocation. He broke some of the most established formulas of composition. The painting is technically exquisite, the horses vividly sculpted with confident brushstrokes, their musculature perfectly rendered. But while composing this beautifully balanced, impressionistically rendered image, Degas added a crucial, jarring element: a pole running vertically—and asymmetrically—in the immediate foreground, right through the head of one of the horses.

Degas wasn’t just “thinking outside of the box,” as the innovation cliché would have it. He wasn’t trying to overturn convention to find a more perfect solution. He was purposely creating something that wasn’t pleasing, intentionally doing the wrong thing. Naturally viewers were horrified. Jockeys was lampooned in the magazine Punch, derided as a “mistaken impression.” But over time, Degas’ transgression provided inspiration for other artists eager to find new ways to inject vitality and dramatic tension into work mired in convention. You can see its influence across art history, from Frederic Remington’s flouting of traditional compositional technique to the crackling photojournalism of Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Degas was engaged in a strategy that has shown up periodically for centuries across every artistic and creative field. Think of it as one step in a cycle: In the early stages, practitioners dedicate themselves to inventing and improving the rules—how to craft the most pleasing chord progression, the perfectly proportioned building, the most precisely rendered amalgamation of rhyme and meter. Over time, those rules become laws, and artists and designers dedicate themselves to excelling within these agreed-upon parameters, creating work of unparalleled refinement and sophistication—the Pantheon, the Sistine Chapel, the Goldberg Variations. But once a certain maturity has been reached, someone comes along who decides to take a different route. Instead of trying to create an ever more polished and perfect artifact, this rebel actively seeks out imperfection—sticking a pole in the middle of his painting, intentionally adding grungy feedback to a guitar solo, deliberately photographing unpleasant subjects. Eventually some of these creative breakthroughs end up becoming the foundation of a new set of aesthetic rules, and the cycle begins again.

DEGAS WASN’T JUST THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX. HE WAS PURPOSELY CREATING SOMETHING THAT WASN’T PLEASING.

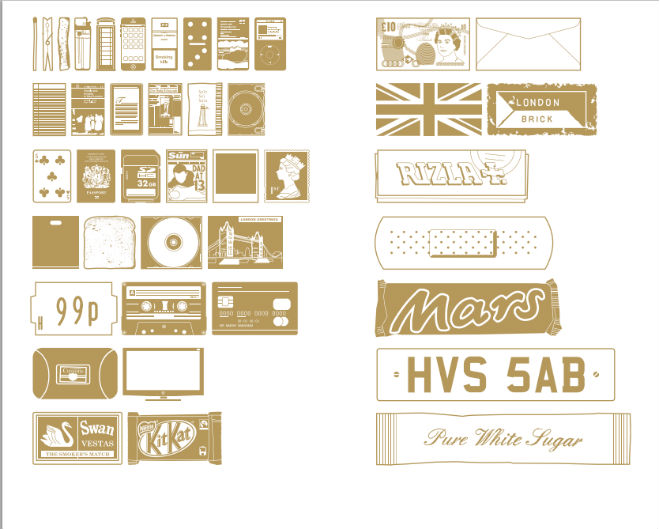

For the past 30 years, the field of technology design has been working its way through the first two stages of this cycle, an industry-wide march toward more seamless experiences, more delightful products, more leverage over the world around us. Look at our computers: beige and boxy desktop machines gave way to bright and colorful iMacs, which gave way to sleek and sexy laptops, which gave way to addictively touchable smartphones. It’s hard not to look back at this timeline and see it as a great story of human progress, a joint effort to experiment and learn and figure out the path toward a more refined and universally pleasing design.

All of this has resulted in a world where beautifully constructed tech is more powerful and more accessible than ever before. It is also more consistent. That’s why all smartphones now look basically the same—gleaming black glass with handsomely cambered edges. Google, Apple, and Microsoft all use clean, sans-serif typefaces in their respective software. After years of experimentation, we have figured out what people like and settled on some rules.

But there’s a downside to all this consensus—it can get boring. From smartphones to operating systems to web page design, it can start to feel like the truly transformational moments have come and gone, replaced by incremental updates that make our devices and interactions faster and better.

This brings us to an important and exciting moment in the design of our technologies. We have figured out the rules of creating sleek sophistication. We know, more or less, how to get it right. Now, we need a shift in perspective that allows us to move forward. We need a pole right through a horse’s head. We need to enter the third stage of this cycle. It’s time to stop figuring out how to do things the right way, and start getting it wrong.

In late 2006, when I was creative director here at WIRED, I was working on the design of a cover featuring John Hodgman. We were far along in the process—Hodgman was styled and photographed, the cover lines written, our fonts selected, the layout firmed up. I had been aiming for a timeless design with a handsome monochromatic color palette, a cover that evoked a 1960s jet-set vibe. When I presented my finished design, WIRED’s editor at the time, Chris Anderson, complained that the cover was too drab. He uttered the prescriptive phrase all graphic designers hate hearing: “Can’t you just add more colors?”

