China, India, Facebook. With its 900 million member-citizens Facebook is the third largest country on the planet, ranked by population. This country has some benefits: no taxes, freedom to join and/or leave, and of course there’s freedom to assemble and a fair degree of free speech.

China, India, Facebook. With its 900 million member-citizens Facebook is the third largest country on the planet, ranked by population. This country has some benefits: no taxes, freedom to join and/or leave, and of course there’s freedom to assemble and a fair degree of free speech.

However, Facebook is no democracy. In fact, its data privacy policies and personal data mining might well put it in the same league as the Stalinist Soviet Union or cold war East Germany.

A fascinating article by Tom Simonite excerpted below sheds light on the data collection and data mining initiatives underway or planned at Facebook.

[div class=attrib]From Technology Review:[end-div]

If Facebook were a country, a conceit that founder Mark Zuckerberg has entertained in public, its 900 million members would make it the third largest in the world.

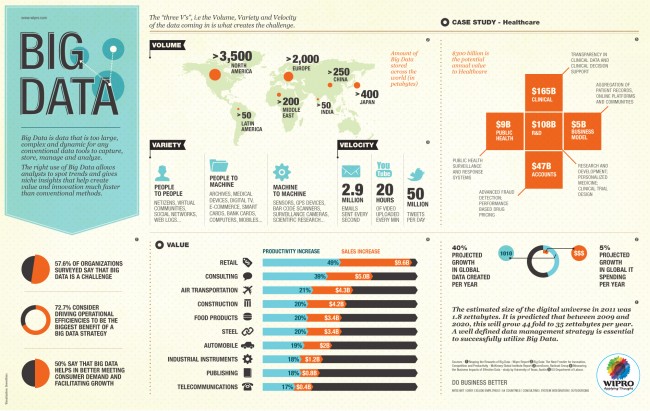

It would far outstrip any regime past or present in how intimately it records the lives of its citizens. Private conversations, family photos, and records of road trips, births, marriages, and deaths all stream into the company’s servers and lodge there. Facebook has collected the most extensive data set ever assembled on human social behavior. Some of your personal information is probably part of it.

And yet, even as Facebook has embedded itself into modern life, it hasn’t actually done that much with what it knows about us. Now that the company has gone public, the pressure to develop new sources of profit (see “The Facebook Fallacy“) is likely to force it to do more with its hoard of information. That stash of data looms like an oversize shadow over what today is a modest online advertising business, worrying privacy-conscious Web users (see “Few Privacy Regulations Inhibit Facebook”) and rivals such as Google. Everyone has a feeling that this unprecedented resource will yield something big, but nobody knows quite what.

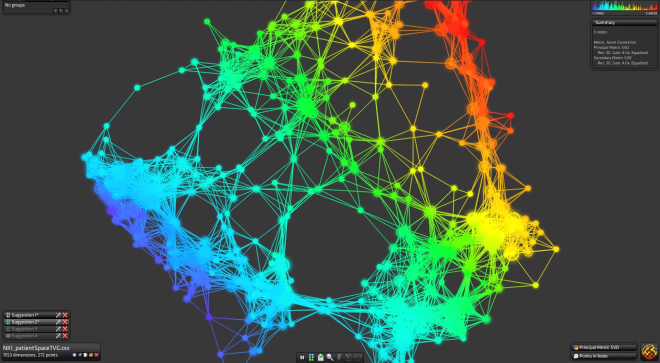

Heading Facebook’s effort to figure out what can be learned from all our data is Cameron Marlow, a tall 35-year-old who until recently sat a few feet away from Zuckerberg. The group Marlow runs has escaped the public attention that dogs Facebook’s founders and the more headline-grabbing features of its business. Known internally as the Data Science Team, it is a kind of Bell Labs for the social-networking age. The group has 12 researchers—but is expected to double in size this year. They apply math, programming skills, and social science to mine our data for insights that they hope will advance Facebook’s business and social science at large. Whereas other analysts at the company focus on information related to specific online activities, Marlow’s team can swim in practically the entire ocean of personal data that Facebook maintains. Of all the people at Facebook, perhaps even including the company’s leaders, these researchers have the best chance of discovering what can really be learned when so much personal information is compiled in one place.

Facebook has all this information because it has found ingenious ways to collect data as people socialize. Users fill out profiles with their age, gender, and e-mail address; some people also give additional details, such as their relationship status and mobile-phone number. A redesign last fall introduced profile pages in the form of time lines that invite people to add historical information such as places they have lived and worked. Messages and photos shared on the site are often tagged with a precise location, and in the last two years Facebook has begun to track activity elsewhere on the Internet, using an addictive invention called the “Like” button. It appears on apps and websites outside Facebook and allows people to indicate with a click that they are interested in a brand, product, or piece of digital content. Since last fall, Facebook has also been able to collect data on users’ online lives beyond its borders automatically: in certain apps or websites, when users listen to a song or read a news article, the information is passed along to Facebook, even if no one clicks “Like.” Within the feature’s first five months, Facebook catalogued more than five billion instances of people listening to songs online. Combine that kind of information with a map of the social connections Facebook’s users make on the site, and you have an incredibly rich record of their lives and interactions.

“This is the first time the world has seen this scale and quality of data about human communication,” Marlow says with a characteristically serious gaze before breaking into a smile at the thought of what he can do with the data. For one thing, Marlow is confident that exploring this resource will revolutionize the scientific understanding of why people behave as they do. His team can also help Facebook influence our social behavior for its own benefit and that of its advertisers. This work may even help Facebook invent entirely new ways to make money.

Contagious Information

Marlow eschews the collegiate programmer style of Zuckerberg and many others at Facebook, wearing a dress shirt with his jeans rather than a hoodie or T-shirt. Meeting me shortly before the company’s initial public offering in May, in a conference room adorned with a six-foot caricature of his boss’s dog spray-painted on its glass wall, he comes across more like a young professor than a student. He might have become one had he not realized early in his career that Web companies would yield the juiciest data about human interactions.

In 2001, undertaking a PhD at MIT’s Media Lab, Marlow created a site called Blogdex that automatically listed the most “contagious” information spreading on weblogs. Although it was just a research project, it soon became so popular that Marlow’s servers crashed. Launched just as blogs were exploding into the popular consciousness and becoming so numerous that Web users felt overwhelmed with information, it prefigured later aggregator sites such as Digg and Reddit. But Marlow didn’t build it just to help Web users track what was popular online. Blogdex was intended as a scientific instrument to uncover the social networks forming on the Web and study how they spread ideas. Marlow went on to Yahoo’s research labs to study online socializing for two years. In 2007 he joined Facebook, which he considers the world’s most powerful instrument for studying human society. “For the first time,” Marlow says, “we have a microscope that not only lets us examine social behavior at a very fine level that we’ve never been able to see before but allows us to run experiments that millions of users are exposed to.”

Marlow’s team works with managers across Facebook to find patterns that they might make use of. For instance, they study how a new feature spreads among the social network’s users. They have helped Facebook identify users you may know but haven’t “friended,” and recognize those you may want to designate mere “acquaintances” in order to make their updates less prominent. Yet the group is an odd fit inside a company where software engineers are rock stars who live by the mantra “Move fast and break things.” Lunch with the data team has the feel of a grad-student gathering at a top school; the typical member of the group joined fresh from a PhD or junior academic position and prefers to talk about advancing social science than about Facebook as a product or company. Several members of the team have training in sociology or social psychology, while others began in computer science and started using it to study human behavior. They are free to use some of their time, and Facebook’s data, to probe the basic patterns and motivations of human behavior and to publish the results in academic journals—much as Bell Labs researchers advanced both AT&T’s technologies and the study of fundamental physics.

It may seem strange that an eight-year-old company without a proven business model bothers to support a team with such an academic bent, but Marlow says it makes sense. “The biggest challenges Facebook has to solve are the same challenges that social science has,” he says. Those challenges include understanding why some ideas or fashions spread from a few individuals to become universal and others don’t, or to what extent a person’s future actions are a product of past communication with friends. Publishing results and collaborating with university researchers will lead to findings that help Facebook improve its products, he adds.

…

Social Engineering

Marlow says his team wants to divine the rules of online social life to understand what’s going on inside Facebook, not to develop ways to manipulate it. “Our goal is not to change the pattern of communication in society,” he says. “Our goal is to understand it so we can adapt our platform to give people the experience that they want.” But some of his team’s work and the attitudes of Facebook’s leaders show that the company is not above using its platform to tweak users’ behavior. Unlike academic social scientists, Facebook’s employees have a short path from an idea to an experiment on hundreds of millions of people.

In April, influenced in part by conversations over dinner with his med-student girlfriend (now his wife), Zuckerberg decided that he should use social influence within Facebook to increase organ donor registrations. Users were given an opportunity to click a box on their Timeline pages to signal that they were registered donors, which triggered a notification to their friends. The new feature started a cascade of social pressure, and organ donor enrollment increased by a factor of 23 across 44 states.

Marlow’s team is in the process of publishing results from the last U.S. midterm election that show another striking example of Facebook’s potential to direct its users’ influence on one another. Since 2008, the company has offered a way for users to signal that they have voted; Facebook promotes that to their friends with a note to say that they should be sure to vote, too. Marlow says that in the 2010 election his group matched voter registration logs with the data to see which of the Facebook users who got nudges actually went to the polls. (He stresses that the researchers worked with cryptographically “anonymized” data and could not match specific users with their voting records.)

This is just the beginning. By learning more about how small changes on Facebook can alter users’ behavior outside the site, the company eventually “could allow others to make use of Facebook in the same way,” says Marlow. If the American Heart Association wanted to encourage healthy eating, for example, it might be able to refer to a playbook of Facebook social engineering. “We want to be a platform that others can use to initiate change,” he says.

Advertisers, too, would be eager to know in greater detail what could make a campaign on Facebook affect people’s actions in the outside world, even though they realize there are limits to how firmly human beings can be steered. “It’s not clear to me that social science will ever be an engineering science in a way that building bridges is,” says Duncan Watts, who works on computational social science at Microsoft’s recently opened New York research lab and previously worked alongside Marlow at Yahoo’s labs. “Nevertheless, if you have enough data, you can make predictions that are better than simply random guessing, and that’s really lucrative.”

[div class=attrib]Read the entire article after the jump.[end-div]

[div class=attrib]Image courtesy of thejournal.ie / abracapocus_pocuscadabra (Flickr).[end-div]

China, India, Facebook. With its 900 million member-citizens Facebook is the third largest country on the planet, ranked by population. This country has some benefits: no taxes, freedom to join and/or leave, and of course there’s freedom to assemble and a fair degree of free speech.

China, India, Facebook. With its 900 million member-citizens Facebook is the third largest country on the planet, ranked by population. This country has some benefits: no taxes, freedom to join and/or leave, and of course there’s freedom to assemble and a fair degree of free speech. Google has been variously praised and derided for its corporate manta, “Don’t Be Evil”. For those who like to believe that Google has good intentions recent events strain these assumptions. The company was found to have been snooping on and collecting data from personal Wi-Fi routers. Is this the case of a lone-wolf or a corporate strategy?

Google has been variously praised and derided for its corporate manta, “Don’t Be Evil”. For those who like to believe that Google has good intentions recent events strain these assumptions. The company was found to have been snooping on and collecting data from personal Wi-Fi routers. Is this the case of a lone-wolf or a corporate strategy? Cities are one of the most remarkable and peculiar inventions of our species. They provide billions in the human family a framework for food, shelter and security. Increasingly, cities are becoming hubs in a vast data network where public officials and citizens mine and leverage vast amounts of information.

Cities are one of the most remarkable and peculiar inventions of our species. They provide billions in the human family a framework for food, shelter and security. Increasingly, cities are becoming hubs in a vast data network where public officials and citizens mine and leverage vast amounts of information.