I demurred. I felt the cover was absolutely perfect. But Chris did not, and so, in a spasm of designerly “fuck you,” I drew a small rectangle into my design, a little stripe coming off from the left side of the page, rudely breaking my pristine geometries. As if that weren’t enough, I filled it with the ugliest hue I could find: neon orange— Pantone 811, to be precise. My perfect cover was now ruined!

By the time I came to my senses a couple of weeks later, it was too late. The cover had already been sent to the printer. My anger morphed into regret. To the untrained eye, that little box might not seem so offensive, but I felt that I had betrayed one of the most crucial lessons I learned in design school—that every graphic element should serve a recognizable function. This stray dash of color was careless at best, a postmodernist deviation with no real purpose or value. It confused my colleagues and detracted from the cover’s clarity, unnecessarily making the reader more conscious of the design.

But you know what? I actually came to like that crass little neon orange bar. I ended up including a version of it on the next month’s cover, and again the month after that. It added something, even though I couldn’t explain what it was. I began referring to this idea—intentionally making “bad” design choices—as Wrong Theory, and I started applying it in little ways to all of WIRED’s pages. Pictures that were supposed to run large, I made small. Where type was supposed to run around graphics, I overlapped the two. Headlines are supposed to come at the beginning of stories? I put them at the end. I would even force our designers to ruin each other’s “perfect” layouts.

At the time, this represented a major creative breakthrough for me—the idea that intentional wrongness could yield strangely pleasing results. Of course I was familiar with the idea of rule-breaking innovation—that each generation reacts against the one that came before it, starting revolutions, turning its back on tired conventions. But this was different. I wasn’t just throwing out the rulebook and starting from scratch. I was following the rules, then selectively breaking one or two for maximum impact.

Read the entire article here.

Many mathematicians and those not mathematically oriented would consider Albert Einstein’s equation stating energy=mass equivalence to be singularly simple and beautiful. Indeed, e=mc2 is perhaps one of the few equations to have entered the general public consciousness. However, there are a number of other less well known mathematical constructs that convey this level of significance and fundamental beauty as well. Wired lists several to consider.

Many mathematicians and those not mathematically oriented would consider Albert Einstein’s equation stating energy=mass equivalence to be singularly simple and beautiful. Indeed, e=mc2 is perhaps one of the few equations to have entered the general public consciousness. However, there are a number of other less well known mathematical constructs that convey this level of significance and fundamental beauty as well. Wired lists several to consider. As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”.

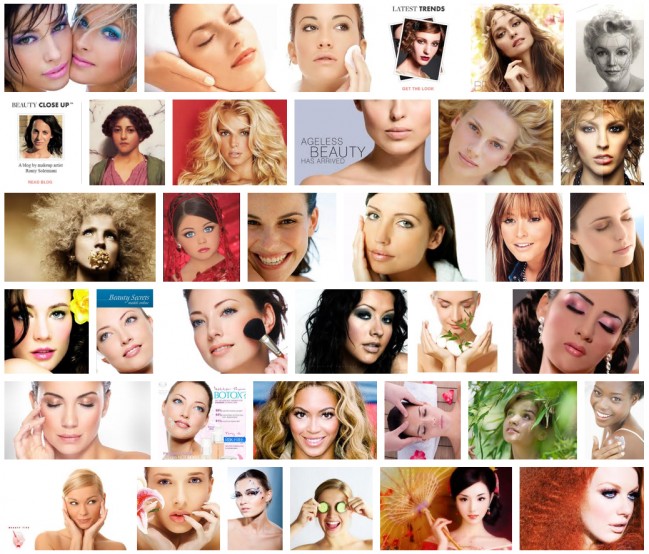

As in all other branches of science, there seem to be fascinating new theories, research and discoveries in neuroscience on a daily, if not hourly, basis. With this in mind, brain and cognitive researchers have recently turned their attentions to the science of art, or more specifically to addressing the question “how does the human brain appreciate art?” Yes, welcome to the world of “neuroaesthetics”. Alexander Edmonds has a thoroughly engrossing piece on the pursuit of “beauty” and the culture of vanity as commodity. And the role of plastic surgeon as both enabler and arbiter comes under a very necessary microscope.

Alexander Edmonds has a thoroughly engrossing piece on the pursuit of “beauty” and the culture of vanity as commodity. And the role of plastic surgeon as both enabler and arbiter comes under a very necessary microscope. But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions:

But what of the “why” of beauty. Why is the perception of beauty socially and cognitively important and why did it evolve? After all, as Jonah Lehrer over at Wired questions: